On July 3, 1971, Jim Morrison died in a Paris bathtub after he [extremely Jim Morrison voice] slipped into unconsciousness. But even though The Lizard King has been dead now for 50 years, people keep on burying him.

The late lead singer of The Doors has been slagged by contemporaries like Jerry Garcia (“I never liked The Doors”), Lou Reed (The Doors were “stupid”), and David Crosby (Jim Morrison is “a dork”). He has been listed among the worst musicians of all time, and inspired podcasts about how much his band sucks. On Twitter, he has been linked to the launch of the Vietnam War, of all calamities, and even inspired disgruntled fans to burn his infamous biography, No One Here Gets Out Alive, because he’s “a bad role model for youth.”

With the exception of Eric Clapton — who to be fair is way, way out in front in this regard — I don’t think that there is a significant figure in classic rock history whose reputation has taken a worse hit in the past several decades than Jim Morrison. And I think I understand why. Because I used to also hate the guy’s guts.

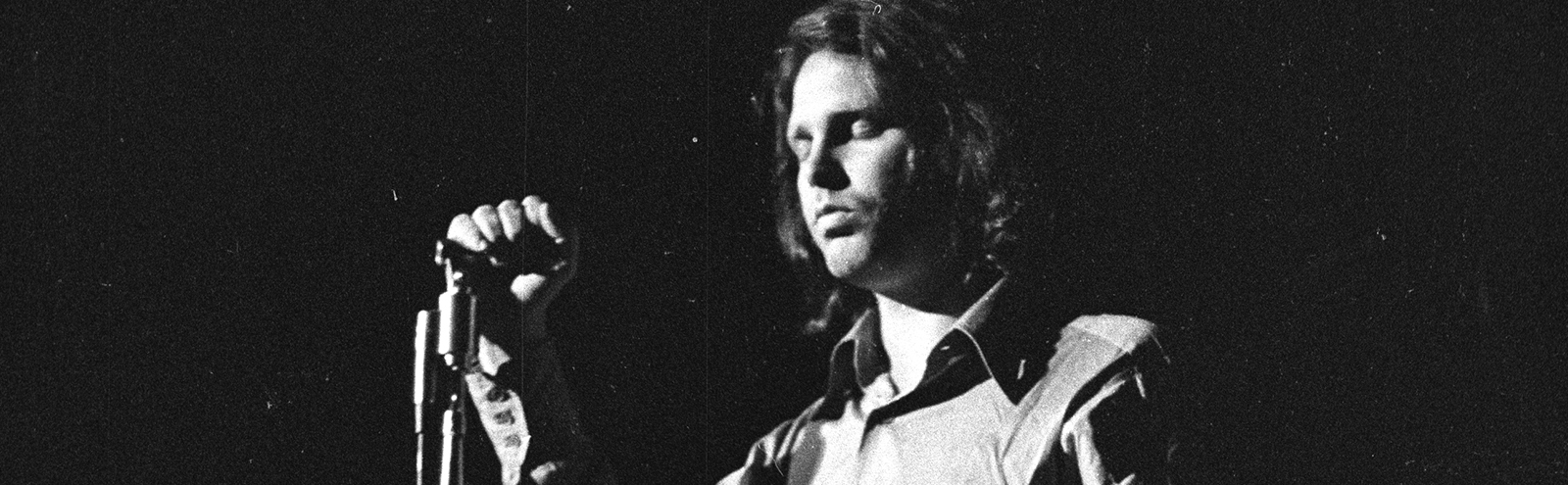

I came of age as a music fan in the early ’90s, which coincided with a wave of Doors revivalism inspired by Oliver Stone’s bombastic 1991 film, The Doors. At first, as an impressionable 13-year-old, I thought Jim Morrison was pretty cool. He sang in a deep, evocative baritone that seemed to signify a mix of sexual mystique and disturbing morbidity. Also, he could wear the hell out of a pair of leather pants. He seemed like a prototypical rock star. He drew me in.

But it didn’t take long for me to change my mind about Jim Morrison. And, again, that had a lot to do with Oliver Stone’s movie. In the film, Val Kilmer plays Morrison as a hellbent hedonist who is both an immature child and a self-immolating egotist. It’s a portrait that syncs with Jerry Hopkins and Danny Sugerman’s 1980 book No One Here Gets Out Of Alive, which ranks with Stephen Davis’ Led Zeppelin bio, Hammer Of The Gods, as one of the most sordid works of rock ‘n’ roll pulp semi-fiction. (I mean that as a compliment.)

If I was better-read as a teenager, I would have also been aware of the chapter from Joan Didion’s epochal 1979 essay collection The White Album that witheringly profiles The Doors during the sessions for their third album, 1968’s Waiting For The Sun. Morrison (who is joined at the session by a teenaged girlfriend) comes off as a dim-witted himbo in Didion’s unsparing prose:

Morrison sits down on the leather couch again and leans back. He lights a match. He studies the flame for a while, and very slowly, very deliberately, lowers it to the fly of his black vinyl pants. [Keyboardist Ray] Manzarek watches him. There is the sense that no one is going to leave this room, ever. It will be some weeks before The Doors finish recording this album.

Manzarek later objected to Stone’s film (particularly the scene where a drunken Jim gleefully lights a closet on fire while his girlfriend screams madly inside) as crass and factually dubious exploitation. It was also horrible PR. The very things that boomer-era hagiographers chose to emphasize about the Morrison myth — the self-serious pretension, the heavy-handed pseudo-philosophizing, the frankly assholish behavior — are what fuels a lot of the animus his name inspires today. The caricature that was originally intended to make him look like a tragic hero has instead transformed him into an easily hateable villain.

That portrayal certainly turned me off for a long time. But not anymore. At some point, I realized that loving The Doors is a lot more fun than hating The Doors. If you can manage, I ask that you temporarily suspend your knee-jerk Doors hate and allow me to explain how I broke on through to Jim Morrison’s side.

First, let’s state a simple but weirdly overlooked fact: Even if you dislike Jim Morrison, you probably like the scores of artists he influenced. Iggy Pop has cited Morrison’s vocal style on The Doors’ 1967 self-titled debut as a crucial creative touchstone, while Patti Smith called him one of “our great poets and unique performers.” Ian Curtis of Joy Division, possibly the most seminal singer in the history of post-punk, was another Morrison acolyte who passed down their shared “mournful croon” vocal style down to everyone from Echo And The Bunnymen to Interpol and literally dozens of other punk, alt-rock, indie, and goth bands in between.

The Doors are so foundational in rock that they filter down to artists who either don’t like or even know their music firsthand. Basically any singer in a rock band who dips into a lower register owes something to Jim Morrison. (Glenn Danzig, meet Matt Berninger.) I would go even further and suggest that any group in which a person talk-sings over drone-y music is connected to Morrison and The Doors. To cite just one example, you can hear traces of The Doors’ influence in New Long Leg, the 2021 debut full-length by the acclaimed U.K. post-punk band Dry Cleaning, in which lead singer Florence Shaw talks over tribal guitar licks about how people are strange.

In a 1981 interview, Jerry Garcia dismissed Morrison as a Mick Jagger clone. But as much as I love Garcia, I must object to this reductive take. It’s true that Morrison, like Jagger, adopted a highly sexualized bump ‘n’ grind performance style designed to drive audiences into hysterics. But Jagger was also an emotionally remote cynic who could move freely between participating in the sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll party of the ’60s and ’70s and commenting on it in his lyrics from a remove. There was no such remove for Morrison. He lived out the metaphors in his songs about unlimited excess and all-encompassing doom in his actual real life. Unfortunately, you can’t live like a metaphor in your actual real life, which is why he died.

In that way, Morrison is a lot like Lana Del Rey, another polarizing poet obsessed with death and glamour and messianic posturing and all-American decadence who sings her words in an artless but highly affecting croon. “No one’s gonna take my soul away / I’m living like Jim Morrison,” Del Rey sings in 2012’s “Gods And Monsters,” a title that perfectly captures Morrison’s duality. (I also suspect that all of those really long songs about the apocalypse on Norman Fucking Rockwell were inspired by Del Rey going through a “The End” phase.)

What separates LDR from Jim Morrison is that she had the benefit of learning from Morrison’s mistakes. She knows now that metaphors should be kept in their proper place. Jim Morrison was her rough draft. He was the rough draft for a lot of people.

If I had to distill the current cultural dislike of Jim Morrison down to a single cause, it would be that his very essence as an artist and performer is totally contrary to what is in vogue now. Morrison was highly theatrical and worked almost exclusively in larger-than-life gestures. He sang about setting the night on fire and dancing on fire and lighting your fire. He would carve out a good 20 minutes every night to perform something called “The Celebration Of The Lizard.” Again, he was his own metaphor; he sang about sex and self-destruction and lived a life of sex and self-destruction. He was never a chill, normal dude.

Today’s pop stars are praised for the opposite of this sort of thing. They’re expected to be accessible, relatable, and naturalistic while also being role models. They’re aspirational as ethical figures, which — if you can step outside of current cultural morés for a quick moment — is sort of nuts. Even in his prime, I don’t think anyone looked at Jim Morrison as a good person. That was never even intended to be part of the package. (It should be noted that Jim Morrison was extremely young when he died. How would you be remembered if you were defined forever by your behavior in your mid-20s?)

From the beginning, Jim Morrison was an anti-hero, which partly explains why there were so many waves of Doors revivalism in the years after he died. At every moment in modern history other than right now, anti-heroes have always been awesome. Of course there are many good reasons for anti-heroes being temporarily unfashionable. But it also makes me think that the next generation is poised to react against some of the more puritanical leanings of our time. Because there will be some kind of reaction. (We have not reached ideological perfection in the year 2021, as much as we like to kid ourselves into thinking that.) And then, I wonder, will Jim Morrison be back once again?

Because as much people like to bury Jim Morrison, they also like to dig him back up. Put on a generation-defining movie from the 1980s like Less Than Zero or The Lost Boys and you’ll hear The Doors. In 1993, when The Doors entered the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall Of Fame, they were inducted by that era’s generation-defining rock singer (and another obvious artistic child of Jim Morrison), Eddie Vedder. A few years later, grunge made way for nu-metal at Woodstock 99, but The Doors were still welcome. In 2001, in the wake of Sept. 11, Jay-Z sampled The Doors and Julian Casablancas credited Morrison and co. with making him want to start The Strokes. A decade later, as dubstep took over the culture, Skrillex collaborated with the surviving members of The Doors. Today, whenever I play “Break On Through” in the minivan, my kids know it because that damn song was in Minions.

And you know what? They like that song! And they like it for an obvious reason: Because it’s a jam. It’s fine if you think Jim Morrison is an amoral, obnoxious gasbag. I get that. But can we at least admit that his band did not suck and in fact had many, many jams? “Break On Through,” “Light My Fire,” “End Of The Night,” “The End,” “People Are Strange,” “When The Music’s Over,” “Hello, I Love You,” “Roadhouse Blues,” “Peace Frog,” “L.A. Woman,” “Riders On The Storm” — does anybody else feel like riding the snake right about now? You know that it would be untrue to say no.

The Doors are a Warner Music artist. .