When you get a call like that it doesn’t seem real. You don’t know how to react because it feels like a practical joke and you’re waiting for the “Gotcha!” moment at the end when you both burst into laughter.

“Nicole got shot. It doesn’t look good.”

My sister couldn’t possibly be calling me to tell me my youngest sister had been shot, right? There’s no way this was real.

Except it was.

Nicole was in dire straits after being shot under shady circumstances. She’d remained conscious long enough to knock on a neighbor’s door and ask for help, then later told the responding paramedics what had happened. After that, Nicole went unconscious, her heart stopped and she had to be revived, several times. She’d gone too long without oxygen to her brain and it was decided there wasn’t much that could be done. After several heart-wrenching days of watching machines keep her alive, we made the decision to shut them off and accept her fate, as a family.

Nicole was less than three months away from her 20th birthday.

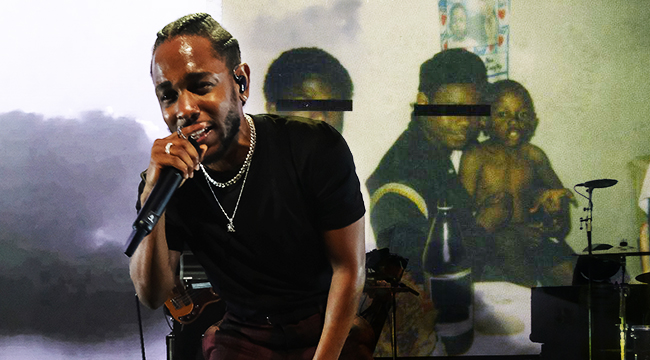

Kendrick Lamar makes songs about people like Nicole.

Kendrick structured Good Kid M.A.A.D City like a film, with scenes playing out in skits and on records, creating a narrative of a day gone awry. It was essentially Boyz N The Hood the album. Kendrick is the Good Kid, finding a way to survive in a mad city, an avatar for so many that have come before him and lived through that exact existence in neighborhoods where the question “Where you from?” comes with deadly consequences.

For over an hour Kendrick told the story of every Good Kid who answered that faithful question with some variation of “I don’t bang,” or some other verbiage that explains that they aren’t looking for trouble. Kendrick is affiliated, by friendship, by family, by his geographical location but he’s not as knee deep in the life surrounding him as his friends. He explains it all succinctly with one half bar.

“I’m like Tre, that’s Cuba Gooding.”

Tre is, of course, the main character in Boyz N The Hood, who ultimately decides to opt out of a fateful ride to get revenge for his friend who had been killed hours earlier. Tre is the outlier, the teenager in South Central headed to college, the one brave enough to ask out of the car, brave enough to go against the grain and try to stay on the straight and narrow.

For decades, rap has been the celebration of Tre’s friends, those brave enough to fully entrench themselves in a lifestyle that Tre so desperately tried to avoid. Those who get asked where they’re from and boisterously reply “straight outta Compton,” unafraid of the consequences. Gradually, the genre has expanded to include more perspectives of the black and brown existence in America, and those stories are as varied as any other cultures, even when funneled into the same neighborhoods and cities that become riddled by the same violence and trauma.

Telling stories is what Kendrick does, both his own and the stories of those people he’s come into contact with throughout his life. Those stories have left him a tortured soul, and it seems his only release is to retell them in his chosen medium. It’s on one of M.A.A.D City‘s final tracks, “Sing About Me” that he comes to grip with the idea that sharing those stories is painful to those who lived through them.

Here he’s confronted with two perspectives, both times by relatives of those whose stories he’s told on tracks. The first is, again, practically ripped straight from Boyz N The Hood, when the brother of Kendrick’s friend Dave — who was killed earlier in the album — comes to him for peace of mind and for the chance to think out loud. It’s a therapy session that few in that situation are ever actually afforded, as the trauma of killing his brother’s killer has enlightened him to the error in his ways.

It mirrors that final scene in Boyz, where Doughboy — played by Ice Cube — has similar revelations. “In actuality, it’s a trip how we trip off of colors,” Dave’s brother wonders aloud at one point to Kendrick, before admitting just seconds later “This Piru shit been in me forever, so forever I’ma push it, wherever, whenever.” It’s a vicious cycle, and it continues moments later when he’s killed before he can even finish what he has to say to Kendrick.

The second is a little more unfamiliar, especially in a genre where women are often objectified as sexual conquests or receptacles of male desire only included as accessories to the protagonistic diamond-studded characters at the center of most rap songs. Here, Kendrick is confronted by the sister of Keisha, a woman he immortalized on Section 80 by telling the story of her life as a prostitute. There, Kendrick humanized Keisha on “Keisha’s Song (Her Pain),” and sympathized with her, wondering how to rescue her from the path she’s taken.

Keisha’s sister has walked down a similar path, but wants none of Kendrick’s sympathy, and explains what Kendrick couldn’t explain on his track — “this is the life of another girl damaged by the system,” she says, detailing to Kendrick that it’s not a life she chose so much as she was tossed into it with little choice or knowledge of how to get out of it. The story mirrors the gangbanger’s from the first verse, painting Keisha’s sister as a victim of circumstance, not some misguided girl who simply chose a bad path. In telling these stories, and explaining how they reached these points, Kendrick humanizes characters that often aren’t given that privilege.

When Kendrick raps these people’s stories, what he’s really discussing is their trauma; the trauma of having lived through these terrible events — and having done so for generations — so much so that black and brown people have become desensitized to death, violence, racism, oppression, sexual abuse and any other number of traumas.

In doing so, Kendrick gives a voice to the voiceless and humanizes the demonized, and that empathy also trickles down to those closest to the humanized demons. Some may take it as disrespect, others will appreciate it, but it’s vital to those people that these stories are told, and Kendrick has taken it upon himself to be the one to tell them.

For all of Kendrick’s many talents, this is his most extraordinary ability, and the most significant. His ability, and willingness, to tell not only his story, but the untold stories of those around him, and add nuance to their characters that are seldom seen, and never heard or told is what makes Kendrick special and Good Kid M.A.A.D City a classic. It gives his music an unmeasurable weight that very few artists — if any — can match. It’s what makes “Sing About Me” the greatest song of his lauded career, it’s what makes Good Kid his finest hour and it’s what makes him the single most impactful and essential voice in this era of rap music.

This is what makes his music resonate, not only with the Good Kids in the mad cities everywhere, but also to the Keishas, and to the those who have been swallowed whole by the streets and continue down their paths, even when they see the error in their ways like Dave’s brother did. Kendrick speaks to every end of the spectrum and speaks for them as well. He tells each and every story and he doesn’t expose, he explains. He doesn’t vilify these people, he empathizes with them.

Still, Keisha’s sister didn’t take too kindly to having her sister’s past judged on that platform, and understandably so. But Dave’s brother, in all his clarity in the light of an unspeakable trauma, appreciated the gesture and saw that it came from a place of love.

Nicole’s brother? Well, it’s a little complicated.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BWN7T2AlvgS/?taken-by=banskygonzalez

The week of Nicole’s funeral I had a dream, and though you’re supposed to forget your dreams the moment you wake up I doubt I’ll ever forget this one. I was at an amusement park and watched Nicole get on a rollercoaster. But after a few minutes, I noticed something was terribly wrong. The ride was broken, and unbeknownst to her, Nicole was barreling towards a disaster. I could see the problem, and with some superhuman effort I could probably prevent the tragedy, but for whatever reason, I never moved, and eventually, I woke up right before the roller coaster could crash.

I was riddled with guilt, and my subconscious would not let me forget it. There was probably something I should have done to help Nicole, but I never did it. I watched as she went down the wrong path, never stepped in to reroute her and because of that, as the big brother, I felt responsible for her death. I thought if I had taken care of her, Nicole could have been so many things, but I didn’t and there she was, dead at 19 under unclear, horrifying circumstances. It was my fault, and my mind was reminding me of that, even in my sleep.

She was shot in a room full of what she believed to be her friends, but after some foul play with a gun, her boyfriend’s 16-year-old brother shot her, either by accident or on purpose, depending on what story you believe. Eventually, Nicole’s killer was found guilty and sentenced to 18 years in prison without the possibility of parole, ironically one year less than Nicole had actually lived herself. Justice was served, I suppose.

These stories don’t always end neatly, in fact, they often end abruptly and agonizingly, just like on “Sing About Me.” But for those who live through them, sometimes hearing them told from a voice as powerful as Kendrick’s can be cathartic. The day after Nicole’s funeral “Sing About Me” came on and I cried, louder, longer and more painfully than at any point since that initial phone call. It was overwhelming and I simply could not control myself. It took almost a half an hour to regain my composure and finish driving to my destination. Somehow when it was over, and all the tears were wiped from my face I felt better, not entirely, but better than I had in weeks.

Three years later, whenever I hear “Sing About Me,” I smile, and feel the warmth I used to get whenever Nicole came into my life again, however briefly, with her brashness and unrelenting optimism despite whatever was going on in our lives. She was loud and uncensored but full of love no matter what life threw at her. Now, the song always reminds me of that girl, the one behind the woman who took a few wrong turns in life and ended up in the wrong place at the wrong time, with the wrong crowd and had her own life cut abruptly short. Nicole was — is — still Nicole, no matter where life took her.

At one point on “Sing About Me,” Dave’s brother says to Kendrick “I wonder if I’ll ever discover a passion like you and recover the life that I knew / as a youngin in pajamas and dun-ta-duns.” Often, I find my mind wandering back to that time in my life as well, especially when I think of Nicole. I loved Nicole for the woman she was, but I think of that girl more often, full of innocence and so curious about life. That’s where the warmth she had came from, and that’s the warmth I always remember in those random moments when she crosses my mind. “Sing About Me” reminds me of all of the parts of her that made her whole, her flaws, her innocence, her past and, yes, her abrupt, untimely and brutally tragic passing.

So even if Kendrick’s music can be traumatic to listen to at times, sometimes it takes revisiting that trauma, told by the single most poignant and salient voice in this generation of rap, to make me feel whole again. Sometimes, that trauma is the only thing that can remind me of that warmth my sister had. Kendrick decided to sing about those characters that others forgot or simply chose to ignore. He sings about us, about me, about Nicole. No matter how many years pass, his album will continue to give a voice to the voiceless — and while it’s well understood at this point that it’s a classic, that extra layer of resonance may make it something even greater than that.

On the chorus of “Sing About Me,” he asks, begs even, that we sing about him so his legacy lives on when his light shuts off. Because he took the time to sing about all of us, he can rest assured that we’ll be singing about him forever, just like he asked.

[protected-iframe id=”d00003c24a554729f1be757d39b127c6-60970621-76566046″ info=”https://open.spotify.com/embed?uri=spotify:album:6PBZN8cbwkqm1ERj2BGXJ1″ width=”650″ height=”380″ frameborder=”0″]