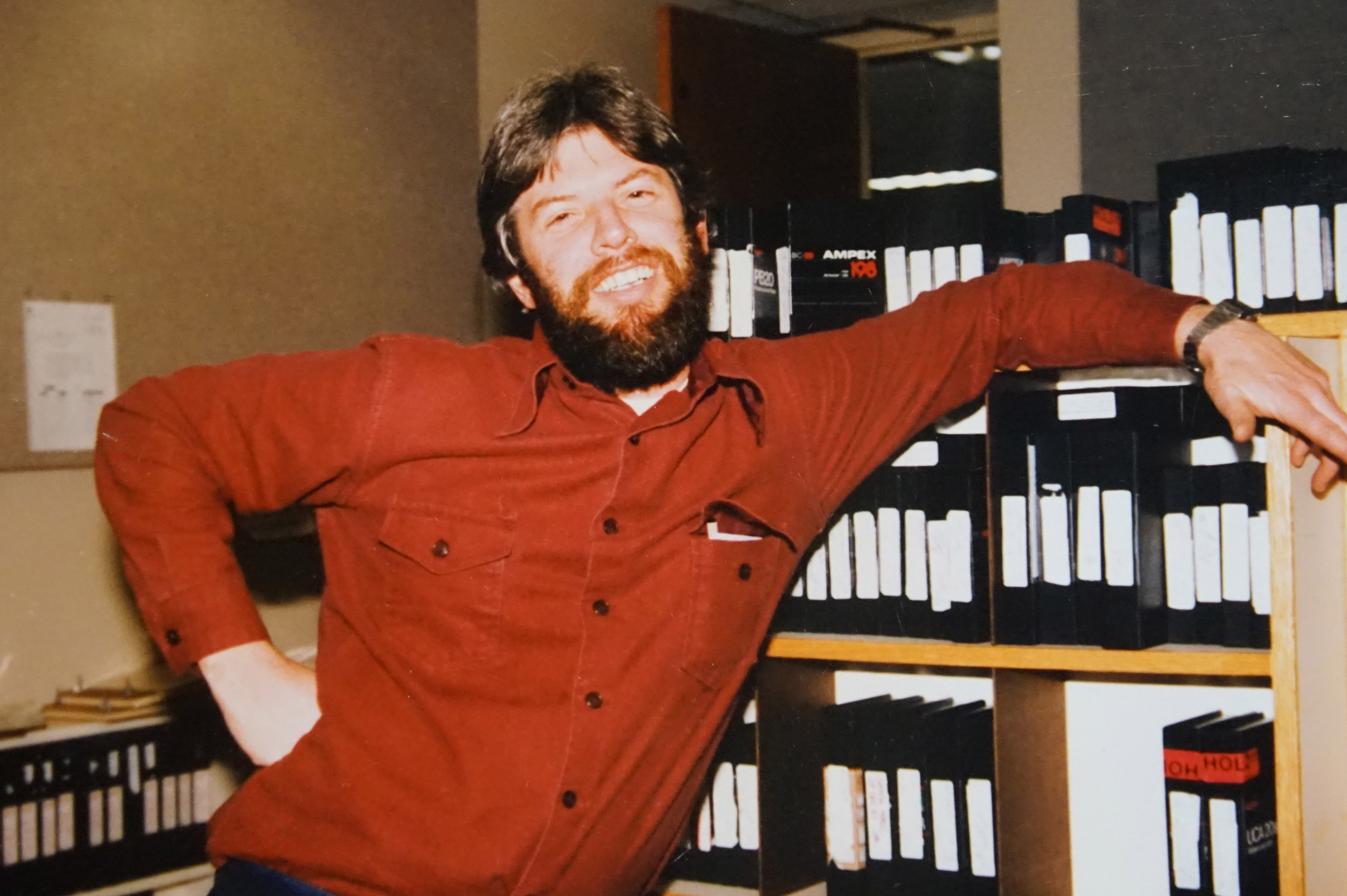

In my family, Milt Ritter has always been something of a folk hero. He and his wife Chris — my sister’s godparents — are hippies who never burnt out. Instead, they always seemed skillfully adept at navigating the trappings of capitalism without forgetting their humanistic, “kindness first” belief system. Chris taught grade school with my mom in Canby, Oregon, while Milt was a cameraman for KGW, Portland’s NBC affiliate.

When the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh and his followers arrived in Wasco County, Oregon, Milt was dispatched by the station to get footage of the goings-on at the commune. Over the course of the next four years, he and other staffers at the station spent extensive time on Rajneeshpuram and became quite friendly with Ma Anand Sheela — the wildly controversial secretary to the Bhagwan. Eventually, Milt’s footage from the commune was archived by the Oregon Historical Society and was used heavily by directors Chaplain and Maclain Way for the popular Netflix documentary series Wild, Wild Country.

With the show currently sparking so much conversation and controversy, I spoke with Milt about his thoughts on his time at the ranch/commune, his memories of the Bhagwan, and everyone’s favorite topic: the razor-tongued Ma Anand Sheela.

It’s wild to watch the documentary because I know so much of the footage is yours and it almost seems like they had B-roll for every single anecdote.

True enough. There were some moments that didn’t match up, but nobody would know except those of us who knew the place. It’s not often that you have this much footage. A lot of it from me, but I also think they got some footage from the Rajneeshees, because they were always filming everything. The place was documented like crazy. Local news stations, national networks… everyone was there.

How did you feel about Wild, Wild Country? You were interviewed heavily in the OPB doc on the subject, so I’d imagine you would have thoughts on how these new filmmakers executed it.

I think they did a pretty good job of telling the story. I certainly didn’t see anything grossly wrong with it. They leaned heavily on the work of Les Zaitz — the Oregonian investigative reporter who wrote the famous 20 part series on the ranch — and interviewed him in the doc. He takes a pretty harsh view of Bhagwan with regards to what he knew and didn’t know.

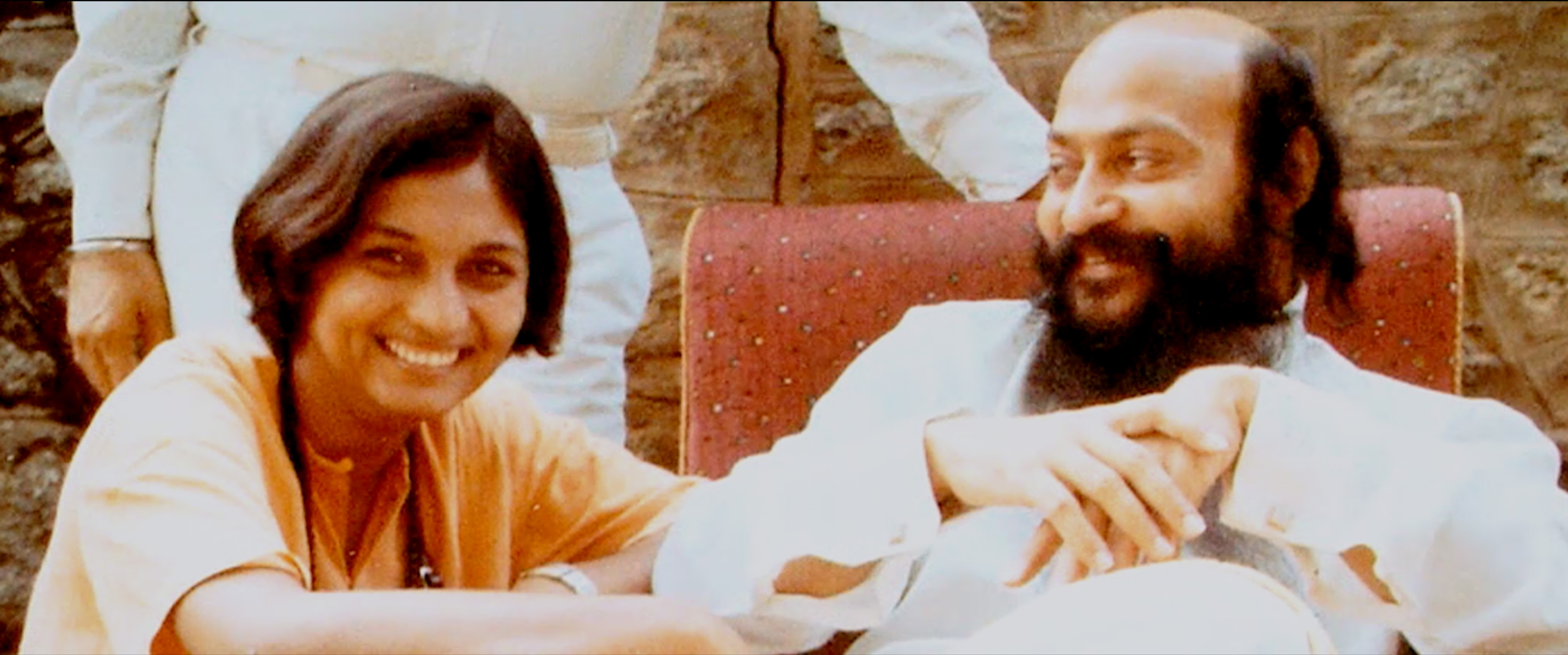

I tend to be a little softer on him. I believe that he didn’t know what Sheela was doing. I think he knew some stuff and probably encouraged her to do some stuff but didn’t realize to what extent she was breaking the law to do it. I really got the sense that he didn’t know that things had gotten out of control until the very end, whereas Les Zaitz really thinks that Bhagwan was having Sheela do these things for him. And of course, nobody really knows at this point.

One thing that surprised me: the language and the tenor of how people spoke about these newcomers is clearly xenophobic. When I listen to your archival interviews, the way the Antelope locals speak feels really troubling from a racial and religious freedom standpoint.

That was troubling when we were covering it, as well. It goes on all the time — people don’t understand something so they’re afraid of it, then they get angry about it. You want to think that Oregon is a groovy place and really tolerant but people came out of the woodwork to fight the Bhagwan and it became a big deal. It wasn’t uncommon back then to see people wearing shirts that said “better dead than red” or “bag the Bhagwan.” There were a lot of people who were pretty vocal. And I’d look at them and go, “You guys have no idea what’s really going on up there and who these people really are.”

You have a much more positive view of the Rajneeshees — which is what I’m left with after my research too.

I’m conflicted — I was conflicted then and I’m still conflicted — about what happened there. Because they were clearly in violation of Oregon’s land use laws. And the land use laws of Oregon are near and dear to me. I love the planning we’ve done here. On the other hand… I love what they were doing with that ranch. They were really writing the rules for large-scale organic farming. They were one of the first groups to do it. For a long time, really, it was, “If you want good food in Central Oregon you go to Rajneeshpuram.” At that point, Central Oregon had maybe a couple of good restaurants, but you could always get good food at Rajneeshpuram.

Oh, that’s interesting. So, people would actually go on to the ranch to get food? Or you would go to their café there in Antelope?

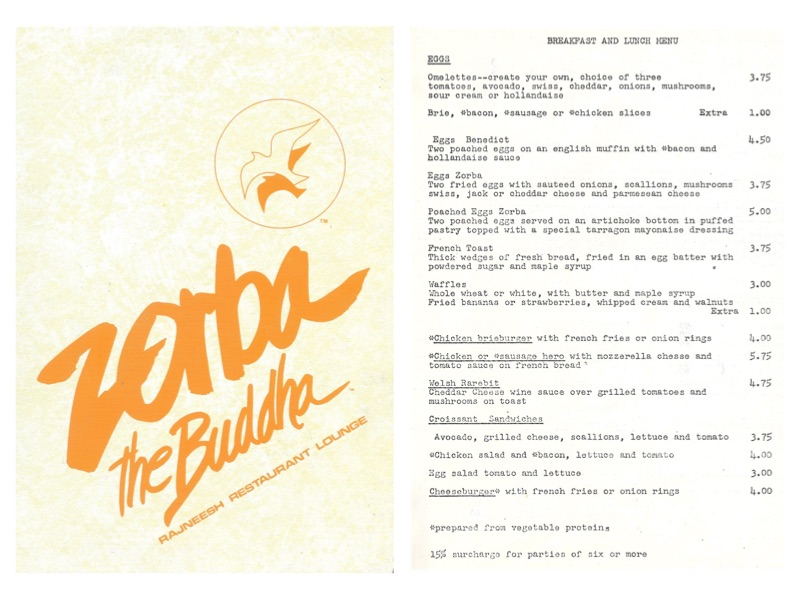

No, on to the ranch. They had a shopping center there and there was a couple of restaurants. “Zorba the Buddha” was a big restaurant that had great organic food and drinks.

They were ahead of their time in some ways then?

You had to admire them on one hand and then go, “You know you guys, this isn’t exactly right.” I loved what they were doing and I hated what they were doing. I think a lot of us in the press felt that way. Especially when Sheela would get on her high horse and start cursing at people and calling names. That was always… not so great. But then, on the other hand, I really liked Sheela. I hung out in her house a handful of times and I liked her. She was fun to be with. It was one of these things where I felt, “I love you, Sheela, but I hate what you do.”

But even that was a strategy for her, right? Even those outbursts were part of her plan?

We asked her once, “Why do you fly off the handle and call Oregonians names?” And she said, “It works for us. We get most of our money from Rajneeshee communes around the world and if we can show to them that we’re being persecuted, they’ll send us money to fight our case.” So she’d say something, the Oregonians would react with protests, they’d film it or record our news segments and send it to communes around the world and that’s how they’d get their money.

One of the things I’ve troubled over is how the Rajneeshees were treated like a “sex cult” and still are treated that way, when their actual feelings about sex seem very positive. Was there just an overarching fear of sex at that time and that was a stigma they couldn’t get rid of?

A lot of those protests were coming from conservative Christians and… they hate that whole sex thing. It became one of the things they were really, really focusing on. They’d pick scenes out of the documentary Ashram by the German filmmaker. They point at that as proof that these people were immoral and didn’t deserve to be in Oregon.

People want to call this a cult but I don’t see that. Did you see control? Did you see abuse? Did you leave repulsed by these people?

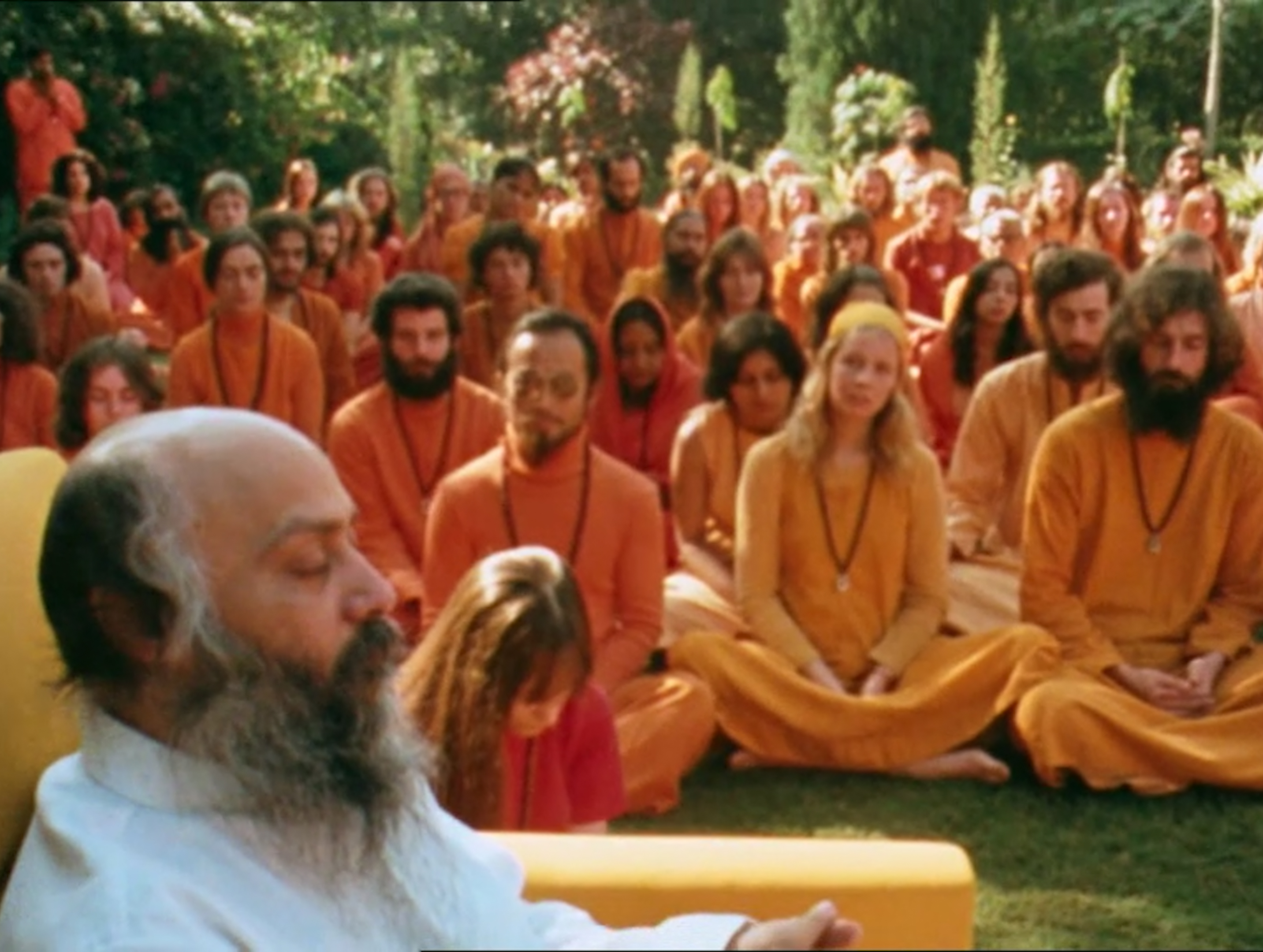

No. There is a fine line in any religion, and the Rajneeshee thing… was it a religion or just a movement? The Bhagwan hated religions. Sheela made it a religion but I remember the Bhagwan saying, “You will not make dogma out of my words.” But there is this sort of thing when people are so enamored with somebody, a leader or whatever, they become these followers that… it’s sort of akin to mind control but nobody’s forcing them to do anything, it just happens. Look at Beatlemania. People become so blissed out in the presence of somebody that they lose rational thinking ability. And that was clearly happening out there. These people were enamored beyond belief with Bhagwan and they would do anything for him.

The deal was when you worked at the ranch you worked 12 hours a day — they didn’t call it work, they called it worship. And nobody was forcing them to do it, they could leave the ranch if they wanted. The line to get into the ranch was huge — every Sannyasin in the world wanted to live at the ranch with Bhagwan. People hung onto their right to live there, on their ability to live there, as much as they could.

Nobody was forcing them to do anything as far as I could tell. Sheela’s gang started becoming a little controlling, especially when somebody stepped out of line, based on what they were thinking. There’s the story where they stabbed somebody with a needle or something, you know? Other than that, I think there was nothing going on. No mind control or anybody forcing anybody to do anything.

Yeah, it just never seems like it, although… did you ever come into contact with Win McCormack (the founder of Tin House, co-founder of Mother Jones, and current owner of the New Republic)?

That name is so familiar, I probably have. I don’t remember.

He recently wrote a book about his time covering the Bhagwan, along with a huge article about Wild, Wild Country, and he focuses his frustration at how forgivingly, and not like a monster, the Bhagwan is being treated. He feels like this guy … he analogizes the Bhagwan to Hitler.

I’m not buying that. I know there are people that feel that way. Among journalists… I think most journalist kind of waffle on their feelings, like I do, about the whole deal. I don’t think most people, especially journalists, would hold those views.

There was a guy who appears right at the end of the documentary, Bill Driver, and I don’t even think he’s listed by name in the documentary, but he was a journalist who was what I’d call an “agenda-driven” journalist. He was really anti-Rajneesh. All he wrote was anti-Rajneesh articles. The ranch finally got around to just banning him altogether. He was one of those guys who thought that Bhagwan was evil and the whole ranch was evil.

I have a piece that I did when I was at KGW where we followed Bill around for a day, when he tried to go to a public meeting at Rajneeshpuram and they just threw all kinds of roadblocks at him. We just followed him through this process. It was pretty amusing.

Anything else you want to say? Looking back on it now, you were a big part of this thing. You were on the ground for this historical event that is now kind of resurfacing that is also, I guess, a really deep part of America’s history, right? Our discomfort with different religions, our rejection of what we don’t understand. Xenophobia and fear of the other are some of the biggest issues in our country. How do you feel about it all, looking back now?

There were two big stories that I covered when I was in news. One of them was Mount St. Helens and the other one was the Rajneeshee. They’re both pretty freaking amazing stories, but this is the story that nobody would believe if you wrote a book about it. People go, “Man, that wouldn’t happen. People wouldn’t let that happen!” or whatever. I think it really is, now that we have a little bit of distance from it, it really is sort of like human nature and the human experience wrapped up in one little event that lasted five years, in Oregon.

You have everything from a guru who is like loved by all of his followers and his whole thing of just love and bliss and trying to create a Utopia, to intrigue where you have these people trying to kill public officials and government workers. The very first bioterrorism event in the United States, which nowadays wouldn’t seem like such a big deal because that kind of stuff happens. Back then they were breaking ground. [Chuckles] They were breaking grounds in lots of areas.

Really, it’s a story that shows the good and the bad in people. What people can do, I mean people go, “How did the Egyptians build those pyramids anyhow? Oh, my God, that’s amazing!” Then, you look at what the Rajneeshees did in just a few short years with this ranch that was completely depleted of everything. It was so overgrazed and in such poor, poor shape. They turned it into an oasis. They planted tens of thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands of saplings along the creeks. They replenished the riparian zones and then they built that big dam and all those buildings. Some of them were not small buildings. It is amazing what they did. The organic farms, the meeting areas… it really is amazing what they did in such a short period of time.