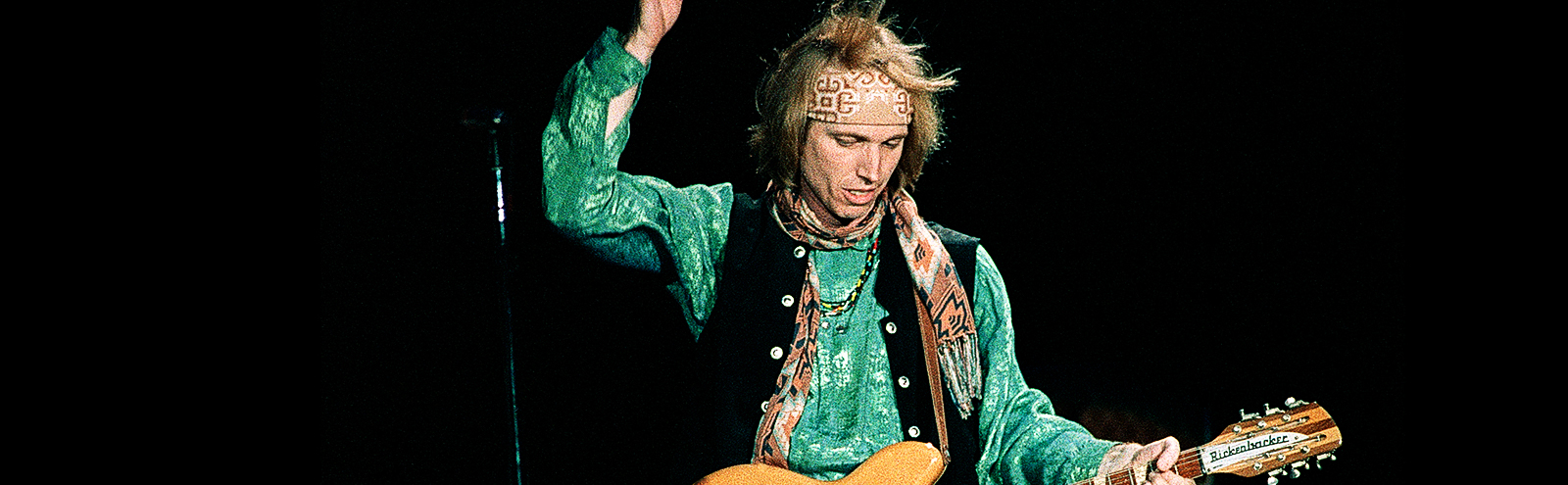

In the final years of his life, Tom Petty had dreams of releasing the ultimate version of Wildflowers, his beloved 1994 triple-platinum-selling album.

If you love the record, you probably know the legend: Petty spent nearly two years making Wildflowers, accumulating enough songs for a double album. But he was persuaded instead to put out a (still expansive) 15-track single LP instead. It’s hard to fault this decision — Wildflowers spawned hits like “You Wreck Me,” “You Don’t Know How It Feels,” and “It’s Good To Be King,” and stands with Full Moon Fever and Damn The Torpedoes as one of Petty’s most popular records. But he knew he had a wealth of strong material that few people had ever heard. So, starting in 2013, Petty began plotting a reimagined reissue of Wildflowers outfitted with the tracks that got left behind.

This collection, called All The Rest, was almost released in the mid-2010s. But Petty held it back. He wanted to keep working on it. Occasionally, however, he would proudly play an unreleased track for a friend or family member. He knew he was sitting on an artistic goldmine.

Petty kept on thinking about Wildflowers during his final tour in 2017, even contemplating a special series of shows in which he would perform the album in its entirety with guest singers. But these plans were not meant to be. One week after the tour concluded in September, Petty died. He was 66.

Fortunately, not even Petty’s passing could hold back Wildflowers. A new box set out Friday, Wildflowers & All The Rest, includes the original album and the 10-song adjunct record that Petty envisioned, plus dozens of good-to-excellent outtakes, acoustic demos, and live tracks.

For fans of Wildflowers, the box set is an essential addition to the record’s legacy. When the sessions began in the summer of 1992 with producer Rick Rubin, Petty had recently turned 40 and was in the midst of a career renaissance sparked by the success of Full Moon Fever. His commercial stature afforded him the time and space, free of record-label meddling, to make exactly the kind of album he wanted. But while he was riding high professionally, he was dealing with fractured relationships in his personal life. His marriage to his first wife, Jane, was falling apart, and he was tiring off the oft-contentious dynamic with long-time Heartbreakers drummer Stan Lynch.

The album then was both a passion project and a refuge for Petty, a place where escape his problems while also examining them via his most personal collection of songs. This “hangout” aspect of Wildflowers’ creation also carries over to the experience of listening to it — if Full Moon Fever is all about the songs, then Wildflowers is all about the vibe (and also many remarkable songs). It’s the kind of album you want to live inside of.

For the people who helped Petty to make it, Wildflowers remains part of the architecture of their own lives. I spoke with three people who were intimately involved in the album’s creation: Mike Campbell and Benmont Tench of The Heartbreakers, and producer/engineer George Drakoulias. This is their story.

Benmont Tench (Heartbreakers keyboardist): I can talk about this stuff all day. I followed Mudcrutch around because I thought they were a great band. I was a fan when I joined. When that band broke up, I was gutted, because I wanted to keep playing with Tom and Mike. Then Tom liked the band I put together for some demos — we had Mike and Stan and Ron [Blair]. It’s like, “Hallelujah, I get to play again with Tom and Mike.” I come from just a fan standpoint and wanting to evangelize the band and to evangelize Tom.

Mike Campbell (Heartbreakers guitarist, Wildflowers co-producer): It seemed like there was a mutual respect and love there. It was just magic and a miracle, really, that it happened. We met each other and we ran down a dream together for 50 years.

George Drakoulias (Wildflowers consultant): Tom would do this old Southern football coach voice: “I’m out here looking for starters. Y’all want to start, you come onto my team.” I don’t want to sit here and say everybody knew it was going to be the most special record of his career. But no matter what was going on, everybody was paying attention. No one was phoning it in. Everybody was focused on the work.

MC: I know a lot of fans tell me that’s their favorite record. So it must be something that connects with people.

In mid-1992, Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers were in a unique position — for the first time in years, they had nothing planned. In the prior three years, Petty had put out two of his most successful albums, 1989’s Full Moon Fever and 1991’s Into The Great Wide Open. After several rounds of tours, he was now settling into an open-ended period when he would have the time and freedom to write and record songs on his own schedule. It would prove to be a pivotal time in Petty’s life and career, starting with his partnership with producer Rick Rubin, who shepherded the remainder of his ’90s output. Sessions for what became Wildflowers commenced in July, but Petty and his band were already tinkering with songs before that.

BT: We recorded four or five of these songs with Stan and Howie [Epstein] at Mike’s house before I knew anything about Rick. I think we recorded versions of “It’s Good To Be King” and “Honey Bee” and “Time to Move On,” at least. I don’t think Tom thought we got the best versions.

MC: It started out like all our records start out. I would get a phone call and Tom would say, “Do you got any music?” I said, “Yeah, I’ll send you over something.” And he said, “I’ve got like three or four songs.” Great, let’s go record them and see what they sound like. And then we had Rick.

BT: I think I knew Rick before Tom and Mike. I was working with Rick on a record, maybe Wandering Spirit with Mick Jagger. And at the end of the day we were outside in the parking lot and Rick said, “Hey, I’m going to produce Tom.” I was like, “That’s a great idea.” Because from the get-go, I loved working with Rick.

MC: He brought a new energy to it and we had to learn to trust his instincts along with ours.

In the early ’90s, Rick Rubin was still most famous for working with rap and metal groups like Run-DMC, Beastie Boys, and Slayer. But he was pivoting to rootsier legacy acts, including Johnny Cash on the first “American” album. Rubin became a Petty acolyte after Full Moon Fever, and then met the singer-songwriter on a cross-country flight from New York City to Los Angeles. Before starting Wildflowers, he enlisted his old Def Jam associate George Drakoulias as a “consultant” on the project. At the time, Drakoulias was himself a successful producer, having steered two multi-platinum albums by The Black Crowes and The Jayhawks’ critically acclaimed breakthrough, Hollywood Town Hall. The sound of the Drakoulias’ records — organic, handmade, live in the studio — points to the aesthetic of Wildflowers.

GD: I think Rick was a little bit intimidated by Tom in the beginning. He met him first on an airplane, but when we went to go talk to him about the record, he dragged me along to Tom’s house in Encino where he was living at the time. It’s funny, back then, 25 years or whatever, I think I was less intimidated, and I would say anything.

BT: I’m telling you, he worked me so hard the first day on Hollywood Town Hall. I came home and I went, “I’m never working with this guy again.”

GD: I mean, Ben is on every track. I think we did everything in two days. I explained to him my philosophy: Take the band as far as it can go and then bring someone in with talent to finish it.

BT: I finished the second day and I was like, give me more, because it’s so good. That Jayhawks record was just so good.

GD: There was a lot of activity going on, because Tom was going to do a greatest hits record and he was going to figure out if he wanted this one to be a solo record. And he was looking for drummers. I think the idea for the record was to keep it handmade, you know what I mean?

BT: I was never not in the fold, so to speak, but they wanted to try a different rhythm section. I don’t know why — maybe just to be fresh, maybe because there was a sound that Tom had in his head or just he thought he’d stir it up. Because at that point we’d been together for at least 20 years. We went to the studio day one and he broke out some songs and there were some drummers that came in and out and we played with them and they were great. Some of them were friends of mine that played just beautifully. But when Steve Ferrone showed up, who I didn’t know yet — Mike did — everybody’s eyes just lit up. That’s the cat.

MC: We had five or six things, and it became clear to us that this was not really a Heartbreakers record. So it became a solo record at that point. It was very casual and it was all about the songs.

BT: We made the record with Ferrone never intending for Stan to leave the band. Just like Full Moon Fever, most of it is Phil Jones on the drums, but Stan played “Free Fallin'” 200 different times on the road.

In terms of sound and process, Wildflowers is a decisive departure from the two albums that precede it. Working with Jeff Lynne, Petty relied heavily on overdubs for Full Moon Fever and Into The Great Wide Open. But for Wildflowers, he wanted the musicians to play together again in the studio. That meant relying on most of the Heartbreakers, even if this was technically a “solo” record.

MC: I love the Jeff Lynne records and I would make one with him tomorrow if he wanted to. Such a wonderful guy to work with. And his process is so together and fast and creative. But we did two records with him.

GD: Wildflowers is more of an acoustic-based record. Even though Full Moon Fever was an acoustic-based record, those acoustics are stacked and layered. It’s more like a sound than an individual playing. It becomes a wash, which is great. You know, I love Full Moon Fever.

BT: I’m not on much on the previous two albums. I’m on “The Apartment Song” on Full Moon Fever, and I play a little bit on Into the Great Wide Open. But that was mostly Tom and Mike and Stan and Jeff. And I think Howie and I came in in different places where we were needed because all those guys could play piano and if they have a good hook, they’re going to do it.

MC: We just thought in the back of our minds, it’d be nice to play live again in the studio, and go back to that approach of how we started. And then Rick Rubin showed up and he liked doing records that way, too.

BT: If you build a track [with overdubs], something is static and cannot change. At a certain point, there is not going to be a surprise. Nobody’s going to make an accident that’s better than the idea they had in the first place. I love the conversational aspect of music. I really love it.

One of Tom Petty’s gifts as a songwriter was the ability to come up with fully formed songs extemporaneously. The greatest example of this is the title track from Wildflowers, which he wrote off the top of his head while recording the demo at home. The song spoke to Petty’s frayed state of mind over his failing marriage, and his desire to finally break free. But Petty made up other really good songs, too.

BT: He’d just do it in soundchecks. Or he’d do it while we were recording between other songs.

MC: He used to walk up to the mic and maybe sing a line, and then we would go, “That sounds interesting.” And then he’d sing the next line, which had this really clever rhyme. And he would just channel it right on the spot. I’ve never really seen anybody do that quite like that. It was a special talent he had.

BT: If you’re a songwriter, that can happen. It’s just that it isn’t usually “Wildflowers.”

MC: “Girl On LSD” [a beloved Wildflowers era B-side] is like that. I don’t think he even had any of the lyrics. He just kind of saw it in his head and made it up on the spot.

The process of recording Wildflowers followed a pattern: Petty would bring a song in to the band, and if the room responded well the musicians would instinctively add their own parts. This was especially true of Campbell and Tench, his best and most loyal sidemen, who are such a crucial part of his sound that they might as well be his right and left hands. When it came to the song “Wildflowers,” Tench hit upon a stunning piano lick that perfectly accented Petty’s vocal at the end of the track. It’s one of the album’s best moments.

BT: We played “Wildflowers” and I knew I wanted to play that lick at the end of the song. I practiced because when Steve came in, he’s a really precise guy. You can time him with a stopwatch. My whole life I’ve played music with different people with the kind of feel that Stan plays. Steve comes in, I’m like, holy moly, I got to find a way to play so that it fits with this guy’s feel. I was home practicing with a metronome, because I loved this part and I wanted to play it really well. I think it’s from my lifelong obsession with banjo, because that piano figure is almost like a banjo figure.

GD: They’re just a fantastic American rock band. This might be a case where the sum is as equal as the parts. Because each guy has gone on to do great things. Mike’s written amazing songs and had hits with Don Henley. And Ben’s played on thousands of records and brings his thing. As a band, they’re incredible.

BT: We would just play. If he wrote the song on a keyboard, he showed me the way he wrote it and asked me to pretty much to play that. But in general, with everybody, he’d just see what you’re going to do because that’s why you have a band.

MC: I don’t want to compare Tom and I to them per se, but it’s a very Keith and Mick relationship. I could bring music to him that he might not think of because typically when he wrote on his own, it would be jangly country strumming, which is great. But sometimes I would bring him tracks with a different approach, bluesy or whatever. I think he liked that I had a well of different music. At the same time, we had the exact same influences. So we were kindred spirits, musically. As soon as we met, it’s like, wow, you’re just like me.

BT: We were all on the same page from the get-go, from the time I saw Mudcrutch. I think McCartney said that when Ringo came in, they were like, “Holy shit!” Because when the right people play together, it’s not work. It happens.

MC: It’s mostly intuition. I think that’s why Tom liked me. I could sit down with him as he showed me the song and start playing along, not knowing where the song was going necessarily, but just intuitively filling in the right holes, making him sound better and following the direction he wanted to go. That was just a natural thing that we always had. That’s why 95 percent of the guitar parts on the records are off the top of my head. They’re not orchestrated are written out at the beginning. We never really worked that way. You just go in the moment and something happens and we always seemed to agree on what helped a song.

GD: An average Tom song, once the band got a hold of it, would sound like the best song of an average band. It was like all of a sudden it would exceed your expectations. They would bring their taste and their skill to it. It was a blessing and a curse, in a way.

One pretty good Tom Petty song that is elevated to excellence by the band on Wildflowers is “A Higher Place.” The track ends with a majestic guitar solo by Campbell, who made a habit of wrapping up Tom Petty songs with majestic solos — everything from “American Girl” to “Even The Losers” to “Don’t Come Around Here No More” to “Runnin’ Down A Dream” to “Mary Jane’s Last Dance.”

MC: I think that comes from the music I grew up on, with The Beatles, The Stones, The Beach Boys, The Kinks, The Animals. I’ve just loved the way those guitars worked within the song. It wasn’t about ripping a solo or showing off how fast you could play. It was coming up with something that really complimented the song and help the voice along. That’s the way I try to play. But I also liked to play out. I like Mike Bloomfield a lot and Clapton and Hendrix, but a lot of Heartbreakers songs aren’t in that mold. But occasionally there would be a spot at the end where there’s no vocal. You can go anywhere you want. So in those few places, I would explore a little more of the lead guitar stuff, but within a song I like to just fit in like George Harrison.

BT: I don’t know if you call it telepathy, but Michael Campbell and I, there’s an interlocking thing. Or just giving each other room, and knowing when somebody is going to play. It’s a great joy in my life to do that with Mike.

MC: We found a way instinctively to compliment each other with our tones and our parts. Tom would show us a song, and Benmont would do what came to his mind, I would hear that, and see what came to my mind. He might hear, “Oh, Mike’s going there” and he’ll answer. We were able to find a tonality between my guitar and his keyboards that made a sound. It was kind of unique to us.

As producer, Rick Rubin stayed focused on the essentials — keeping the band tight and no-frills, and encouraging Petty to come up with the best material.

BT: On some songs, he’d kind of program Steve. He’d be like, no, don’t play any cymbals. Can you go, boom, boom, flat here?

MC: I wrote the music for “You Wreck Me” at home. I was probably thinking about Bo Diddley, something upbeat and exuberant feeling. I got the chorus and structure together and gave it to Tom, on a tape with a bunch of other ideas. About a week later, he said, “I liked that, we could do something with that.” Later I said, “Have you done anything with it?” He said, “Well, you know, I don’t know, it’s in a drawer somewhere” and it got forgotten.

Later, Rick asked, “Do you have any songs?” And I said, I gave him one, but he didn’t ever do anything with it. I played it for Rick and he goes, “That’s great, I’ll go tell him to do it again.” So Rick presented it to him again and he acted like he didn’t even remember it. But he did write to it. And it did come out really good.

BT: At the end of “It’s Good To Be King,” I started playing this repetitive figure and after like six bars or something I moved off of it. Rick went, “No, no, no, you play that figure all the way to the end.” That’s the reason I love Rick.

GD: We used to love “It’s Good To Be King.” We just thought the lyrics were so much fun, and we’d quote them. “To be there in velvet” was just a great line. A lot of the lyrics became part of the lexicon of what we were doing in studio. “I’ll be the boy in the corduroy pants.”

The sessions for Wildflowers stretched from the summer of 1992 to the spring of 1994, a nearly two-year process that was far longer than the typical Tom Petty record. He wanted to take his time to make the best possible album, but he also loved being in the studio. The clubhouse-like environment of Wildflowers was a refuge during a difficult time.

MC: The thing to remember is there’s a lot of songs, but they were split over two years.

GD: We spent two years to make it sound like it was recorded in a weekend. That’s a skill.

BT: There wasn’t any pressure. I don’t think that there was a tour lined up, and I never heard about a hard finish date. It took 18 months, but we weren’t in there all that time.

GD: I think we took four days to overdub one bass part. No one was standing over anybody’s shoulder going, “You got to deliver this thing now.”

BT: We would record a bunch of songs he had and take a break and then we’d get the call to come back a month or however much later. We’d go in and Tom would have the songs. He and Mike might’ve had a notion about how to do them, but most of the time he just showed to us on guitar and on piano and we’d play it.

GD: It was kind of a problem-free zone. I mean, you can tell some of the lyrics are pretty heavy-duty and hard, but we didn’t sit there and analyze them. There were no group hugs, really. It’s fitting that we would stop the sessions on Thursday nights to watch Seinfeld. What was their thing? “No hugging, no learning.”

MC: We would record for a week, maybe two, and then maybe take a month off and just wait for new songs to come in. So in a way it was prolific, but in a way, it wasn’t. There was time to wait for the songs.

BT: The length of time wasn’t because we were slaving over it and couldn’t get the takes right. Everything came really quickly. It was a lot of fun to make the record.

GD: It became like a frat house, in a good way. Or a clubhouse. I like to call them lifestyle records — you get up in the morning and you take your shower and have a little breakfast. Then you head over to the studio, discuss what you’re going. And that was what your day was going to be.

MC: Some of these songs were in the early writing phase, and then you would live with them for a while and he’d come back and go. “I don’t like that, I got something better.” And we just kept refining it.

GD: “Don’t Fade On Me,” that was — not a difficult one — but a lot of work and care went into it. It was recorded several times in several set-ups. It was finally done at Mike’s house, just Tom and Mike playing to each other acoustically.

BT: Then Ringo shows up. I knew Ringo a little, but to have him come play with us, that was so cool. He was in The Beatles, which means he was a Beatle-quality drummer.

GD: There’s stuff like “Cabin Down Below” that was a lot of fun. We’d dance in the control room.

MC: On “You Wreck Me,” he couldn’t get the chorus quite right. And he just kept coming in and changing it and waiting for a better idea to come in. He was like that — he wouldn’t always settle with the first thing. He would live with it and improve on it as time went on.

GD: One of my favorite things is Tom’s sense of humor and just his joyful way of living. He would laugh and his whole body, literally from his toes, would just get into it. If I told him a good joke it was as good as writing a good song.

BT: There are parts of it I don’t remember recording. They sent me a copy of a test pressing and “Crawling Back To You” came on. It’s like, I’m having an out of body experience. I don’t remember recording that! And you know what? I was stone-colds sober for five years when we started the record and I’m 32 years now. It wasn’t that I was drug-addled. We were working hard. Slowly it came back, but we recorded so many songs.

So many songs, in fact, that Wildflowers was originally conceived as a double album, But Petty was persuaded by his record label, Warner Bros., to pare back to to a single 15-song record.

MC: I have no regrets about that at all. I liked the original record the way it came out and I knew eventually the other songs we’d find a home. And I thought it was probably more effective than putting out a double album at that time on a new label. It was probably a better statement just to take the best stuff and stick it on one record.

BT: I don’t think anybody made Tom do it because nobody ever made Tom do anything. It’s a hell of a lot of songs as a single CD. As a single CD, it’s probably as long as a double LP and maybe as long as The White Album. Would you have wanted “Something Could Happen” to get lost in the shuffle? I wouldn’t. I remember cutting that. We cut it with Stan and Howie, and then I think we cut it again with Steve. The one that’s on the [box set] is the one we cut with Stan and Howie, and I just loved it when Tom showed it to me. I loved the groove. I didn’t really understand why it was just put aside. At the time I got the impression that they didn’t think that we got a good take of it. But I listen to it now and I’m like, “I knew it was a good take.” I’m so glad that that song’s seeing the light of day.

In the process of assembling the new box set with producer Ryan Ulyate and Petty’s daughter Adria, the musicians rediscovered scores of songs that they hadn’t heard in more than 25 years.

BT: There’s so much stuff. Jane or Adria found some demos. Ryan would go, “Do you remember recording this?” And he’d play us something that we hadn’t heard since 1993 or ’94 and it’d be like, “Well, damn, that’s just beautiful. Yeah. I remember that. That’s the one that sounds like the Buffalo Springfield.” It was just a beautiful sense of discovery.

MC: I like “Something Could Happen,” I think that’s really good, and “Hope You Never,” which might have been released before on something. [It came out originally on 1996’s She’s The One—ed.] There’s an alternate take of “Wake Up Time,” that’s really good. And an alternate take of “Don’t Fade On Me” that I really like.

BT: There was a song that I had never heard before, “Harry Green,” which is a really beautiful song.

MC: I remember hearing it, but I think it was probably in a batch of other songs and we passed over that to work on the other songs. So it was very vague to me. But you know, it’s basically just Tom and a guitar and a story. He was really good at that.

BT: I don’t remember hearing “There Goes Angela.” Mike does, but I don’t remember hearing it at all because I would’ve been going, “Hey, we got to cut that!” We never cut it with the band.

GD: When I heard that, I was like, “Oh my God, Tom. Really? Why were you hiding that?”

MC: I remember “Leave Virginia Alone” well. It’s a very Tom song — his rhythm, his style on the guitar, and it’s very identifiable. It’s the way he writes. I know it was shipped off to Rod Stewart at one point and I can’t really speak for Tom, but maybe he figured if he was going to ship it out, that he would hold our version back till later.

The Wildflowers box set arrives just over three years after Petty’s passing. Listening to these songs for those closest to him can still be difficult.

MC: There were times when I would just say, “I really can’t do this right now,” because I couldn’t handle hearing his voice and knowing he wasn’t there. So I dealt with that, but we got through it.

GD: The acoustic demos on the box set are really fantastic. They’re really beautiful and intimate. Now it just makes me miss him more.

MC: It’s exciting to hear the stuff, that it’s good, that we can now put out and share with everybody. And I enjoyed going through the archives and hearing everything. I love the record.

BT: Mostly, it’s really, really happy. I love this band, we were so good. It was such a joy to play in The Heartbreakers and to play with Tom. Wildflowers was an extension of that.

All Heartbreakers fans are wondering: Will this band ever play together again? Nobody can say either way for now. But Campbell and Tench both say they still consider themselves members of Tom Petty’s band.

MC: I’m the co-captain. And I love those guys. I’m still in the band. Tom’s just not there.

BT: We’re family. It’s blood. You keep a band together that long because you love each other. We might get really mad at each other, but I don’t think anybody ever hit anybody. Oh, maybe Ron and Stan one time in a hotel hallway in 1977. But mad as anybody might be, nobody could go anywhere because it’s family.

MC: We’re still grieving. We have to grow through our grief to a point where we can all be in the same room and try to make music without our captain there. That’s going to take a while. It just doesn’t feel right yet to me.

BT: He was a really gifted man, and he was funny as hell. And he was a great rock ‘n’ roller. Everything he sang was real. Pretty cool for a kid from Gainesville, Florida.

Wildflowers & All The Rest is out Friday via Warner Records. Get it here.

Tom Petty is a Warner Music artist. .