Any attempt to narrow down Martin Scorsese’s career to even 15 essential films means losing whole chapters of the Scorsese story. For starters, since the beginning of his career, Scorsese has had an off-and-on sideline — lately more on than off — directing documentaries. This year alone saw the release of the remarkable, truth-bending Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story. Related, Scorsese has another sideline in concert films that dates back to his time as an assistant director of Woodstock and most notably includes The Last Waltz, called in these pages the “best Thanksgiving movie ever made.”

Which brings up another issue: Making cuts is hard. The Last Waltz, one of the greatest concert movies ever made, didn’t make this list. Neither did The Color of Money or Cape Fear or Kundun or Silence or several other movies that would be among any other director’s best movies. But it’s worth noting that some of the films that did make the cut come from late in Scorsese’s career. Some directors say what they have to say then find creative ways to repeat themselves, and there’s really nothing wrong with that. Scorsese, on the other hand, remains restless, as evidenced by The Irishman, his most recent release (which you’ll find quite high on the list). One other matter: Scorsese tends to be a bit harder to rank than other directors. A handful of films tower over others, but that has as much to do with their importance to the history of film in general as their quality relative to his other movies. That said, let’s press on with the 15 greatest from one of the greats.

15. Shutter Island (2010)

Scorsese has never made a horror film, but this psychological thriller starring Leonardo DiCaprio as a troubled U.S. Marshall investigating a mystery at an insane asylum in the 1950s comes close. Darkness-shrouded images and distressing 20th-century classical music set the mood for a twisty story that might border on the ridiculous in others’ hands. Instead, it serves as a prime example of why DiCaprio became Scorsese’s leading man of choice in the second half of his career, bearing the burden of a man carrying unspeakable horrors in his heart trying to make sense of a world that reflects only chaos and awfulness back to him.

14. Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974)

Where Scorsese’s breakthrough film, Mean Streets, saw him revisiting old New York haunts that confused men he grew up around, his follow-up found him wandering well outside his comfort zone. Ellen Burstyn stars as Alice, a woman who finds her life upended after the death of her husband. Deciding to pursue her dreams of becoming a singer, she instead finds herself living a financially precarious existence as a waitress in Arizona. Keying off of Burstyn’s great performance, Scorsese captures the vulnerability of a woman suddenly forced to fend for herself and dangers that range from abusive men to a creeping sense of despair.

13. Casino (1995)

Sometimes dismissed as a lesser Goodfellas, Casino brings the same journalistic detail to a story about the mob and the changing face of Las Vegas starring Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci, and Sharon Stone. But the film has a rhythm and energy all its own and De Niro’s understated work as “Ace” Rothstein, a cautious man unsettled by conditions he can’t control — be it in the casino or his marriage — ranks among his best performances. If there’s a standout, however, it’s Stone. Too often asked to repeat herself in the roles she took after Basic Instinct, here she gets to dig beneath the surface of a character as complex and self-destructive as any Scorsese protagonist.

12. Bringing Out the Dead (1999)

What happens when you spend day after day (and night after night) staring at death and pondering the ugliest possibilities of human behavior? For Frank Pierce (Nicolas Cage, in one of his best performances) it means living always on the verge of cracking. An ambulance driver haunted by the lives he can’t save, Frank threatens to fall into despair as he responds to one tumultuous situation after another in a city that also seems to be falling apart. Patricia Arquette co-stars as Mary, the daughter of a patient who grapples with addiction as her father’s condition worsens. Scripted by Paul Schrader, it’s one of Scorsese’s most overlooked films and makes a fascinating, guardedly hopeful bookend to a previous collaboration, Taxi Driver.

11. The Departed (2006)

An adaptation of the Hong Kong crime drama Infernal Affairs, The Departed transports the original’s fever dream intensity to Boston for a mob story that depicts the ways organized crime destroys every life it touches. The set-up could come off as gimmicky. Leonardo DiCaprio plays Billy Costigan, a cop who goes undercover as a mobster while Matt Damon plays Colin Sullivan, a mobster groomed from a young age to infiltrate the police. But it’s DiCaprio and Damon’s tortured performances as confused, conflicted men caught in traps built long before they were born, Scorsese’s technically dazzling filmmaking, and a supporting cast that includes Jack Nicholson, Vera Farmiga, and Mark Wahlberg that elevate a story that Scorsese described in a 2005 interview as set in a place where there is “no longer a question of good and evil. The two poles are interchangeable. All that’s left is the world as it is.”

10. After Hours (1985)

A time capsule of a chapter of New York in which yuppies, punks, artists, and assorted oddballs brushed shoulders in a still-untamed Manhattan, After Hours twists reality just enough to make it at once cartoonish and nightmarish. Made swiftly and cheaply after the collapse of the first version of The Last Temptation of Christ, the film stars Griffin Dunne as an office drone whose attraction to a stranger (Rosanna Arquette) sends him pinballing from one uncomfortable situation to another on a perilous all-night journey from one end of the city to another. The closest thing to a comedy Scorsese has ever made, there’s nothing else quite like it in his filmography, but there’s no mistaking it for any other director’s work.

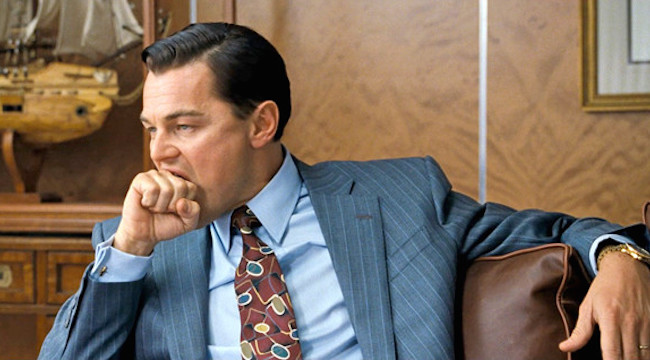

9. The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)

How do you depict odious acts without making them look appealing? For Scorsese, the answer has been not to try, whether depicting gangsters or cheats. Part of the thrill of watching Jordan Belfort (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Donnie Azoff (Jonah Hill) live a life of excess as they scam their way to stock market dominance is seeing how much they enjoy it. Sure, they hurt countless people along the way and destroy any chance of intimacy and connection with those around them, but it takes a long time for the high to wear off in this propulsive depiction of excess and unchecked greed. But look to the margins and you’ll see used-up lives. Look in DiCaprio’s eyes and you’ll see a man who’s abandoned humanity. The sting of the film’s final irony comes from the sense that it all could, and will, happen again.

8. The King of Comedy (1982)

A character as haunting in his own way as Travis Bickle (whom you’ll find a little higher on this list), aspiring comic Rupert Pupkin (Robert De Niro) dreams of making it big in comedy and finding an audience outside the basement of his mother’s house. When late-night talk show host Jerry Langford (Jerry Lewis, in a brilliant departure from the clowning that made him famous) gives him a brush-off he mistakes for interest, his ambitions take a desperate turn as he conspires with Misha (Sandra Bernhard), an obsessed fan, to kidnap Langford. That Pupkin and Langford have a lot in common becomes this unflinching satire’s darkest joke. Scorsese holds back from showing Pupkin’s comedy until late in the film. When we do see it, it’s not terrible. We also witness Langford returning to a lonely life far removed from the amiable persona he projects on television. Entertainment is a cruel business that wraps loneliness around winners and losers alike.

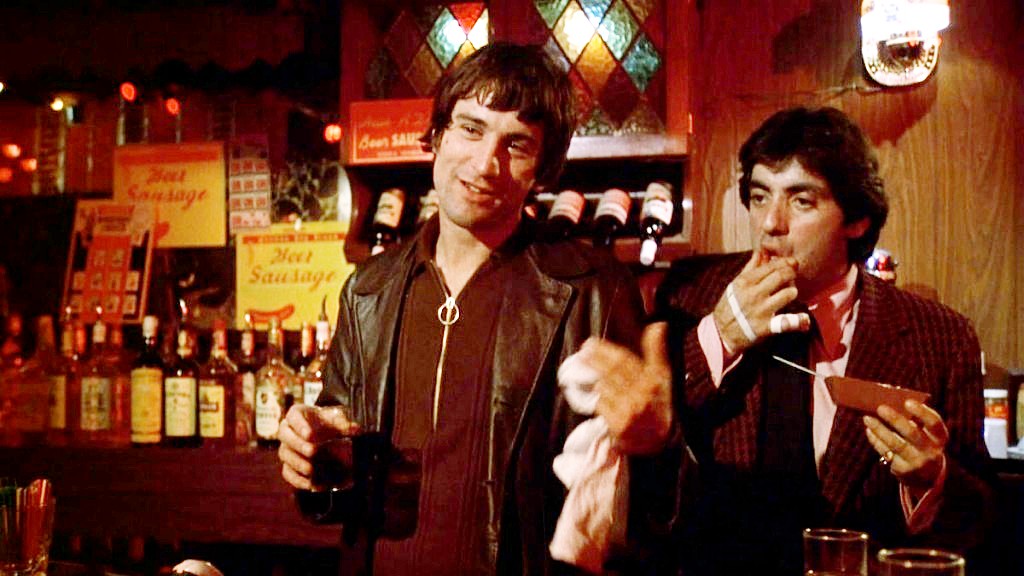

7. Mean Streets (1973)

Read enough interviews with Martin Scorsese and you’ll hear about three parts of his early life over and over again: a sickly childhood spent indoors observing the life of New York’s Little Italy going on outside, an interest in movies that blossomed into obsession at an early age, and a conflicted early adulthood spent among dubious characters. Scorsese’s feature debut, 1968’s Who’s That Knocking at My Door made a first stab at depicting that lattermost phase via the story of a young man confused and angered when he learns his girlfriend isn’t a virgin because of a rape, a discovery that he can’t reconcile with the Catholic values he’s internalized and the cavalier treatment of women he practices with his friends. Years later, Scorsese would reunite with that film’s lead actor, Harvey Keitel, for a film that expands the scope of that debut, exploring the backrooms, private moments, and violent eruptions of New York life as experienced by Charlie, a small-time debt collector (Keitel); Charlie’s girlfriend Teresa (Amy Robinson), whose relationship he keeps secret, and the self-destructive Johnny Boy (De Niro, in his first collaboration with Scorsese). It’s a bit of street poetry from a filmmaker already in full command of his talents and telling a story he was born to tell.

6. The Last Temptation of Christ (1988)

Scorsese spent years trying to film an adaptation of Nikos Kazantzakis’ psychologically complex retelling of the life of Jesus, even walking up to the line of rolling film on the project in 1983 only to see it canceled at the last moment. In the end, he wouldn’t be able to make it for a few more years, and for a slashed budget and on a rushed schedule. Then he had to watch as it became an object of heated protest when conservative Christians objected to its content, particularly the film-ending fantasy sequence in which Jesus (Willem Dafoe) imagines giving up the burden of divinity and living as a husband to Mary Magdalene (Barbara Hershey, who introduced Scorsese to the big years earlier). Yet the result is a reverent, deeply considered exploration of the meaning of Christianity made by a man who takes religion seriously, and who understands that true faith involves struggle and questioning.

5. The Irishman (2019)

Only in bare description does Scorsese’s three-and-a-half-hour story of a labor union leader/mob assassin sound like a return to familiar territory. It’s set in the underworld milieu he’s depicted before and reunites him not only with De Niro but also Joe Pesci and Harvey Keitel (to say nothing of producer Irwin Winkler and, of course, his longtime editor Thelma Schoonmaker). But the film has an autumnal tone all its own and it needs every second of its running time to arrive at its gutting final stretch, an invitation to stare into the abyss and contemplate final things. Along the way, he tells the story of Frank Sheeran, who confessed late in life to killing both Jimmy Hoffa (played as a kind of an American Julius Caesar by Al Pacino) and gangster Joe Gallo. The veracity of those claims might be dubious, but that’s not really the point. Instead, it’s an opportunity for Scorsese to raise questions about fate, history, the passing of time, the possibility of forgiveness, and the ways sin weighs on the soul, questions he’s been exploring since Who’s That Knocking at My Door, and which clearly still trouble him. Scorsese seems healthy and active and has many projects in the works. Hopefully, he’ll live to be a hundred. But he might never make a final statement as stunning as this one.

4. The Age of Innocence (1993)

In adapting Edith Wharton’s 1920 novel about life among the privileged in Gilded Age New York of the 1870s, Scorsese found a setting as rich in codes and casual cruelty as Goodfellas. Daniel Day-Lewis stars as a lawyer engaged to May (Winona Ryder), the right woman by society’s reckoning but drawn to Ellen (Michelle Pfeiffer), the wrong woman by that same reckoning. One of Scorsese’s most lyrical films, it offers a heartbreaking depiction of an impossible love while depicting how the impediments to that love operate together like gears in a machine. It’s bittersweet and lovely, but there’s real anger, frustration at the heart of a love story that understands how some wounds cut to the soul.

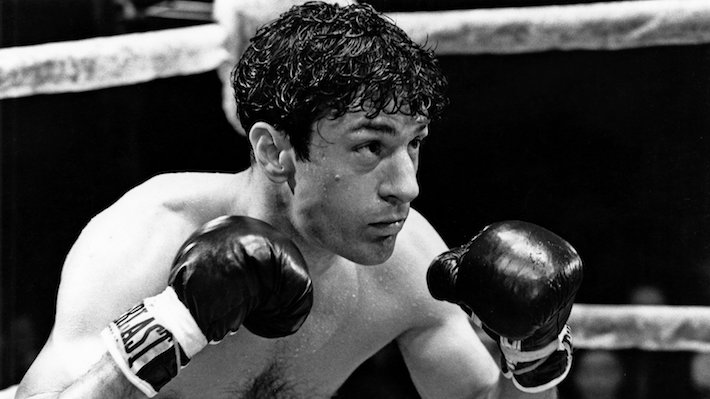

3. Raging Bull (1980)

Scorsese didn’t know much about boxing when he took on Raging Bull, but he did understand how easily success could turn to failure. Over the course of the film’s long gestation, Scorsese’s second marriage ended; his ambitious musical, New York, New York, met with mixed reviews and commercial indifference; his career prospects turned shaky; and a descent into drugs, depression, and suicidal thoughts climaxed in a scary hospital stay. He came to see his own life reflected in that of Jake LaMotta, the middleweight boxing champ whose self-destructive (and just plain destructive) tendencies led to a long fall from glory.

Scorsese reunited with De Niro and Schrader for the film, which he shot in striking black-and-white chosen in part to set the film apart from the many boxing movies released after Rocky. As usual, he meticulously planned the shots, bringing a balletic rhythm to the often brutal fight scenes. But the story is of a man with no control over his life, or himself. De Niro takes no steps to make LaMotta more sympathetic. He’s delusional, jealous, and misogynistic and his mistakes are all his own. But by staying so close to such an ugly person, Scorsese dares viewers not to see the humanity of even such a fallen man — and maybe see a bit of themselves as well.

2. Taxi Driver (1976)

Working from a screenplay written by Paul Schrader inspired in part by would-be assassin Arthur Bremer’s diary, Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Notes from the Underground, and a low point in Schrader’s own life, Scorsese crafted a portrait of profound alienation that doubles as a descent into hell. De Niro plays protagonist Travis Bickle as a man incapable of connecting with others who comes to blame the darkness inside him on the darkness around him, a grimy mid-’70s New York filled with porn theaters, pimps, and casual cruelty. What he can’t see, as he styles himself as an avenger of wrongs, is that his fascination with violence will do nothing to reshape that world.

Driven by De Niro’s hollowed-out performance, it’s a queasy film that walks a tightrope, wrapping both Travis’ alienation and the city around him in a kind of dark glamor — aided by Bernard Herrmann’s final score — without shying away from the ugliness and brutal consequences of his mental state. He’s a man who comes to see killing his only release. Hauntingly, he fits right into the city around him.

1. Goodfellas (1990)

A tour de force that never stops moving, Goodfellas both returns Scorsese to the underside of New York via a decades-spanning story and to the subject of men unable to prevent their own downfalls. Adapted from Nicholas Pileggi’s Wiseguy: Life in a Mafia Family, a non-fiction account of mobster Henry Hill’s career, Goodfellas plays out against the backdrop of a mafia, and a New York, undergoing profound changes between the 1950s and the turn of the 1980s. It’s no ordinary mob movie. Scorsese isn’t shy about violence, but it’s the attention to the day-to-day life of a gangster that sets it apart, the schemes mobsters engage in, the routines needed to keep those enterprises afloat, and the codes by which they live. It’s a crime story, but also a film about work.

In fact, part of what makes Goodfellas’s violence so chilling is that the film treats it as just a logical extension of the job. No one wants to commit murder — OK, maybe Tommy (Joe Pesci) occasionally wants to commit murder — but the business Hill (Ray Liotta), Jimmy (De Niro) and those around them engage in sometimes demands it. There are rules to follow whether for murder (“You got out of line, you got whacked”) or adultery (“Saturday night was for wives, but Friday night at the Copa was for the girlfriends”). Hill ends the film having lost everything and having betrayed his friends, but still unable to see his own role in his undoing. He’s learned nothing. Those watching, however, have ridden the highs and lows of a way of life they’d otherwise never glimpse — and witnessed a mirror-image version of the American dream in the process.