Don’t call Cage The Elephant a rock band.

Sure, if you look back at the last decade of the rock charts, you’d be hardpressed to find a band that has shown more dominance in the genre. Since the Kentucky six-piece offered up their self-titled debut album in 2008, they’ve topped the Billboard Alternative Songs chart a staggering eight times, with four other songs landing in the top 10. It’s a remarkable run that puts them behind only Red Hot Chili Peppers, Linkin Park, Green Day, and Foo Fighters in the chart’s history for the most No. 1s, and tied with U2.

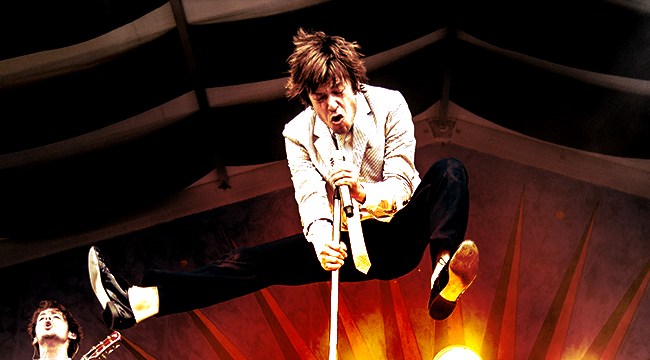

Then there is the band’s revelatory live show, a swaggering presentation that often features the members exploring every corner of the performance space, leaping into the sky with abandon, and plunging into the audience with gusto. No two sets from the troupe are quite the same, with the group seemingly taking its cues from legends like The Rolling Stones, with the kind of charisma that could easily translate to a stadium, even if the band hasn’t quite earned the following yet to put them as headliners in the largest spaces available. But just because the shoe fits, that doesn’t mean it’s necessarily comfortable to wear.

“I don’t really feel tied to any genre specifically,” frontman Matt Shultz frustratedly claims early in our phone conversation when asked about his band’s place in the rock world, clearly bothered by the tendency to reduce the group to its most basic attributes. “That might come across surprising, but I find them incredibly hindering to the creative process.”

On the band’s latest album and their first since winning the Grammy for Best Rock Album for their previous release, 2015’s Tell Me I’m Pretty, Shultz is putting his money where his mouth is. Social Cues undoubtedly has plenty of sturdy guitarwork (the Vapors-sounding “Tokyo Smoke,” the fuzzed-out groove of “Dance Dance), moments of post-punk flair (the anthemic album opener “Broken Boy,” the attitude-driven single “House Of Glass“), and more than a couple emotionally-charged ballads (the tender and spare “Love’s The Only Way,” the lush album-closing “Goodbye“), but more than ever, the band’s varying tastes have crept into the fold. Look no further than their collab with Beck, “Night Running,” for forays into dub and hip-hop that sound something like an updated Specials for the 21st century, or the gentle orchestration of “What I’m Becoming” that places the band into the sort of timeless territory that many artists fail to ever achieve. Every album from the band is equal parts reinvention and refinement, and Social Cues finds Cage The Elephant more confident than ever in that formula, not relying on the tricks that got them to this point, but moving bravely into the unknown.

Social Cues is also the most personal album of the band’s career, taking root lyrically in the dissolution of Shultz’s marriage. References to the relationship’s end can be found throughout, often directly in songs like “Goodbye” and their current chart-topping track “Ready To Let Go.” The personal toll that it took for Shultz to record the album has been well-documented, with his bandmates (guitarist brother Brad Shultz, drummer Jared Champion, bassist Daniel Tichenor, guitarist Nick Bockrath, and keyboardist Matthan Minster) offering both emotional support and a platform to exorcize his demons. In our conversation, which has been edited and condensed for clarity and length, Shultz expands on the pain that fed into the album’s creation and the joy that comes out of the artistic process.

Anyone that’s listened to your music or seen you perform can witness the roots that you guys have in these classic rock traditions. It feels rarer and rarer. A contemporary like Arctic Monkeys turned away from that a bit on their last album, or Greta Van Fleet is endlessly knocked for their rock influences. Do you feel like you are on an island as a band at this point, keeping this spirit alive with very few peers?

We think of things on much more of a song-to-song basis, and much more on a character level. But definitely, we try to pull away from anything that is persona-based, and I mean rooted in rock stardom or rock and roll or hip-hop or any of those words you might associate with a genre. We’re more focusing on the specifics, like the communitive properties of songwriting. So, we don’t really think of it that way.

These days, we look at it as playing the studio. It’s an extremely diverse medium. We’re really excited to see how things are going to grow. It’s funny and kind of sad really that people have equated a musical group and hinged it to the words “rock and roll,” and forgot the versatility of several instrumentalists composing together. You don’t have to be tied down to those confines. I’m just really excited with all the new software that’s emerging, all the new technology and instruments, and the ideas of approach. We’re just really excited about where things are moving.

With that in mind, do you think you’re generally disinterested with what is going on around you in the commercial music sphere. Are you not really paying attention?

It’s like peripheral vision. You pay attention to things as they come into your sphere of interest or as they come into your awareness. One of the artists I’ve always looked up to is David Bowie. The thing I always thought was so incredible was that he was entrenched in the avant-garde mediums and styles, but was very aware of what was happening in contemporary culture. Not to take yourself out of the current world, that would be weird and counterintuitive. It would be forced…

It’s strange that you asked this question about rock and roll. It brings up all these emotions inside myself. I think of the segregation of music, and if you really want to go back to the beginnings of what rock and roll was and hip-hop, segregation of gender and race and everything that’s disgusting in this world. I think that music and art is the last place — and not that segregation should exist anywhere — but there shouldn’t be any kind of segregation in genre or anything.

Not to say that I think these things, these are observations. But as listeners and as a culture, we’ve moved so far beyond them, even to the point where I think you and I, we can understand this topic without talking about it much. And yet, we keep living out this weird narrative where we keep forcing ourselves to talk about it because it is comfortable. And I think that when you get down to it, why people feel obligated to or to keep going back to what’s comfortable to them is because we’re so afraid of things we don’t know or what we’re not familiar with. Maybe if we go a little more with our instincts, it would be a lot easier for us to reimagine our current reality.

Even if people didn’t know in advance how personal this album is for you, it’s pretty apparent on first listen. “Ready To Let Go,” “The War Is Over,” and “Goodbye” are all pretty explicit about the ending of things. How hard was it for you to confront such heartbreaking topics with this clarity, especially while you were still in the midst of it?

Confronting the topics wasn’t really the difficult part. It was just that we were making a record during an extremely difficult season in life. So, hopefully, if you want to get to that place of honesty, you’re going to be dealing with those kinds of things. There were moments where maybe it was too raw, and that was sort of difficult. But for the most part, life was already turbulent enough, life was presenting its own difficulties so I didn’t have to focus on that part.

I feel like a lot of people take time off to process things like that as they are happening. Did you consider doing something like that and take a break from the creative process, to live with your pain for a little while before turning it into art?

No, the way that it happened, I was kind of forced to naturally. With everything that was going on with us and with John [Hill, the album’s producer], the sessions were broken up into three or four major sessions, which were anywhere from two weeks to a month long. There were sometimes a couple of months between each session. So each time, there was plenty of time to reflect, which often was tortuous, to be honest. There were times when it was too much. For “Goodbye,” we did one take and then I kind of just left and left for two weeks. The band was really understanding, though.

That’s good that the band is on board with what you need to function as a person.

The thing is, my relationship falling apart is the juicy story, so that’s where everyone leads. But there’s some pretty heavy stuff that’s also really understandable. My cousin had passed away with my best friend growing up. I had two seriously close friends commit suicide. So, they totally understood where I was at.

I feel like people often forget about that in the workplace, that you have to exist as a human outside of being a worker. But in the creative fields, it can be even more difficult, because the job is in your mind.

Sometimes these really heavy things, it’s viewed as plasticizing your life. It presents it as theater, so it might not be understood that these things come from really heavy experiences. But it’s good that the band was really graceful.

Are you worried about having to spend so much time with these songs with your upcoming touring?

No, thankfully there’s been an extreme amount of healing since then. And it’s such impulse-base work, rooted in improv and reaction. There’s so much there, that I think there’s going to be a lot of joy in performing it.

You’ve spoken in some interviews about watching documentaries about murderers and seeing yourself in these disturbing figures, and that comes across a little in the lyrics, too. Some people could take that the wrong way and see this as violent music. What’s the distinction you draw there between this sort of empathy without actually condoning the behavior?

A lot of these people who’ve committed hideous crimes are extremely relatable in conversation. They victimize themselves and explain their point of view, and to a certain degree, especially with like cult leaders, when you just get a little information, you can see their perspective. But then you dig into the details and you see that they are really off and have made some pretty terrible decisions. But I could relate to these people at face value. And I thought it was really interesting that we could present ourselves in this way of kindness that is relatable and likable and sometimes lovable, and inwardly be a monster. And how does that monstrosity manifest itself in each of our lives in different ways. Some people murder people.

I’m not saying everyone’s a murderer or whatever. But I’m saying that I could relate to that feeling of being a monster inwardly. I thought that was an interesting duality that you could present yourself as kind, and still be a monster. Or that you could be kind or be monstrous outwardly and see yourself as a monster inwardly, but kind of in a cannibalistic way emotionally, where maybe you didn’t understand how valuable you were and in some ways were destroying yourself. It was just a lot to play with.

I feel like that could scare some people. I feel like people want to distance themselves from thinking like that.

Are you speaking for you personally?

Maybe!?

Before we end, I did want to say something. At first listen, it’s easy to catch the grief and mourning and notes of pain. But for me when I listen to it, I hear an incredible amount of joy and hope, and I really hope that comes across. Whenever you are in a deep time of mourning, it doesn’t negate the time of uplift.

Social Cues is out 4/19 via RCA Records. Get it here.