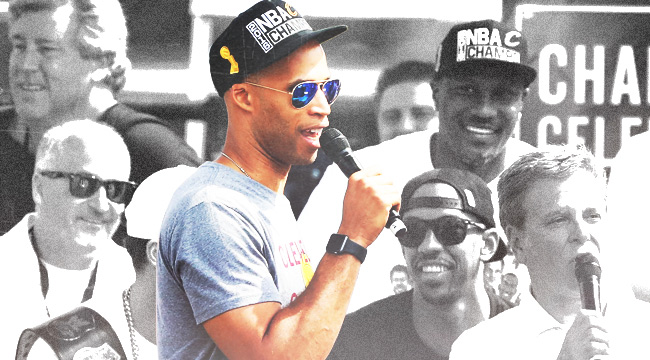

The look was all over Richard Jefferson’s face in the Cavaliers’ locker room after winning the title in June. It wasn’t just happiness, though there definitely was plenty of that. It was relief. Peace of mind, at long last. Hat playfully askew on his head, a beaming smile on his face, Jefferson told a reporter, “I’m retiring.”

It would have been tough to blame him, considering he was two days away from his 36th birthday and had spent the better part of a half decade bouncing from team to team, in search of a squad good enough to bring him the ring that had eluded him. It had been so close – so early in his career – back with Jason Kidd and the New Jersey Nets at the start of the 21st century. After coming full circle, you would have understood if Jefferson had walked away.

But here he is, still with the Cavaliers, still smiling after a win against the 76ers in December. Though he’s not without his regrets.

“Have you seen my shooting percentage?” asks Jefferson, laughing. “I should have retired.”

Jefferson’s scenario is a familiar one. As NBA players age, they tend to gain more control over their location as their skills and physical gifts diminish. Some choose to sign with teams who will give them a big role or more money, and some choose to find the best team they can, the one closest to the title, even if it means being a bit player and/or taking a smaller contract.

David West, for example, took an $11 million pay cut to join the Spurs last year, where he helped them to one of the best regular seasons in NBA history, only to fall short again, slightly closer to where his Indiana Pacers peaked. Now, he’s making the veteran minimum for Golden State, seemingly one step closer to getting his first title at age 36, averaging a career-low 11 minutes per game. And that’s probably how he wants it.

The Cavs added even more veterans for their stretch run in hopes of repeating and winning the arms race against the Golden State Warriors, who made their big move in signing Kevin Durant back in July. With Durant on the shelf for the next few weeks, Cleveland played the buyout game, with Deron Williams and Andrew Bogut choosing the Cavs for a variety of reasons, most notably the opportunity to play with LeBron James. But the chance at extra hardware certainly didn’t hurt.

“The way I explain, is that there has never been to this day someone who asked me how many points I scored, how many rebounds I grabbed,” says Shane Battier, who won titles with LeBron in 2012 and 2013 and now works as director of basketball development and analytics for the Heat. “They ask me, where do you keep your rings and which one do you decide to wear? Stats, they’re great and all, but the closer you get to the end, you realize that stats don’t matter.”

For guys like Jason Kidd and Gary Payton, it took a career and the acceptance of a smaller, different role from their All-Star peaks to get a ring just at the end of their career. For guys like Tracy McGrady, who hung on the end of the bench for the San Antonio Spurs’ 2013 playoff run but missed the title in subsequent years, no amount of ego subjugation could overcome the uncooperative fates.

That’s where Mike Dunleavy might find himself now. He found himself traded from the Chicago Bulls, whose core crumbled under injuries, to the title-winning Cavaliers in the offseason, and thought he had his chance to chase that ring, before he was sent to Atlanta for Kyle Korver (another vet in search of a title). Before the move, Dunleavy was asked if he would be more likely to retire after winning a title at this point.

“No question,” Dunleavy said in December. “That’s not to say that if I win a title, I’d just hang it up, but I’d be more inclined to keep playing until I do get one.”

Like McGrady in April of 2013, now Dunleavy has to hope the Hawks get hot – or some contender has an extra roster spot open up – before he calls it quits. For anyone good and fortunate enough to stay in the league as long as he or Richard Jefferson have, it’s natural to be concerned about your legacy.

“I had scored my points and made my money [when I joined the Heat], so the only thing that mattered was winning,” says Battier. “That’s where Mike is now.”

But just as the lack of the big win can drive players to keep coming back, it can also be the thing that keeps you around. Just ask Jefferson, who re-signed with Cleveland even after his joyous farewell.

“Honestly, I love these guys,” said Jefferson. “This is, if not the number one, then top two team I’ve ever been on when it comes to camaraderie. When you combine that with being one of the best teams in the league, and winning a championship, it’s tough to go out on that type of note when you feel like you have an opportunity to do it again.”

The question of legacy, of what a player’s career means to himself, isn’t always answered so easily with a championship. It’s human nature to set new goals as soon as you meet the old ones, like Jefferson has.

“And at the end of the day, part of the reason I didn’t retire is that I wanted to experience going in as the defending champions,” Jefferson said. “You want to go in and experience getting your ring on opening night and seeing the banner go up. There’s a lot of stuff that comes with that, that I didn’t want to miss out on. Getting the opportunity to win the championship twice, to win back-to-back championships? Having that on your resume if you try to continue down on your path in basketball or anywhere in sports, is something that you can’t beat. And, I’m still playing. I’m still contributing.”

Ultimately, it’s important to remember that in among the easy narratives of “going out on top,” the guys who some of us call ring chasers are merely fulfilling the competitive drive that affects every athlete differently. That doesn’t magically vanish with the ring.

“You’ve gotta love what you do, and those guys that kind of check out a little early, they lose that love of the game or other things become a part of their life,” Dunleavy says. “And when you get to the point where you’re doing well financially, you can say, ‘I’m good, I’ve had enough.’ From my standpoint, basketball’s all I know, it’s what I love, and I’m going to do it for as long as I can, as long as my body holds up, and as long as a team wants me.”