I co-founded Rawkus Records in the mid-90s, at the tail end of what is referred to as the “Golden Age of Hip-Hop.” Emcees were huge figures who were almost superhero-like. In fact, their names often sounded like superheroes (or supervillains) — think Method Man, Red Man, Big Punisher… Having a larger-than-life persona with a name that matched was a prerequisite for a record deal or to make a buzz in the industry.

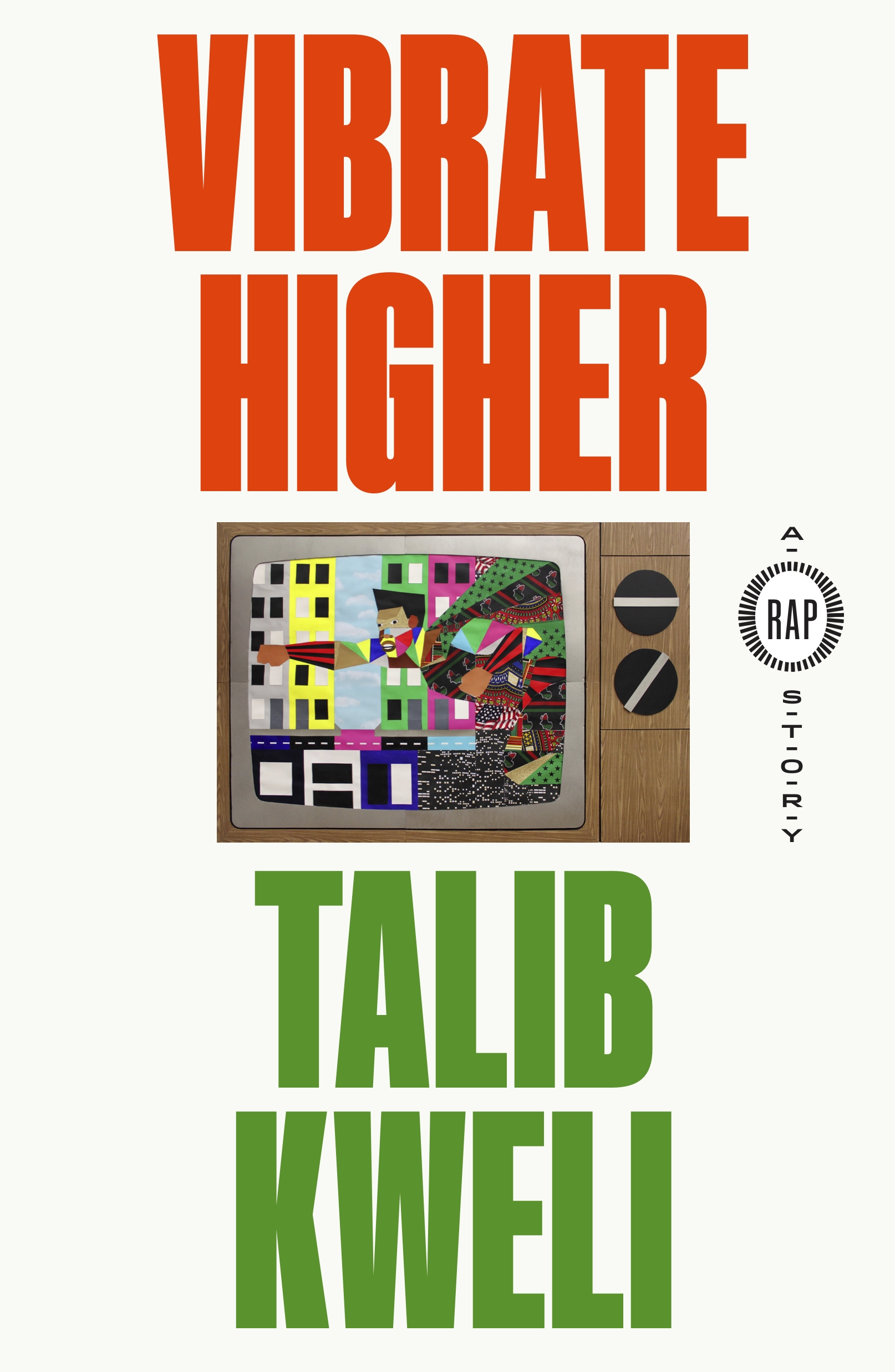

It was in this climate that I met Talib Kweli, a Brooklyn rapper who used his given name and made music that echoed the Brooklyn he grew up in — full of literary references, big spiritual ideas, and Black revolutionary politics. Our relationship began with the single “Fortified Live” and grew to include albums from Black Star, Reflection Eternal, and Kweli as a solo artist. Every album a classic.

During that stretch, we had a lot of fun, but we also had serious arguments and disagreements — as an artist and label head often do. Through it all, we stayed friends — something far rarer. I am forever tied to the legacy of Rawkus and I thank my friend Talib Kweli for allowing me to see its meaning both through his People’s Party podcast, which we collaborate on, and now through his book Vibrate Higher: A Rap Story.

***

Kweli, I want to tell you that your book is incredible. And I’ve been recommending it and sending it to friends and hip-hop fans. But beyond that, it reminds me of books that I love that really are guidebooks for how to live a curious and creative life. And in many ways, it’s a book about putting yourself in life situations that really open yourself up to your full potential. How much of that was your goal?

I did not realize that you could also put my book in the self-help section.

I mean I think you can put any — I recommend great books about musicians to anyone who’s trying to improve their lives because I think it’s about reaching your creative potential.

Yeah, I agree. I think that was a byproduct — an unintentional-but-great byproduct — of writing this book. That wasn’t my intention. I mean certainly, it’s my intention to inspire people to live their dreams and be their best selves. That’s every creative, optimistic person’s intention. But my intention really was more selfish than that. I wanted to tell my story. And I don’t know, maybe “selfish” is not the right word, because if it was just about telling my story, there wouldn’t be any other stuff except for “so this happened” then “that happened” and “next, this happened.” It was very intentional for me to add social commentary, add context.

The most intentional thing I did was really get the backstories behind Park Slope, behind my parents and my grandparents, behind Dilla, Madlib, people like that. I was very intentional about making sure that my story was the story of everyone who helped me live this life.

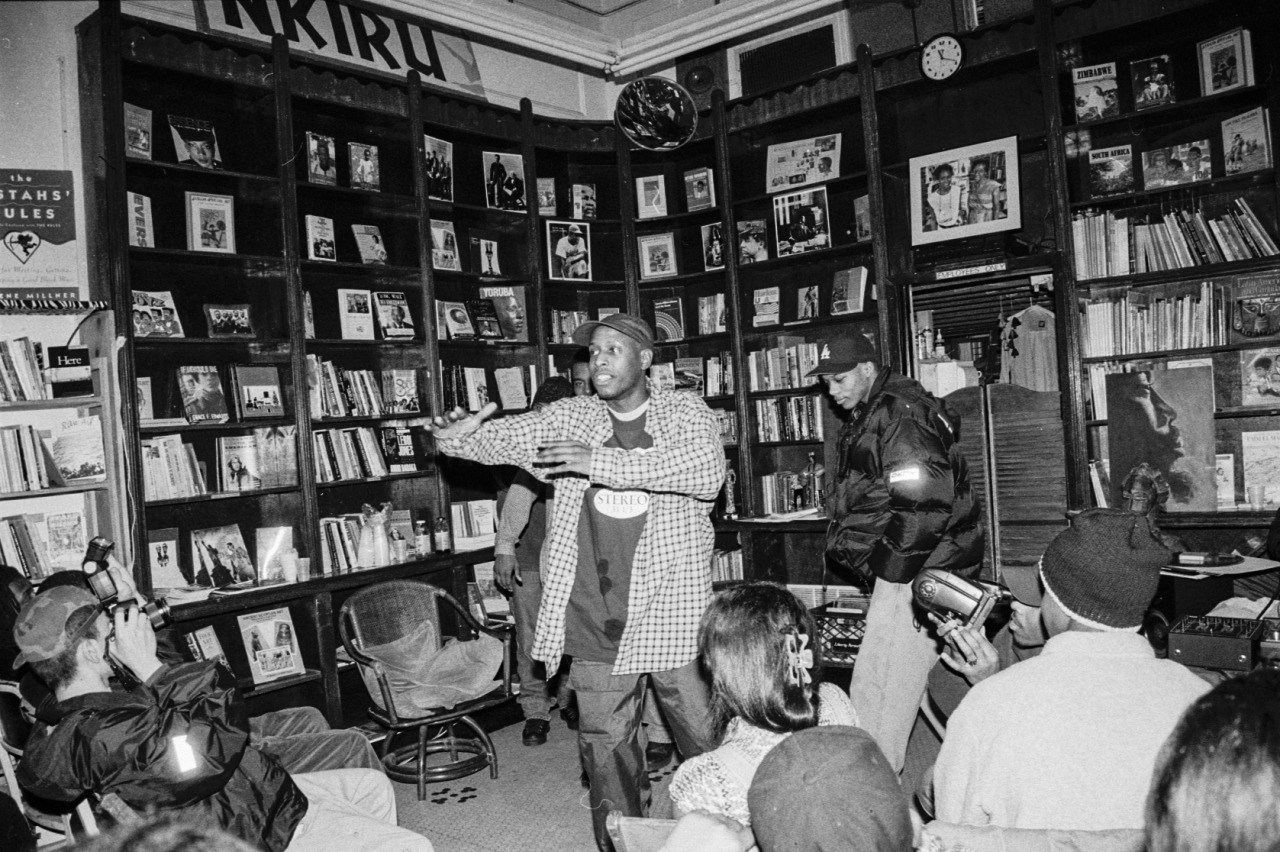

Talib Kweli performs at Nkiru Books, in Brooklyn.

I think when it comes to rap stories, we all know the story of the street-hustler-turned-rap-star — the Jay-Zs, the Biggies, 50 — but the story that you just described a moment ago, it’s your unique story, but I feel like you’re also making a case, just like Kanye had a new story to tell, that there’s room in hip-hop for multiple types of stories.

I think you nailed it. And that’s why I called it Vibrate Higher: A Rap Story. Because it’s definitely a story about hip-hop, it’s a story about rap, but it starts off talking about how nerdy I am, and that’s very much on purpose. It’s saying, “Look, hip-hop is so beautiful, rap is so beautiful and diverse and big that it has room for all of these stories.” And often there are so many hip-hop fans that are either voyeuristic or just academically understand a 50 cent or a Lil Durk. Either you’re voyeuristic and you’re fetishizing it or you understand that it’s pain and circumstance and poverty that creates artists that make that type of music. But either way, there are many, many rap fans who are black. Regardless of race, but particularly when you talk about how people fetishize the trauma of the hood, they’re talking about black kids, they’re not really talking about Eight Mile when they say that. And so when you’re talking about that, there’s a lot of black kids who are poor and live in the ‘hood but don’t have that experience.

There’s a lot of black kids who are not poor, don’t live in the hood, but still love hip-hop. And I’m definitely someone, I come from educators. I don’t come from rich people. One of the worst stereotypes out there is something that is often lobbed at me and my family is that somehow if your people are educated that you’re automatically rich. And so that’s something that I wanted to really … I didn’t address that directly, but I think it’s implied in the book that “Look, I come from educators. I come from people who are not thugs or tough guys or gangsters, but this is still a very black experience and this is still a very working-class experience of people who didn’t have nothing.”

You said it’s Vibrate Higher: A Rap Story, and I think the “rap story” part is really clear. But let’s talk about vibrating for a moment. The book is also a bit of an instructional guide and a definition of the vibe, the power of the vibe. So why is it important for a regular person — not a rap star, not a musician — for someone to understand the power of the vibe?

You said my story’s unique, right? Well, my unique rap story is the idea of raising up… it’s centered around raising consciousness. And without even realizing it, as I perused through the book myself, I say more often than I intended to how much hip-hop for me reminded me of the black liberation art movement, and how much I was connected to consciousness, and how it was such a focus. I didn’t realize until reading back in the book how much that was my focus. And then reading some of the reviews. Reading some of the reviews, people picked up on that. That’s what made me read back through the book, people picked up on the fact of “Okay, this has really been a singular focus.”

That’s really what I thought hip-hop was about. When I was at junior high school, at my most impressionable, the best rappers were KRS-One, Brother J, Rakim, and Chuck D. And so I was like, “Well, to be the best this is what you have to do. You have to raise the consciousness.” And that’s what “Vibrate Higher” is all about, raising the consciousness. As far as what we would call a regular person, because I don’t think anybody’s regular … Well, actually there have to be some regular people, but that’s not who we’re dealing with out here. We’re dealing with exceptional people. The thing that we all have to do is curate our own playlist and be conscious consumers. We can’t demand that artists be conscious when we are not living up to those same standards. I need to be as conscious as you are and you need to be as conscious as I am if we’re having this conversation about consciousness.

It’s rewarding — you feel it as a human being — when you touch some level of vibration. And you sense subconsciously when you’ve done something to raise it, I think.

Yeah, I mean you’re right in that there’s a reward to it. There are endorphins. Helping people out, and raising the consciousness, and adding to knowledge, and gaining knowledge, and all that stuff feels good. And I think whatever spirituality you believe in, whatever science you believe in, it makes sense that it would feel good. It makes sense that compassion would feel good. I am of the belief that the human being’s number one job in the world is to gain and spread knowledge, and we should spend our entire lives trying to do that. And that’s really why we’re here … because that’s how we elevate the whole consciousness of a people. And we come from this earth, so people are connected to the earth.

We raise the consciousness of people, we save the earth.

I’m going to skip to something that you just reminded me of that I think a sub-theme in the book is, and I’ve seen this firsthand: you have a close relationship with MCs who have a traditional religious practice. And I got a sense as a reader, it was interesting for me to reflect on your relationships and read about them, I sensed that there’s a part of you that might even be envious of how having a religious practice can help elevate that vibe and elevate that creativity. Is that something that you think about?

That question strikes at the heart of my spiritual journey of music. “Envious,” I think, would be the wrong word, but I definitely appreciate how having a spiritual discipline gives one focus, particularly Islam. That’s why I have so many Muslim friends, I think. Also, my parents gave me a Muslim name, so I attract Muslims — but I’ve never been a Muslim. I was raised Christian and I gave that up, so I don’t consider myself ascribed to any particular religion. But a lot of the practices of Islam — the mechanics of it — are a great container for receiving information, I think. And I appreciate that. I really appreciate that discipline. I really appreciate the discipline, being in a group with Yasiin Bey, and seeing how attempting to be a good Muslim has made him a better person, to me has been awe-inspiring.

I really appreciate people that take that journey. I think everything isn’t for everybody, and I think that I can achieve a lot without ascribing to a certain religion. People — because I’m able to see what’s the good in certain practices — some people claim me sometimes. They’ll be like, “You Muslim. You Christian.” I don’t have a problem with that. It’s like the way I see the world online, I recognize the bad parts. I’m not taking on the dogma or any of the mythologies of the stories, all the parables, I’m not talking about any of that. I’m just talking about the compassion. That stuff, if any of that stuff aligns with your principles, then so be it.

Talib Kweli and Yasiin Bey backstage before a Black Star concert.

I found the parts in the book when you talked about religious MCs to be really interesting. And it was interesting that your musical diet was from a lot of MCs who embraced a traditional religious practice and yet you did not. And then you also partnered with one.

Yasiin [Bey, formerly Mos Def] gave me a book. I can tell you… Oh, Jesus, I forgot the name of this book, but I’ve referenced it in my lyrics. What’s the name of the book? Anyway, there’s a lot about the way Muslim scholars and Islamic scholars break down certain things, I think it’s very beautiful and masterful. And I think the way that the people who I think really, really try to live with the principles, not the fringe, because the fringe of anything is always an issue. Extremists of any religion, it’s always… But the people in particularly amongst my Muslim friends, the ones who try to live according to however they swore to live, I’ve seen them do some fantastic and beautiful things.

I’m going to go from my really deep, thoughtful question about the book, to my less deep question about the book. So, I’ve heard Method Man talk about taking shrooms in the nineties, and you had a pretty lengthy shroom scene in your book. So, what we all want to know is: were shrooms a much bigger part of nineties hip-hop for artists than we think?

My guess would be that shrooms were a privilege. It was like how coke was before crack. I would guess that that’s true because my first shroom experiences were at boarding school. I went to boarding school with rich white kids. And then while I was on tour with rappers.

Were other rappers taking shrooms?

I don’t want to blow nobody up, but I got it from other… No. It wasn’t “most” people, it wasn’t most of the rappers I was around, just a select few. I think shrooms have got more popular over the years. I think shrooms, at this point, most people I know who smoke weed also at least microdose.

Yeah. In general, hip-hop has become more psychedelic over the years.

I agree.

But in the nineties, I feel like that level of psychedelia just wasn’t really present.

I feel like you had to be touring with rappers. Or you had to be either touring with rappers or around white kids, to be honest with you. I don’t recall anybody in Brooklyn at that point really being onto shrooms. Now everybody’s on shrooms.

That actually leads me to my next question. You mention touring with rappers and being around white kids — Your book reminds me a lot of the Beastie Boys book, which you actually did a segment of the audiobook for.

Yeah. I toured with the Beastie Boys and did the audiobook for the Beastie Boys, it all connects.

And I think the underlying part of the Beastie Boys book, to me, was they had this amazing ability to always put themselves in the right situation. It’s like they truly willed themselves by just always wanting to be out and finding “the cool thing.” I noticed in Vibrate Higher that you would refer often to amazing situations as divine inspiration. But how much do you actually attribute that to divine inspiration versus luck, or actually just the result of all the hard work that you put into putting yourself into the right situation?

Mrs. Miller, Mrs. Adelaide Miller, who owned the bookstore, Nkiru Books… She was a member of a church called the Unitarian Church, and above the door of the Nkiru, she had a sticker. It was like a little poster. I guess it would be a meme nowadays, but it was a little sticker and it said, I’m paraphrasing here but it said, “The only hands God has to work with are these.” And then it was a picture of some hands, some human hands. That always stuck with me, because it was like, “If you truly… I guess that he said the Bible is… I don’t know if this is from the Bible — “faith is nothing without works.” If you’re sitting there on your knees, praying like, “God, please help me, please help me,” that’s not how divine inspiration works. It works when you get up and get out and get involved and do the work. And then when you do that work, the universe… When you put that work out there, the universe returns the love and the favors.

And I want to be clear because I don’t want people to think I’m preaching like some old slave time religion, like, “Oh, you’re supposed to work all through today and then you get your just desserts in heaven.” No. We’re supposed to get our just desserts right now. You’ve still got to fight for every dollar you earn, and you’ve still got to fight for your respect and all that. But the way in which I make things happen is it all connects with everything. It all connects with me being influenced by the Five-Percent Nation, as well. The way that I make things happen is by making them happen. And it’s because God is the son of man. I mean, Christians say Jesus is the son of man and of God. That’s because they’re saying God is man, and man is God. It’s like the song from the twins, gospel singers, where they’re like, “I see the God in you.”

That’s what I tell people all the time. I see the God in you. It all comes from you. We all have the potential, the power, to do it. The first place you got to look for God is to look inside yourself. It’s all the same thing.

Making your own destiny. That’s the Beastie-Kweli connection, in my mind.

They were outside of the culture in ways that I could never imagine being. Back then, it was a lot more “down by law” culture. If you just were participating in hip-hop, hip-hop was always very welcoming. Hip-hop was always very welcoming to people of all races, creeds, and colors, and wherever you’re from. Just so long as you kept it real, and you were down, you were just pure about your interests.

And the Beastie Boys were definitely that. They were definitely respected and embraced by the community, but they definitely came from outside of the community. And me, coming from where I was coming from at the time, at the time hip-hop wasn’t as big as it is now. And it was largely an inner-city thing of people who were living in poorer neighborhoods. My proximity to hip-hop was, to me, in some ways, probably similar to the Beastie Boys’ proximity to hip-hop. I was an outsider, to a degree. And so the way in which I approached it was… it wasn’t about being a voyeur and it wasn’t about being a tourist. And it wasn’t about no Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness shit.

But it was definitely like “Yo, for me to participate in this culture and be authentic with it. Well, goddamn, I got to do all of it. I got to see everything. I got to read the back of every album cover. I got to go to every party off of every flyer in all of hip-hop.” I was the kid on the train that kids would get on the train and look at me like, “Yo, yo, you like hip-hop?” I’m like, “Yeah.” And then they would give me a mixtape or give me a flyer for something and I would listen or go to the show.

You talk a lot about privilege. One of the things in the book that I really love was the privilege of having great friends. And JuJu, Rubix and [John] Forté — I also had the privilege of knowing them. I mean, what they brought to your life is so incredible.

It really is. And it can’t be quantified.

I mean, I would say, if I didn’t know your friends and I read that book, I’d be very jealous. I would think, “God, I wish I had friends like that.” Go get some friends, people.

I know they’re great friends because I wrote about them in that way. But just hearing you say it in that way, after having read the book and it’s all written down, it makes me even more like, “Wow, you’re right. I have some fucking great friends.”

One of the moments that was special in both of our lives that you referred to as it seemed like divine inspiration was when Mos [Yasiin Bey] said, “Hey, I have a name for this group [Black Star].” It was funny recalling that moment because I remember it so well. And I suppose we could attribute a lot of things to that moment, but you both put so much work into developing your careers. I had put work into trying to build a label, but I suppose it could have been divine.

Yeah, I think so. And if the stars align we’re in the right place at the right time, I think all that is divine. I think… I mean, is there a science that we can break down that could tell us why this happened?

I don’t know.

And I love science.

I mean, I suppose it’s all random in the scheme of the universe, but yeah.

It just sounds divine to me. It sounds divinely inspired.

I agree. So, speaking of Black Star, I think another theme that I really enjoyed in his book and that I paid a lot of attention to, was your view of collaboration, but not just collaboration, the art of compromise. I really enjoyed the parts where you talked about building an album with Hi-Tek and how you had different approaches, how Yasiin had different approaches to doing business. I even enjoyed the parts where you talked about navigating your life with execs and managers. I would say from a reader’s point of view, abstracting myself for a moment, that it seemed like you had a really positive experience when it came to collaboration and compromise. Do you feel that way?

I do. For me personally, I wouldn’t be who I am without that. I didn’t have the confidence or the sort of… maybe it’s just the confidence to even do things on my own, by myself. I was working with Hi-Tek and working with Yasiin and working… learning from and working… learning from them, working with them. It’s just to me, what makes me dope is the stew. The stew in which I participated in when I went to Washington Square Park. When I went to the Lyricist Lounge, rhyming alongside Wordsworth and Punchline and AI Skills and Jean Grae and Supernatural and John Forte and all that, without that, this doesn’t happen. When you look at the jazz cats, they were already releasing multiple albums a year — all just collaborating. And that was sort of the spirit in which we did Black Star.

But I will say as a reader Kweli, it didn’t seem that it was obvious to you at first. It seemed that you had to learn to collaborate with Hi-Tek. You had to learn —

I didn’t have to learn that it was necessary to collaborate, I had to learn how to do it. I knew that it made sense to be in a group with Hi-Tek. I knew that that was the right thing to do. I knew it was the right thing to be in a group with Yasiin Bey. But in terms of how I created art, I had to learn and how I communicated as just as an adult human person, that’s what it’s more about. I think that goes for anything. Just working in a cubicle next to somebody you don’t agree with all the time. But I do want to stress, even on my solo albums, I enjoy making sure that people get credited properly. I enjoy saying this was… writing and talking about the people I collaborate with. I really… even when it’s just my name on the cover it’s still a huge collaboration.

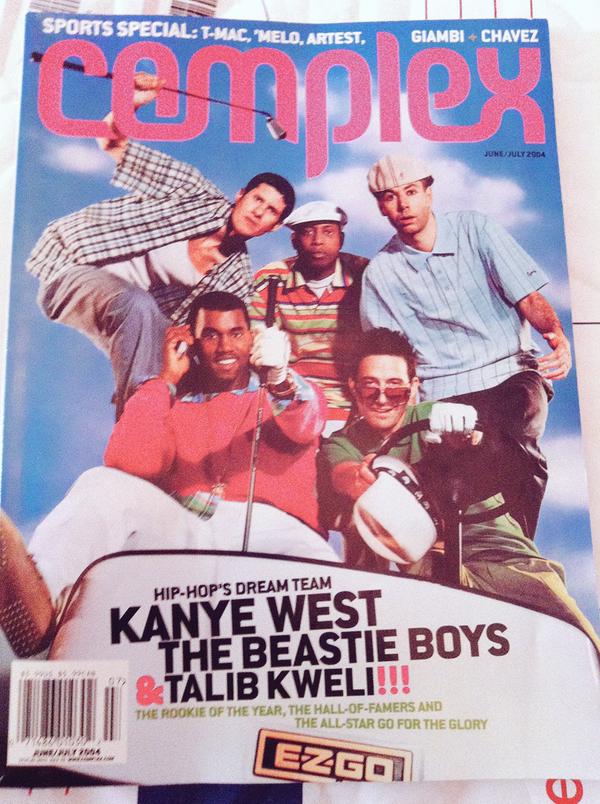

Talib Kweli and Yasiin Bey with actor Michael Rapaport.

I’ve always sensed that from you, a hundred percent. Let me ask you this question. One of the things that when people ask me for advice on how to be the next Talib Kweli or the next Yasiin Bey or the next Pharoahe Monch or whatever, I always say that really it’s about the right blend of audacity and execution. I really liked your Kanye chapter because I think you did a really good job of illustrating that concept, that he had incredible audacity, and yet he had all the execution in the world to back that up. For an artist to be successful, if you had to just pick one, either audacity or execution, what do you think is more important?

I think execution.

Didn’t think you were going to say that.

Really?

Yeah. I kind of thought based on how you were so impressed by Kanye’s audacity…

Well, I know a lot of audacious ass mother fuckers but they have terrible execution.

Right. Me too.

I find myself saying that a lot. The audacity.

Where do you place yourself when it comes to the balance of audacity and execution?

I think I place myself squarely in between Madlib and Jay-Z.

I love that answer. That’s a great answer. One of the things I got from the book too, was this… you mentioned the word blue-collar when we first started talking. And I think that really comes through — this sense that there’s a certain level of pride in being a blue-collar musician touring on the grind. It comes with things, it comes with some negatives and some things that were hard for you and maybe some life regrets, but a lot of pride in being a working-class MC. What do you want readers of your book to take away from the concept of being a working-class MC or blue-collar MC?

I want people to understand that me using my real name is deliberate and me… the way in which I carry myself, the way in which I dressed, the way in which… even the fact that, for better or for worse, the way I engage on social media. The fact that I’m one of the only people who is, I’m going to talk to you regardless. If you say something nice to me, I’m going to be nice. If you say something not nice to me, I’m going to not be nice. And whether or not people agree with that or not, it definitely comes from a real, in my mind, working-class ethic.

That I am not separate from the people. I’m right here with you.

With the people.

And if we need to be on the front line, then I’m going to be on the front line. And it’s also just a shout-out to all the other MCs I see on the road, to El Da Sensei, to Jeru the Damaja, to Big Krit, to David Banner, you know what I’m saying? To people who are looked at as icons or people who have contributed greatly to the craft. And I’m out here on the road and I see these people working. And I know what it is, but it’s like, I know what life they’re living. And I know that because we have all at one point in our lives, been on television or been in a movie or been on something, that people think that once you walk through that door, that forever you have no bills. That you always going to have money. Just because you have achieved a degree of celebrity. And it’s definitely not that. Just because you’ve seen me on TV a couple of times, just because Kanye or Jay Z said my name, does not mean all my bills are paid. And especially for someone who’s doing conscious music. I made a choice to do music that has been, traditionally, not profitable.

I made this choice because making money was never “the thing.” I don’t make music to make money. But I do perform music to make a living. And as I get older and become a more man, I’ve learned how to diversify a bit. And to the point where I don’t depend on selling rap records to make money. If I had to depend on that, my kids would starve. But rap, hip-hop has been good to me, it’s been very good to me and the fans have been good to me. And so many people have related to what I said, supporting my vision, that I’m very blessed to live a life that’s a lot more comfortable than most people.

Just a moment ago, you were talking about different MCs that you want to show respect to. And I think the book, in so many ways, was a love letter to MCs. And a thank you to MCs. And when I think about the origins of People’s Party and the reason I knew it would be an instant success, is because of the passion that you have and the respect that you have for MCs.

It reminds me of how Seinfeld feels about comedians.

Wow, that’s heavy praise. I love and respect how Seinfeld feels about comedians.

Do you see that comparison?

I do. I think that’s very accurate and… Yeah, I think that’s very accurate. When I first did a song with The Roots, I was on “Double Trouble” and I was taken off. And a couple of years later, I was asked to be on the same Roots album twice [“Phrenology,” 2002]. When I first developed a relationship with Black Thought, I already kind of knew Questlove a little bit. But I didn’t know Black Thought like that. And it was just me and him in a studio. And he told me, he was like, “Yeah, I heard that verse. I didn’t know who you were. I didn’t know anything about Black Star. I was just like, “Yo, I don’t think that verse works for this song.” But then he was like, “Then I paid attention to you.” And he said, “All these other MCs have all this other stuff going on. Everyone wants to have an endorsement deal or movie or whatever it is and you were just focused on MCing.” And he said, “That’s why I want to do music with you. Because I only MC for other MCs.”

I’ll never forget him saying that. It struck me.

So besides the advice of, “Read my book” — but I really would advise people to read this — what are some words of wisdom that you have for aspiring creators, artists, and entrepreneurs?

Write it down.

Their life story?

Write it down, tell your story. If you don’t want to write a book, do a podcast about your life. If you don’t want to do that, make a graphic novel or comic book. Do something, write it down.

And focus more on execution than audacity.

I’m not going to give that advice. You’re asking me if I had to choose. I don’t want to, I don’t think anyone has to choose.

Okay. Fair enough. So here’s my final question, so that we don’t have the longest print interview in history. So I want to say that there are accomplishments that are not even in your book. There are accomplishments that I know about. There are accomplishments that you’ve had recently. The accomplishments in your book are enough to be beyond impressive. And really adding it all up is very crazy. And you should be very proud of yourself. I’m very proud to be your friend.

Thank you, I’m proud to be your friend as well.

Thank you, man. With all of that, is there anything else that you want to do? And do any of those creative goals involve another Black Star album?

There’s plenty I want to do. I mean, if you notice, the last chapter of the book was called the beginning. That’s because I’m just getting started and there’s definitely a Black Star album, definitely produced by Madlib. It’s definitely closer to seeing the light of day than it’s ever been before. That’s where we’re at.

So you’re not just flying around on private jets with Madlib, you’re actually finishing this record?

I mean, we have to get around to get the album done right.

Does Madlib travel any other way besides private jet and Rolls Royce?

I’m not going to subject Madlib to airports during a lockdown, Jarret. Madlib is a national Goddamn treasure.