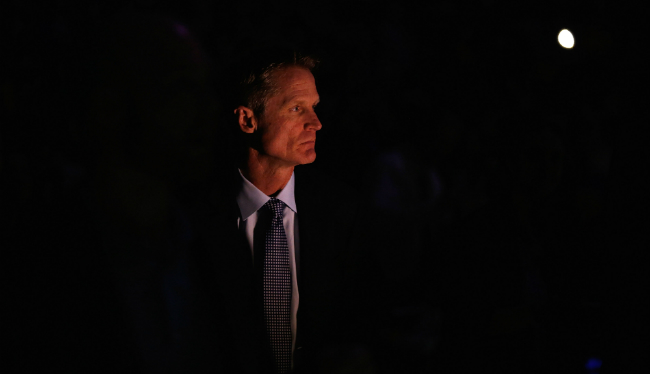

The 2015-16 Warriors rewrote history by concluding their record-breaking NBA regular season with an astonishing 73 wins. Golden State may have achieved basketball immortality, but it faced many challenges along the way, including playing without Steve Kerr, the 2016 NBA Coach of the Year, for half of the season.

In an exclusive March interview with Kerr this year, he called this “the hardest year of my life.” Six weeks after the Warriors won it all last June, and following a 40-year championship drought in the Bay, Kerr underwent back surgery. Unexpected medical complications were the result. He was forced to take a four-month leave of absence to recover, leaving his team in the hands of assistant coach Luke Walton.

This was not Steve Kerr’s first challenge. He has experienced many extremes along the spectrum of emotions throughout his life. He won five NBA championships playing alongside Michael Jordan and Phil Jackson in Chicago, and with Tim Duncan and Gregg Popovich in San Antonio. However, during his freshman year at Arizona, he received a call from Beirut notifying him of his father’s assassination by an Islamic Jihad during the Lebanese Civil War.

Steve and his father, Malcolm, were both born in Beirut, Lebanon. Malcolm, a Princeton graduate, lived in Lebanon and the U.S. while continuing to further his education. His life’s ambition was to return to Lebanon and lead the American University of Beirut (AUB), a dream realized in 1982 when he became its president. For over a year, Malcolm Kerr worked out of his office in College Hall, just outside of which he was killed on January 18, 1984.

“His murder made me understand the pain that others experience,” Kerr says. “It’s made me realize that millions of people go through these things.”

While Malcolm Kerr’s assassination has been well chronicled, the lesser-known story of his parents’ involvement in the first major American humanitarian effort initiated his family’s relationship with the Middle East.

* * *

The Kerrs were on the frontline of American relief after World War I. Stanley Kerr arrived in Aleppo in 1919 and began photographing, documenting, and rescuing Armenian women and orphans. He then transferred to Marash to take charge of an American mission. His memoir, The Lions of Marash, is set at this location and describes how the armies of Mustafa Kemal eradicated the Armenians from the new Turkish republic.

Private American charity reached the Armenians first. In response to the massacre of over 1.5 million Armenians, philanthropist Cleveland Dodge formed the Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief. Former president Theodore Roosevelt advocated intervention, saying, “All Americans worthy of the name feel their deepest indignation aroused by the dreadful Armenian atrocities[a].”

* * *

Ann Kerr is the coordinator of the Fulbright program at UCLA, where her husband Malcolm taught for 20 years as chairman of the Department of Political Science. A copy of her eldest son John’s Fulbright I.D. hangs in her office alongside the newspaper showing Steve Kerr’s 1997 NBA championship-clinching shot. Today, John Kerr serves on the board of the Near East Foundation, continuing the family legacy of involvement with the region.

During my meeting with Ann Kerr, she says Steve has his father’s self-deprecating sense of humor, most evident during his tenure as an analyst for NBA on TNT, while also possessing his passion and calm demeanor. Steve travelled the world with his parents, and gained many experiences overseas that shaped his world view.

As a junior at Occidental College, Ann left to study abroad in Lebanon. Three days a week, she taught at a Catholic Armenian girls’ school — the Immaculate Conception. She met Malcolm at AUB while he completed his Master’s, and they were soon married in Santa Monica in 1956. Today, Ann continues her work with Fulbright to engage the Middle East with American higher education.

* * *

On February 10, 1920, the French garrison at Marash withdrew abruptly, and thus abandoned more than 20,000 Armenians to the marauding insurgents of Mustafa Kemal. The Turks threw kerosene-doused rags on Armenian homes, and churches were put to flame. Sickened missionaries like Stanley Kerr could only observe helplessly through binoculars[b].

The “Marash Affair” gave rise to an irreversible tide that swept Kemal to power; for the Armenians of Cilicia, it marked the onset of a new round of devastation and the final exodus from their ancestral homeland into permanent exile.

* * *

Unlike Armenians in Beirut, Steve Kerr was not raised on stories of genocide, but he was aware of his forefather’s humanity in the face of atrocity. “I was aware of my grandparents running an orphanage in Marash and eventually finding Beirut through their travels,” Kerr says. “I have a great deal of pride in knowing how much they helped.”

Susan van de Ven, the daughter of Ann and Malcolm, has an exchange of letters with her grandparents about their experiences, which she used for her thesis at Oberlin College, and later presented at the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem in 1986 for the anniversary of the Armenian Genocide. Her grandmother, Elsa Reckman, volunteered as a schoolteacher in Constantinople, and later met Stanley Kerr while working in Marash.

Elsa and Stanley ran an orphanage for Armenian children in Lebanon in the 1920s after leaving Marash until an outbreak of typhoid forced the orphanage to close. Elsa lost an unborn child when she contracted typhoid. They eventually married in Beirut in 1922, and Stanley became the chairman of the Department of Biochemistry at AUB, while Elsa served as dean of women. Following 40 years of faculty service, they retired in 1965.

* * *

The American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, later known as the Near East Relief, is credited with helping preserve the Armenians in the face of the genocide that sought to destroy them. They pioneered the idea that all Americans, regardless of age, income or background, could help others.

The Near East Relief campaign raised a staggering $19.5 million from private donations by 1919, and $117 million by 1930 — over $1.6 billion today when adjusted for inflation[c].

Despite the monumental efforts of the Near East Relief, the Armenian Genocide is not recognized by the United States.

“Everybody learns about the Jewish Holocaust, but very few know about the Armenian Genocide,” Kerr says solemnly. “It’s not taught in schools, and obviously there are still the political issues of whether Turkey is willing to use the word ‘genocide.’”

* * *

After Game 3 of the first round of the 2015 NBA Playoffs last April, Dr. Douglas Kerr, Malcolm’s younger brother, gave a presentation in Cleveland entitled “Witnessing the Genocide,” based on Stanley’s book. In May, after Game 2 of the Western Conference Finals, several members of the Kerr family received a posthumous award in Washington, D.C. on behalf of Elsa and Stanley during a national commemoration of the centennial of the genocide.

In 1965, Antranig Chalabian uncovered a box at AUB containing Stanley’s copies of The New York Times, which eventually inspired Stanley to write his memoir. “Lots of Armenian names in my family history,” Kerr says before retelling when family friend, Vahe Simonian, called him and broke the news of his father’s assassination.

“We’ve had so many Armenians at our house over the years. I felt like an honorary member of the Armenian community through my family.”

* * *

[a] “Roosevelt Heaps Blame on America” New York Times 1 Dec. 1915

[b] Hovannisian, Richard G. “The Postwar Contest for Cilicia and the ‘Marash Affair’” in Armenian Cilicia, eds. Richard G. Hovannisian and Simon Payaslian. UCLA Armenian History and Culture Series, 7. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2008, p. 509.

[c]James L. Barton, The Story of Near East Relief, 1915-1930: An Interpretation (New York; Macmillan Co., 1930), pp. 409-411