It’s a widely held belief on both sides of the political spectrum that the robots are coming for our jobs. Trump’s former Labor secretary nominee, Andy Puzder, argued that rising wages would inevitably force companies to buy robots, not hire people, something we disagreed with. Still, there’s no denying that robots have an effect — but a new study raises a few questions about what that effect is, precisely.

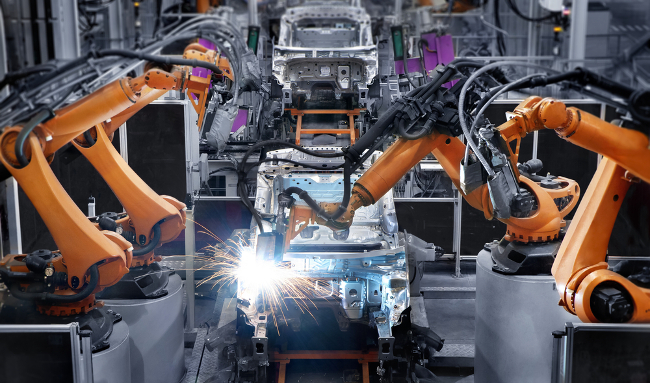

Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo studied the spread of robots between 1990 and 2007 and found some fairly worrying results. They defined robots as automatically controlled, possible to reprogram, and able to do more than one job. In other words, it’s not a robot that enhances productivity, but a robot that replaces a human worker, and usually more than one human. They then tracked the results on local areas over that seventeen year span. They estimate that each robot reduced the workforce by 5.6 workers and potentially drive down wages by as much as 0.5% over time, although they note that these numbers, while not implausible, are a bit high.

Still, that’s arresting, but then why are we seeing all these headlines about strong job reports? The most recent employment report has employment at 4.7%, pretty close to “full employment,” or all labor resources being used in the most efficient way possible. Of course, that’s a number under dispute, but the fairly liberal Economic Policy Institute estimates that February saw 1,590,000 “missing workers”, defined as people who could work but can’t find a job, and adjusts the unemployment rate to 5.6% based on that number. And, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, if you don’t consider temp workers and the underemployed (i.e. people who want to work full time but can only get part time work) full employed, the total rate is roughly 9.6%.

So, what’s going on? Obviously, 10% of Americans who want to work full time, but can’t, for whatever reason, is bad, but it also somewhat contradicts the idea that the robots are going to take all the jobs away from us. The answer is that the jobs most at risk are “routine” jobs, jobs where you follow a set of rules, or repeat the same task over and over again. Those are easy for robots to understand, so they’re the easiest to automate. That may be the reason that all the job growth between 2000 and 2014 came from “non-routine” jobs that required human interaction, thinking on your feet, and other tasks robots are terrible at.

It’s not like these are all great jobs (or super high paying), by the way — Customer service is a “non-routine” job, for example. Furthermore, “easy job” is a relative term. Just ask the engineers behind the robot security guard that ran over a child, or the robot vacuum that accidentally sucked up its owners hair. Robots are very good at handling one task over and over again but when they have to improvise, or circumstances stray from a narrow set of ideal conditions, things go south, quick, so some “routine” jobs likely won’t be threatened for awhile yet.

While robots are also attempting to take white collar jobs, it’s telling that the most successful lawyerbots don’t try criminal cases, but rather handle relatively simple tasks like contesting parking tickets. And, interestingly, robots being good at routine jobs may create more non-routine jobs for humans: Starbucks’ app, which is basically an order robot, is so popular it drove demand through the roof, meaning Starbucks has to hire more humans to make coffee.

(via Gizmodo)