I’m going to cry when I see the Black Panther opening credits. I’ve told my family to prepare for it, and I have no shame about the emotional eruption I’ll feel when I lay eyes on the cinematic version of Wakanda for the first time. I’ve dreamed of the moment for 20 years, wanting the rest of the world to experience a place I’ve felt has been a home for me.

Since I was 12, T’Challa and the world of Wakanda has inspired me, loved me, and given me a creative outlet when I’ve needed to escape the realities of being a black kid in America. I love the characters as if they were relatives I’ve spent hours on end trading letter with. And it all started when I held my first Black Panther comic in my hand for the first time.

I didn’t quite understand it at the time, but the connection to someone who looked like me in a store full of pictures of white (and purple, and green and anything but black) faces, is why I remember precisely the moment I first grabbed Marvel’s 1998 Black Panther #1 off of the shelf at my favorite comic book shop. I’ve gone on my comic book runs pretty much every Wednesday for 20 years — a thousand trips give or take. But holding Black Panther, written by Christopher Priest, who is black, for the first time is one of a handful of those thousand trips that I can close my eyes and relive. I remember looking at the cover — which is framed in the wall of my home office to this day — Panther scaling a New York City skyscraper, his claws sheathed with light reflecting off of his gold bracelets. He was at once majestic and menacing. A superhero, yes, but, as I’d soon find out, barely. Yes, he fought villains like every other superhero, but what made him unique was that his motivations were political. It was Wakanda First for T’Challa and anyone who threatened his nation could feel his wrath. He was grounded in the simple premise that his country’s well-being came first and foremost, beyond friendships, superhero protocol or even a belief that goodness conquers all. Protecting his people was his ideology, which made him more of a pragmatic figure than, say, a Captain America. If he had to get his hands dirty, he would, and maybe even like it a little bit.

I wouldn’t know how much I needed Black Panther in my life until later or that the stillness of holding the book would be etched in my brain all these years later. I just knew that I was holding something that would stay with me forever.

I didn’t buy Black Panther because I was looking for black representation. I bought it because Marvel was pushing its new Marvel Knights line, where popular creators — director Kevin Smith and superstar artist Jae lee among them — would try to rejuvenate D-level heroes for a new generation. They were soft reboots of then nearly forgotten characters consisting of — believe it or not — Daredevil, The Punisher (via miniseries), The Inhumans and Black Panther. I was vaguely familiar with Black Panther, having seen him in a random episode of the short-lived 1994 Fantastic Four cartoon, but that was about it. But when I held that book, I know what I felt. I felt a familiarity. I felt that I was seeing myself on the page for the first time.

Marginalized people know what representation means. Even when we don’t. Believe it or not, we understand the concept of seeing people who look like us even if we aren’t quite sure what we’re looking at. It’s a feeling of not knowing what has been missing until that thing finally appears in our lives. My son, for instance, at the age of five has the understanding of race that a typical five-year-old posses. Which is to say, he has none whatsoever. Yet he still loves Star Wars’ Finn and has called him “Brown Boy” without prompt or explanation for two years. Whether we’re people of color, women, LGBT folk, disabled and any underrepresented group not listed, we innately notice the void being filled whether we have a tangible cognizance that the void even exists in the first place. And even if we can’t define the feeling, we know the elation of that void being replaced by images of people who look, feel and love like we do.

In fact, I don’t remember reading any books written or drawn by black people as a kid in the ‘90s and the books that starred black characters were mostly mini-series that weren’t ever any good. There was Spawn, whose mature subject matter meant I couldn’t bring it home as a kid. When I got older and read those books, I appreciated them but Todd McFarlane wasn’t exactly James Baldwin when it came to understanding the nuances of black life, though I appreciate the effort. And as much of an X-Men fan as I was — and, really, who wasn’t in the ‘90s? — the Civil Rights allegory of Mutant vs. Human only went so far, especially when the intersection of being black and a mutant was never properly addressed. Characters just never talked about how being black and a mutant was different than being a white mutant, or what even if the sudden appearance of people with new skin colors changed racial dynamics. There was just silence. I loved Storm and Bishop, but, oftentimes, characters are only as representative as their creators. There was always something missing. They didn’t fill the void of representation I didn’t really understand existed.

Black Panther changed all of that. Priest — who was hired as the first black editor at Marvel Comics before writing Panther and who is currently working on DC’s Deathstroke after stepping away from comics for years — is known for his non-linear storytelling He jumps from scene to scene, creating a disorienting timeline of misdirection, unreliable narratives and plot-developments that you’ll miss if you skip half a sentence. And, quite frankly, it was too smart for a 12-year-old. But there were moments. Glorious moments that made me swell with pride.

Priest gave us more than a hero. He showed us a T’Challa who was one of the planet’s most powerful politicians who had the world by the nuts financially due to his export of Vibranium. We got a calculated Black Panther who was two steps ahead of everyone else. And we got a badass motherf*cker who punched out the literal devil. And all that was in the first handful of issues.

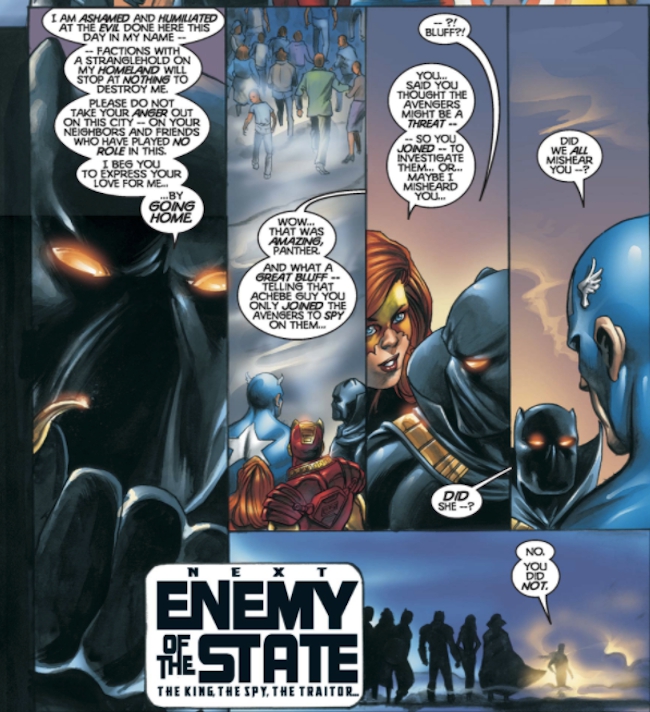

For me, the defining Black Panther moment, the one that made him my favorite comic character, came in the final three panels of issue eight. That’s when he revealed that he only joined the Avengers in the first place to spy on the American superteam and see if they were a threat to Wakanda. Firestar asks Panther about his confession in disbelief. Panther walks away without hesitating and essentially confirms that he said what he said without skipping a beat. In that moment, Priest undid decades of tokenism that had Panther as a bland tagalong while also giving a logical explanation for why a king would leave his home country to fight villains in America. He wasn’t just the Avengers affirmative action hire anymore. He was the underestimated genius who wore his Panther mask and Dunbar-ian mask at the same time.

I wanted to be him.

It was his sureness. The way he stood in Captain America or Iron Man’s face to coldly let them know he was the dominant force in the Marvel Universe. The way he could walk into the middle of a chaotic Wakandan Civil War without flinching and reveal he had the entire situation handled before it even started. When Panther overcame the the United States and Russia and the mafia’s conspiratorial attempt to dethrone him and destabilize Wakanda — my first exposure to the very real traditions of Western nations sabotaging flourishing black countries — I felt a beating drum of accomplishment in my chest. I wanted to face oppression with the same unflinching defiance. I wanted to plan my way out of expectations. I wanted to kick ass. I wanted to be Black Panther.

It was his confidence that I wanted. His cold, borderline asshole-y flair that I dreamed of possessing. Especially as a 12-year-old, awkward black boy without the self-confidence to sufficiently fight back against low expectations or being short-changed based on my skin color, something that I noticed was occurring with more frequency that year. Seventh grade was when I really started to realize how white people looked at me. I had grown into the right size needed to pass the curve of being considered sturdy enough to get treated like an adult. Where racism manifests itself in blatant, dangerous ways. This was when my theater teacher told me that a character I wrote needed worse grammar if he were going to be black. When my “gifted” teacher pulled me outside to tell me she thought I was racist against white people, because she saw me joking with a white girl and thought I was bullying her. When sarcasm gets seen as aggression. When white ladies clutch their purses and children when they see me walking around the mall. When cops yell “get the fuck out of here” when I’m playing tennis with my friends.

I wanted to react to these moments with the cold, calculated destruction of my enemies the way Black Panther did. I’d fantasize about revenge. Not violent revenge, but schemes of ways to demoralize and mortify my teachers, making them regret the way they’d treated me. I dreamed of plans where the teachers would show up and realized I’d bought the school. Or how I could use some cloaking device to spy on them calling students niggers in the teacher’s lounge and by the time they realized what happened, their conversations would have already been playing on the intercom. I wanted the calculation, coldness and brilliance of T’Challa. But I obviously couldn’t be him. So I did the next best thing: I retreated to his world.

I would consume Priest’s Black Panther, inhaling each issue on a monthly basis for five years. I saw a Wakanda, uninhibited by the gaze of white colonialism. How great we could be if left to our own brilliance. I wasn’t looking at pages of a comic. I was looking at a crystal ball that showed my all of my potential acted out in Technicolor.

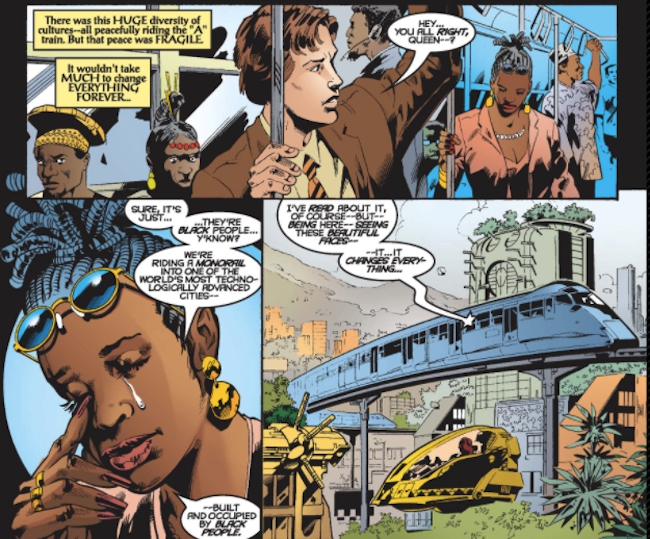

For example, in issue 20, Queen Divine Justice, a New Yorker who was recruited to join T’Challa’s Dora Milaje security force and a character who acts as a proxy for the reader, takes public transportation in Wakanda for the first time. She’s surrounded by the Africa she’d always hoped for. Regality. Technology. Intelligence. An Africa that currently exists somewhere in the margins of media coverage, and is only magnified by Priest’s Afrofuturistic Wakanda. Passengers are listening to music on wireless headphones (which were pretty much science fiction in the late ‘90s) while flying cars wiz by outside near garden-topped skyscrapers.

She starts crying: “It’s just…they’re black people…y’know? We’re riding a monorail into one of the most technologically advanced cities built and occupied by black people. I’ve read about it, of course, but, being here, seeing these beautiful faces. It changes everything.” Justice was a proxy for the audience, an outsider in Wakanda and in that scene she shows the importance of what Priest presented. That scene also personifies what it’ll be like watching the movie, too. It’s one thing to see the majesty of Wakanda on a page. But to see it in moving, majestic color in a movie theater will be damn near a religious experience.

Black Panther became black excellence to me. He was a symbol that transcended the heroics on the page. I’d adorn my walls with Black Panther posters. My work desks with action figures and statues. My college mixtape was called T’Challa. Don’t ask. I’d always thought it was silly for people to love fictional characters like they were real, but Black Panther was that real hero to me. My self-care when I needed to escape.

Christopher Priest left the book in 2003 and the title would fall into a disappointing malaise. Reginald Hudlin, who is a prolific and important movie producer, just isn’t good at writing comics. His run at Black Panther was full of cliches, poorly conceptualized plots (Skrull Martin Luther King and Malcolm X come to mind) and a marriage to Storm that is remembered fondly by people who saw the comic book covers but never read the actual stories. It all broke my heart. Despite those missteps, the Panther character would maintain its majesty that Priest helped usher in. He would be part of the Illuminati, Marvel’s brain trust of powerful heroes. And he’d even hold the Infinity Gauntlet. But the Black Panther books themselves couldn’t hold up to the standard set in the Marvel Knights run.

In the last couple of years, in preparation for the Black Panther movie, Marvel has made a new effort to push the character, handing over the reigns to Ta-Nehisi Coates, whose stories bounce directly from the pages Priest wrote 20 years ago. In fact, the movie will feature many of the staples from Priest’s work — most notably the characters of the Dora Milaje, and Everett K. Ross. I honestly never thought I’d see this much attention paid to Black Panther, or a movie that looks to do Priest’s run justice. Reading Coates’ run and seeing these characters I loved so much feels like catching up with a family member and never having to go through a long re-introduction before we’re back to laughing like old times.

I know the movie won’t fix the world’s problems. It won’t change anyone’s living conditions. But for a couple of hours, I’ll be in a theater experiencing a world I’ve fantasized about for two decades. And this time I won’t have to see it as a place I retreat to. I’ll see Wakanda as a home that’s finally been opened for the world to see. Welcome. It’s lovely here.