DeMar DeRozan jumped into some strata with which he was previously unfamiliar when he dropped 52 on the not-there-yet Bucks on Monday. On the whole, he’s the driving force behind a Raptor offense that hasn’t seemed to miss a beat this season.

Crucially for Toronto, it isn’t just three-pointers with DeMar, though he’s nearly doubled his attempts and five threes on Monday put him at a solid-enough 35 percent on the year from long range.

The 28-year old has turned into an all-around possession force for his Raptors, developing into a potent threat as a passer and all-around progress-encourager with his movement and also butt, one he uses to set screens and inhibit defensive confidence with.

But DeMar’s not the first player at his position to make a leap so startling.

Dwyane Wade might be the most recent, prominent, hire. Flip your phone up and film:

In Year Two of a career that will last for as long as NBA teams provide five-star hotel rooms for its players, Wade made strong notice of the league’s new insistence on calling hand-checks.

This was still 2004-05, stompers like Larry Brown and Lawrence Frank and Wade’s own Stan Van Gundy were still around to control the action. D-Wade got to serve as an unexpected beta tester just two years removed from obscurity up in Marquette, gleeful as the referees began to call the sort of shoves that would make even Bryant Stith wince.

Dwyane was all like, you mean it’s still slow and spread out but they call everything, now? and the NBA was like YEP! and suddenly Dwyane Wade was better than Kobe.

From his rookie to third season he nearly doubled his per-minute freebie attempts, winning a championship in his fourth year by shooting more free throws in one 2006 Finals series than Kyle the Shy Lefty from Athletes in Action usually took in front of the kids on an average Saturday morning.

Bryant made his own metamorphosis in 1999-00, his first season under Phil Jackson with the Lakers. The eventual championship year saw the star in civvies to start the run, leaden with a broken hand.

In surmising what lay ahead in his first season stuck in a triangle, Bryant famously lulled himself sleepy with an in-

game meeting with Michael Jordan hisself in 1997 …

… but it didn’t end there, because 1999-00 also saw him building proudly on a 1997 chat with Reggie Miller about the sort of step-back jumper that had previously eluded the teenager in triple-threat stance, especially when run in Bryant’s pre-NBA scrums against stalwarts like Aaron McKie and future teammates like Eddie Jones.

Bryant would go on to use that step-back to destroy Miller’s Pacers in the 2000 Finals, also savagely relying on the defensive and offensive lessons gleaned from Gary Payton during a discussion about post-defense (because this was 2000) during that season’s All-Star Game.

Nobody should have ever talked to this guy. Let’s learn from that.

Ray Allen wouldn’t take issue with that concept, so assured was his start to his career that he more or less maxed-out from the beginning. Unable to recognize as much, George Karl became upset and traded him and later explained why to Charley Rosen:

For Karl, however, the trade was a no-brainer. “Ray Allen was nothing but trouble,” Karl says. “We had no choice but to get rid of him.”

(These are the sorts of finds and eventual goofs we present every day over at The Second Arrangement.)

Vince Carter was initially presented as something altogether more severe than Ray Allen, but by his third season Raptors fans spied him shooting as many per-possession treys as Mr. Allen launched the year before. Something had flattened, alright.

Carter is a legend and Hall of Famer and mensch but his best run came after he was traded from Toronto to the Nets midway through 2004-05. He got his act together when it counted the most to him – in time to piss off Raptor fans.

Finally interested, he literally ran and shot more as a Net. He rebounded more. He passed and assisted way, way more. He stopped telling the other team the plays. Vince earned more free throws and, suck it Toronto, improved his free throw percentage from 69 percent as a Raptor to 81.7 percent in New Jersey.

The 2004-05 season proved to be Reggie Miller’s last as an NBA pro, he could have played a few seasons longer and I bet it ducks him to this day. For such an out-there guy his sleekest accomplishments – an unused ability to play ball deep into his 40s, his fin de siècle breakout – are delightfully nuanced.

Miller came to unofficial Pacer training camp during the lockout months of 1998 with Jordan’s inside-out work in the previous spring’s chilly Eastern Conference finals still ringing in his ears. Stuck with achy knees and no three-point jumper to speak of, Michael worked the refs and the angles and open spaces in clawing a seven-game victory over Miller’s Pacers, the pair’s lone postseason duel.

The stats won’t show it, nothing blips in any of the attempts or percentages, but Miller was a fantastically potent player for the two seasons under Larry Bird that he had left, starting in 1999. It was a figurative show come to life: Jordan was gone and eyes were so drawn to Miller as he peeled off screens to collect his triple-threat prize, that the Indiana offense flourished like mad in the NBA’s coldest years.

Top ranked offensively in both seasons under Bird to follow, with Reggie looking more and more the complete shooting guard by the minute as the run ended with that 2000 Finals trip.

Other approaches were even subtler.

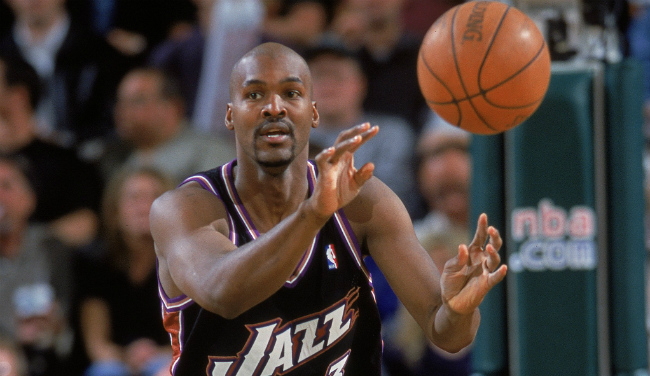

Bryon Russell was riding high with a five-year, $20 million contract entering 1997-98, the payoff for a breakout year the season before as a member of the Jazz, security after a career previously spent on the fringes. Strangely, though, to begin his stardom season, the swingman asked out of the starting job he earned the season before.

Jerry Sloan, after considering a pile of kindling in reserve, decided to start Adam Keefe in his place.

Russell “re-considered,” after a month, but with caveats:

“It will happen eventually,” said Russell about re-entering the starting lineup. “I’m not trying to rush it. The team is playing well together and Adam is playing well. Whenever Coach gets ready to put me back in the starting lineup, then I’ll be ready.”

That call wouldn’t come for months, not until Utah’s season seemed in danger at the hands of the Tim Duncan-encouraged Spurs in May, when Russell re-entered just in time to keep Utah’s championship hopes alive.

His springs saved, Russell averaged double-figure points in a sweep of the Lakers and played 48 minutes in Utah’s Game 1 win over the Bulls in that year’s Finals. He had enough legs to be there, in the end, working nearly-accurate defense in the face of Michael Jordan’s last moments as a Bull.

(We needn’t fully explain the cottage industry that blossomed, for Mr. Russell, as a result of these machinations. Just months after signing that $20 million deal.)

The NBA is filled with these sorts of stories.

John Salmons was allowed to play tons of minutes and shoot tons of shots for teams just because coaches thought he looked like what they assumed McCoy Tyner looked like. Both Kai Winding and J.J. Johnson were offered contracts despite their status as trombone soloists, and the run-and-gun ABA is even crazier – dig James Silas’ slow ascension into a steadier and steadier combo guard with improving lead playmaker skills!

Not all of the gambits worked.

Doug Collins’ attempt to make a possession-sealing “point guard” out of Michael Jordan probably added years to Collins’ life, and we were worried about the guy. All it gave the Bulls was the nine and a half seasons of respect it earned before Russell Westbrook capped off his NBA career with his first triple-double against the club, prior Westbrook’s retirement midway through 2017-18.

James Harden thought he had to make friends where Kobe could not – Dwight Howard – but all James Harden had to learn was that he needed to make friends with himself. Jordan didn’t need to make The Leap, his was assured the moment he first felt sweat on his widdle baby brow, and Oscar Robertson never actually jumped.

Robertson moved, though, once Kareem Abdul-Jabbar reminded Oscar that the Big O wasn’t looking at Paul Silas in the post, anymore. And Jerry West is something different.

A hybrid guard from start, West was still allowed to dominate the ball for years during his prime run, he developed all the usage habits that we’ve come to expect from players of a certain position, all the reason to stay exactly where he wanted to be, thank you very much.

At the dawn of the 70s West moved to play point guard full time alongside doughy super-scorer Gail Goodrich. Jerry was 33 at the time and point guards were way faster than him even then, but he dug in.

This wasn’t full benevolence in action – West and manned the position before alongside scorer Jim Barnett, the tiny Johnny Egan, and Walt Hazzard in cooler lineups – just a guy that wanted to get it right, this time.

And he got, this time, a title. Later Earl Monroe would achieve the same prominence as a Knick alongside Walt Frazier, backing off the ball as West and Robertson had taught in their advanced years.

Though it didn’t make his descent any less startling, we never dreamed such a slide-over from Allen Iverson. Kobe’s career end was replete with excuses dragged from his era, and it’s telling that three of the position’s greats (Ray Allen, Miller, Clyde Drexler) all retired with really good years left on those legs.

There Wade is, though, doing the best he can with the NBA that sprung up from rules he once perverted, on primetime ABC. An open game demands that nearly everyone can shoot now, so D-Wade has to go dirty until the very end. Check the stats: Wade’s succeeding.

So is Vince Carter, happy to play the good version of Johnny Neumann for teams that badly need his everything, and Bryon Russell just booked himself another gig hosting Thursday Trivia Night. They let you take home a styro box from the buffet!

It’s breathing in Toronto: DeMar DeRozan is doing more than stacking numbers in different slots. This is intelligence and collaboration and most excitedly evolution at work.

Lucky go the Raptors, for once.

Kelly Dwyer produces The Second Arrangement, now featuring near-daily Behind the Boxscores in most episodes, at tsa.substack.com. New subscription plans start at $5 a month!