It is such a damn shame that De La Soul and Tommy Boy Records couldn’t seem to resolve their interminable royalties dispute in time for the 30th anniversary of 3 Feet High And Rising, not only because it means that the planned release of the trio’s catalog to streaming services has been delayed — including their aforementioned groundbreaking debut — but also because it means that, rather than celebrating a game-changing album, much more of the group’s time has been spent fighting for fairer treatment from the label that originally brought them to the world’s attention.

30 years ago, there wasn’t a “rap game” — at least, not as we know it now — so it could hardly be said that 3 Feet High And Rising changed something that didn’t exist yet. Instead, De La Soul’s funky, witty, genre-bucking debut expanded the boundaries of what exactly rap could be. At a time when militance, stoicism, and street-smart, tough guy demeanor stood at the forefront of the burgeoning culture’s mainstream representation, three jazz-rap “hippies” — Posdnuos, Trugoy, and Maseo — ushered in a “D.A.I.S.Y. Age” that demonstrated a whole new paradigm for rap — much of it, at the cost of the group’s “street credibility.”

It takes a lot to go against the grain. It might take even more to do so when the grain hasn’t quite settled yet, when it seems like the whole world is trying to push in one direction. In 1989, rap was in flux. Just one year before, a plethora of groundbreaking albums dropped from artists and groups as diverse as the artists themselves, from Doug E. Fresh and the Get Fresh Crew and DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince, to MC Lyte and Salt-N-Pepa, to Public Enemy and NWA. However, as wildly divergent as the sounds and styles were, there seemed to be a common consensus that hip-hop and rap music as its offshoot were meant to be rugged, tougher than leather, maybe even downright gangsta — even Will Smith and Jeff Townes as The Fresh Prince and DJ Jazzy Jeff positioned themselves in opposition to the idea that rappers needed to be stone-faced, ice-cold roughnecks.

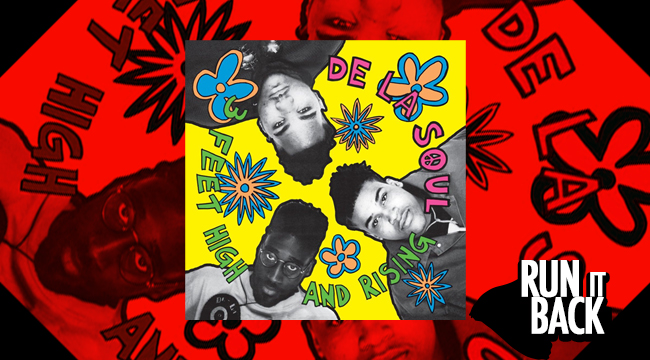

In 1989, De La Soul didn’t so much challenge that conception of rap music so much as they ignored it almost entirely, crafting an alternative sound almost wholesale from a stack of records as tall as their producer for the album, Prince Paul, and as colorful as its flower-printed cover, designed by British art collective the Grey Organisation. Where the beats on other classics of the era hit like bricks with punishing kick drums and bruising bass lines, 3 Feet High And Rising contained soundscapes with varied layers and textures that they swung around like wiffle bats, connecting in a vastly different way. Rather than sampling just from jazz, funk, and soul, they borrowed as heavily from Hall & Oates and Steely Dan for more melodic, almost relaxing soundbeds from which to sling their quirky but no less sharp lyrics about self-love (“Me Myself and I”) and adolescent whimsy as on “Jenifa Taught Me (Derwin’s Revenge).”

The skits that pepper the album are downright goofy at times, the sampling and sonic experimentation as off-kilter as anything attempted today. If I may be so bold with my metaphors, De La were the Soundcloud rappers of their day, completely ignoring rap’s few established rules of decorum in favor of a freewheeling, intensely personal style. They weren’t making records for mass appeal; while many of their peers and forebears would often make that declaration, it was clear that De La was more willing than any to stand behind it. Yet, their songs did find appeal outside of their tight-knit circle of associated artists (the Native Tongues collective, consisting at the time of De La Soul, The Jungle Brothers, A Tribe Called Quest, Queen Latifah, and Monie Love), spawning a spate of Billboard rap singles chart hits, including the anti-drug diatribe “Say No Go,” the defiant anti-biting not-quite-battle-rap track “Potholes In My Lawn,” and of course, the Native Tongues-introducing posse cut, “Buddy.” However, the longest lasting and most impactful of their singles was the almost house-ish self-determination of “Me, Myself, And I,” which not only topped the US R&B and US Club Play charts, but has also made recurrent appearances throughout pop culture, from television to movies to video games.

Ironically, breaking the then malleable rules of mainstream rap helped to lay the groundwork for a new subset of rules for what would come to be known as “alternative rap,” with a focus on personal narratives, social commentary, and experimental beat work. Their stylistic heirs can be counted from across the modern landscape of hip-hop, from the colorful, rebellious wave of cloud rappers splashing out South Florida’s sun-dappled beaches to the furrowed brow navel-gazing of intellectuals like J. Cole and his Dreamville cohorts. Take a listen to “Jenifa Taught Me” and “Wet Dreamz” back-to-back and try to deny the parallels — it’s impossible because they’re self-evident. De La Soul’s DNA presents itself throughout hip-hop, even in the work of those artists who may not necessarily know who the Plugs — as they dubbed themselves on 3 Feet, a theme they’ve continued to use ever since — are.

That’s why it’s such a damn shame that their game-creating/solidifying/re-casting debut can’t be streamed today. They were so ahead of their time, there are still insights to glean. 3 Feet High is so important, rap rebels of today should have it to validate their viewpoints, whether that’s bucking prevalent trends, or simply to remind stodgy old heads that this music can be fun, weird, experimental, quirky, and different. The Plugs are still tunin’ to this day thanks to tours and festivals which have kept them relevant even without a readily available back catalog to draw recognition (and royalties) from, but we should be able to go back and see where they started to be able to fully appreciate how far they’ve come. They helped made it okay to be yourself in hip-hop, even when that self is a hippie-dippy kid from Long Island with a proclivity for picking flowers. Their legacy, however, lives on, even if they moved on from their colorful beginnings; a D.A.I.S.Y. age by any other name, is still hip-hop to the core, with the power to challenge the status quo and change the game.

De La Soul is a Warner Music artist. Uproxx is an independent subsidiary of Warner Music Group.