Does any musical act have a greater disparity between the number of words written about them and the number of people who actually got to see them than The Velvet Underground?

Big Star? Possibly, though Alex Chilton was never as famous as Lou Reed. Robert Johnson? Likely, though the iconic bluesman lived during a pre-historic media age. The Velvet Underground, meanwhile, existed in an era of exploding youth culture typified by legendary 1960s rock bands like The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Beach Boys, and The Grateful Dead. In time, the Velvets came to be viewed as one of rock’s most influential and acclaimed bands. But those other luminaries also left behind a wealth of video footage captured during their respective primes that helps us to understand why they’re considered important. For instance, Peter Jackson’s forthcoming three-part Beatles documentary for Disney+, Get Back, is culled from more than 60 hours of unreleased footage. And that’s for the making of an album John Lennon once called the “shittiest load of badly-recorded shit — with a lousy feeling to it — ever.” Even that part of Beatles history is exhaustively documented.

As for the unimpeachable Velvet Underground, precious little live footage is known to exist 50 years after Lou Reed exited the band, which effectively ended their short but illustrious three-year recording career. (Doug Yule’s post-Reed Velvets album from 1973, Squeeze, is an oft-overlooked footnote, and nevertheless feels like something separate.)

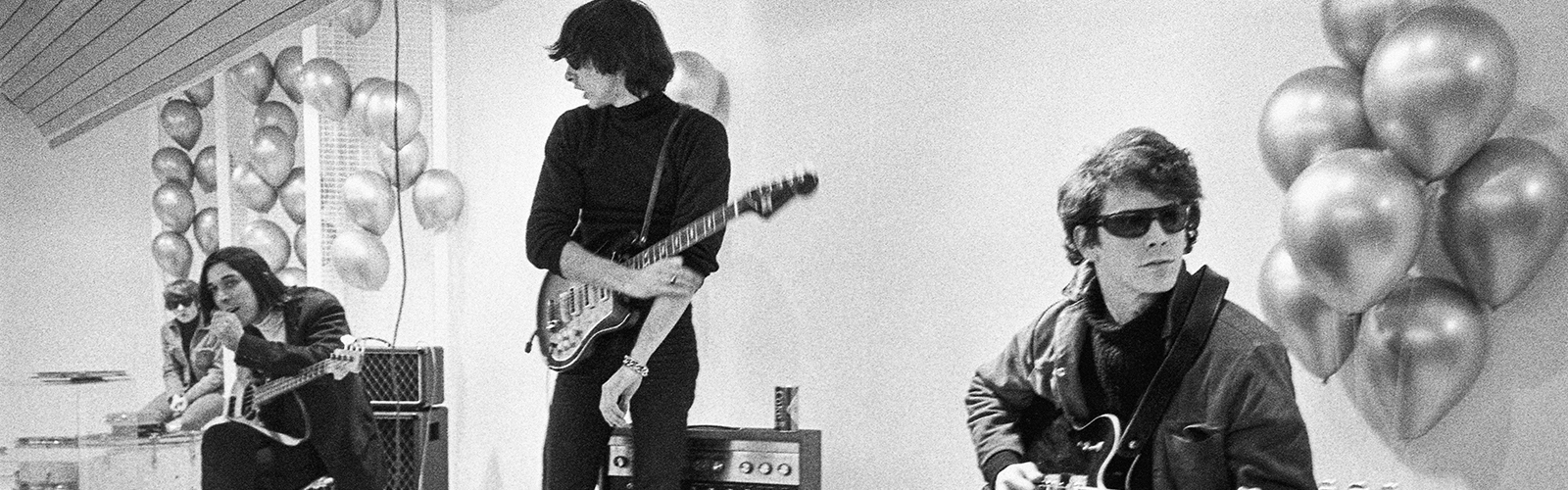

In the late ’60s, the Velvets never appeared on television, and they were never the subject of a concert film. Neither Woodstock nor Altamont wanted them. That’s because they never had actual hits, or much of a public profile outside of a few coastal enclaves. We still have the albums, which sound as menacing and powerful as ever. But so much of what we know about The Velvet Underground is based on the first-hand accounts of those who did see them back then. As for the rest of us, there are frustratingly few chances to witness their grimy glamour for ourselves.

I was reminded of this while watching Todd Haynes’ new documentary, The Velvet Underground, which premieres Friday on Apple TV. Haynes takes great care to place the band in the heady context of the mid-’60s downtown Manhattan art scene, showing how they existed at the crossroads of avant-garde composers such as La Monte Young, whose experiments with drone were pivotal to the Velvets’ early sound, along with the poet (and early Lou Reed mentor) Delmore Schwartz, the experimental filmmaker Jonas Mekas, and of course the pranksterish pop artist Andy Warhol, their most crucial patron. Haynes pulls back even further to depict how Reed’s original obsessions with the city’s seedy underbelly extended from a vibrant local queer community that nurtured writers, musicians, painters, and other artists of all stripes. An island of misfit toys that ended up changing the course of culture forever.

What you don’t see much of in The Velvet Underground — and what separates Haynes’ film from a normal rock doc — is the band actually playing together on stage. There is footage of Reed performing with John Cale and Nico in Paris in 1972, and some quick clips of the original lineup rehearsing or jamming at The Factory. But Haynes is forced to mostly rely on photographs set against muddy-sounding bootlegs recorded at scarcely attended gigs in museums and university student unions, as well as the testimony of onlookers like Warhol “superstar” Mary Woronov who tell us how freaky it was when they played “Heroin” for the first time.

Now, for a lesser filmmaker, this might be a crippling disadvantage. Imagine if Peter Jackson only had, say, 15 minutes of video showing The Beatles at work on Let It Be rather than 240 times that amount. But it actually doesn’t hamper Haynes; in fact, it suits his career-spanning thematic obsessions.

In his previous films about musicians — 1987’s Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story (still only available as a bootleg due to brother Richard Carpenter’s objections), 1998’s Velvet Goldmine, and 2007’s I’m Not There — he was more interested in exploring aesthetics and mythology then doing a dry, journalistic run-through a mundane biography. Each of those movies are really about an “idea” of the subject: Karen Carpenter as a literal children’s doll slowly dying on the inside; David Bowie as an elusive enigma who abandoned his transgressive past for pop glory; Bob Dylan as a constantly shifting facade put on by several different actors. Haynes isn’t trying to tell us who these people “really” are; he’s exploring how we, the audience, perceives them and what this shows about our collective pop-culture illusions and desires.

Unlike those other films, The Velvet Underground is a documentary. But for all of the background details we learn about Reed and John Cale’s upbringings, it’s not really intended to be a full account of the band’s history. The other Velvets are discussed less thoroughly or, in the case of Yule, hardly at all. Once Cale departs three-quarters in, you can feel Haynes’ interest wane. The film ultimately is more invested in what this band signifies: A thriving counterculture that could have only existed at a specific moment in time, and will never be repeated.

For Haynes, The Velvet Underground is like a shooting star whose light didn’t reach the Earth until after it had long since burned out. It’s the ache of loss, and missing out, that the documentary leaves you with. It’s a film about ghosts.

I’m 16 years younger than Haynes, but I suspect we followed similar paths to the Velvet Underground. Growing up as a tween in the ’80s, I first learned about them from R.E.M., who covered several Velvets songs on the 1987 B-side compilation, Dead Letter Office, including “Pale Blue Eyes,” currently their most streamed song on Spotify. Around that time, I went to my local library and read Rolling Stone‘s special “Greatest Albums Of The Last 20 Years” issue, which put The Velvet Underground & Nico at No. 21, between Prince’s Dirty Mind and The Who’s Who’s Next.

What happened next will seem inconceivable to anyone who grew up in a post-internet world: I didn’t hear any Velvet Underground music for another few years. Their albums were not available at the big-box music stores in my town. And none of their songs were played on the radio. I had to imagine what they sounded like based on the R.E.M. covers — which are faithful but nevertheless not Lou Reed — and the Rolling Stone blurb.

Finally, in 1989, Polygram Records issued The Best Of The Velvet Underground: Words And Music By Lou Reed, their first “greatest hits” album in 18 years. This was a time when greatest hits albums could actually be vital historical documents if the original records were out of print or hard to find. The occasion was so momentous it warranted a trend piece in the New York Times trumpeting the band as a bedrock influence on alternative rock. (It was the late ’80s, after all.)

This was also the first VU tape I ever owned. I still remember the off-gray color of the cover, which was emblazoned with a photo that made it look as though Warhol was a member of the band. (For a while, I assumed he played tambourine or something. There was no Google to confirm or disprove this.) It included six songs from the 11-track The Velvet Underground & Nico, and weirdly favored the relative deep cut “Run Run Run” over more obvious choices like the epochal “Venus In Furs” or the luminous “Sunday Morning.” Then again, it’s not as if any of these songs were actual “hits,” so the selections were bound to be arbitrary.

A year or two later, I serendipitously found a copy of their fourth album, 1970’s Loaded, at a used CD store. Loaded includes two of Reed’s most famous songs, “Sweet Jane” and “Rock ‘n’ Roll,” but its status as a full-fledged Velvets album is dubious. Cale was long gone by then, and their utterly singular drummer Maureen Tucker was sidelined during the recording by pregnancy. The journey from The Velvet Underground & Nico to Loaded was still missing some crucial intervening chapters. It wasn’t until the release in 1995 of Peel Slowly And See, a comprehensive box set that includes all four Reed-fronted studio albums, that I was able to even hear 1968’s White Light/White Heat and 1969’s The Velvet Underground, almost a full decade after I first read about them.

All of this is to say, The Velvet Underground for years was a band you had work hard to seek out. The same is true for the downtown New York that The Velvet Underground & Nico vividly mirrors and romanticizes. In the film, we see how small this world was in the ’60s, with numerous movers and shakers living together in small but cheap quarters as they collectively dreamed up a new future. Haynes’ point is that you couldn’t just access this world from the comfort of your phone or laptop. You had to be brave enough, and canny enough, to find it and see it and smell it and touch it.

Haynes has said that the “extinction” of localized scenes in light of the online world’s flattening effect on culture has only intensified his admiration for what existed back then. “You really felt that coexistence and the creative inspiration that was being swapped from medium to medium,” he said in a recent interview. “I crave that today. I don’t know where that is.

In one of the movie’s most eye-raising sequences, an ex-girlfriend of Reed’s talks about how he used to take her to dangerous parts of Harlem when they were in college in order to score drugs. She suggests that these trips had as much to do with scrounging compelling songwriting material as it did with getting high. You can interpret this story as the foolish actions of a deluded wannabe artist. Or you can (as Haynes seems to believe) look at as a testimony to the power and value of in-person experience. Which means, sorry, but if you weren’t there in the flesh at the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, you probably will never see The Velvet Underground. It’s this, after all this time, that still makes them special. Embedded in Haynes’ film is the suggestion that art loses something when it isn’t permitted to be fleeting, and is instead frozen forever in digital amber.

Discovery once was a process that exposed you to a million other tangents along the way. Now, it is an endpoint to which you are delivered — speedily, painlessly, bloodlessly — without anything in the way of effort or sacrifice. It can make even a band as great as The Velvet Underground seem meaningless. Anyone interested in them can easily queue up their albums on any streaming platform and move through the catalog in an afternoon.

This, of course, is a wonderful convenience, and one I would have killed for at the time that I discovered the Velvets. But it also robs this alluringly enigmatic band of their mystery. On Spotify, they really are just another great ’60s rock outfit. Music this exciting and adventurous should require a little more excitement and adventure on the part of the listener to hear it.