South Dakota is an objectively beautiful corner of America. The seas of green grass that undulate in the wind, the ancient towers of the Black Hills, and the mysterious colors of the Badlands all add up to something truly special. Yet South Dakota — like so many significant slices of our nation — is not all beauty without consequence. It contains multitudes, many of them painful. A tragic chapter of American history and the still reverberating aftereffects of that chapter are tucked away on Indigenous lands like the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. For many travelers, this painful legacy is reason enough to avoid the area; instead, this should be part of the motivation to visit.

It’s seldom said outright, but sometimes travel isn’t about blissed out beaches and Instagram dreams. Sometimes it’s about confronting a harrowing reality that’s all too easy to ignore. That’s what makes travel of the boundary-pushing variety so mind-expanding for poets and vagabonds across history. It’s not the food or the architecture that blow our minds, it’s the expansion of our own empathy.

This is why you need to go to South Dakota. Why you need to visit the Crazy Horse Memorial. Why you need to witness how two disparate cultures have come together to heal, even as the massive rift between America’s Indigenous population and colonialist aggressors continues to widen. The white and Indigenous families working together at Crazy Horse are creating a bridge between communities, empathy between onetime enemies, and a large-scale testament to how great America can be when we reach out to each other. The memorial, which deserves to be every bit iconic as those other faces carved into rock in the state, stands as a beckon of hope. A hope that history will be told. A hope that justice may one day be served. And a hope that life on the Pine Ridge — and a too long list of other Indian Reservations — will one day get better.

Life on the Rez

The Pine Ridge Indian Reservation is still officially designated as Prisoner of War Camp #344, according to the US Government. Life expectancy is lower than Iraq, Sudan, and Yemen. Suicide rates are the highest in America, with children as young as 12 electing to end their lives. Alcoholism and drug abuse are the highest in the country. Sexual abuse is rampant — most of it is perpetrated by non-Natives. 97 percent of the people on Pine Ridge live below the poverty line and up to 95 percent are unemployed, depending on the season. Being an “Indian” on the Pine Ridge — and in America in general — also means you’re the most likely to die at the hands of the police.

Traversing the Pine Ridge lays all of this bare. Life feels arrested. The very real suffering of Americans stops being an abstract state in the New York Times or on a PBS documentary. And finding “the why” of this prolonged pain doesn’t require a particularly lengthy excavation. A trip to the Oglala College Historical Center lays out the history of the Lakota’s experience with the US government in agonizing detail.

The Lakota of South Dakota have spent the better part of the last 200 years fighting for religious and cultural freedom, their sacred lands, and what was promised them in the treaties signed with the United States. They’re fighting daily for the security, housing, food, education, and health care promised to them in treaties with the United States. Many are still fighting to be recognized by a conquering government. And, the Lakota are still fighting to get back the Black Hills — a place of deep sanctity — that was ripped from them illegally and then scarred with the faces of the perpetrators of their demise.

Why are the Black Hills so important?

For at least eleven millennia, the mountainous area in the Southwest quadrant of the state has served as a holy land to the people of the Great Plains. The Lakota secured the land in the Treaty of Fort Laramie, in 1868. That treaty guaranteed all of present-day South Dakota, west of the Missouri River, to the tribes forever.

Unfortunately, the United States had zero intention of upholding that treaty. When gold was discovered, colonist prospectors flooded into the Black Hills — again, the most sacred land of the Lakota. They brought with them disease and great strains on an already strained food system. This led to fights between colonists and the Lakota which, in turn, led to the US Army sending troops to exterminate the Indigenous population.

Lakota chiefs like Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, and Red Cloud railed against the United States and won a series of battles. The US government’s inability to successfully fight a guerilla war caused them to change their tactics. The Army and colonists started attacking the people’s food source: The buffalo, elk, deer, and birds of the plains. The US Army starved the people until even Crazy Horse had to surrender. By 1877, the Lakota lost (through subterfuge) huge swaths of the land promised to them in 1868.

Years of starvation and disease ensued on the reservations and culminated with yet another massacre in 1890. This time it was at Wounded Knee. The reason for this killing? People were dancing and praying for salvation from an apocalypse. At least 300 unarmed men, women, and children were mowed down by guns (though it was likely closer to 500 people). The American soldiers at Wounded Knee are still the most decorated troops in US military history, with 20 Medals of Honor.

The “Other” Memorial

With further land grabs happening in 1889, 1910, the 1930s, and during WWII, the Lakota tribes of South Dakota ended up with what’s now the Rosebud and Pine Ridge Indian Reservations in the south, Crow Creek along the Missouri River, and the Cheyenne and Standing Rock Indian Reservations in the north of the state. They had lost the Black Hills.

With no other recourse, the Lakota went to the nation’s courts to get their sacred Black Hills back. It took nearly a century before the US Supreme Court decided in the favor of the US Government in 1980. However, the court did declare that the Black Hills had been illegally annexed by the U.S. government and offered the Lakota monetary compensation for the land. The Lakota refused the payout since a land that sacred is literally, in every way, priceless.

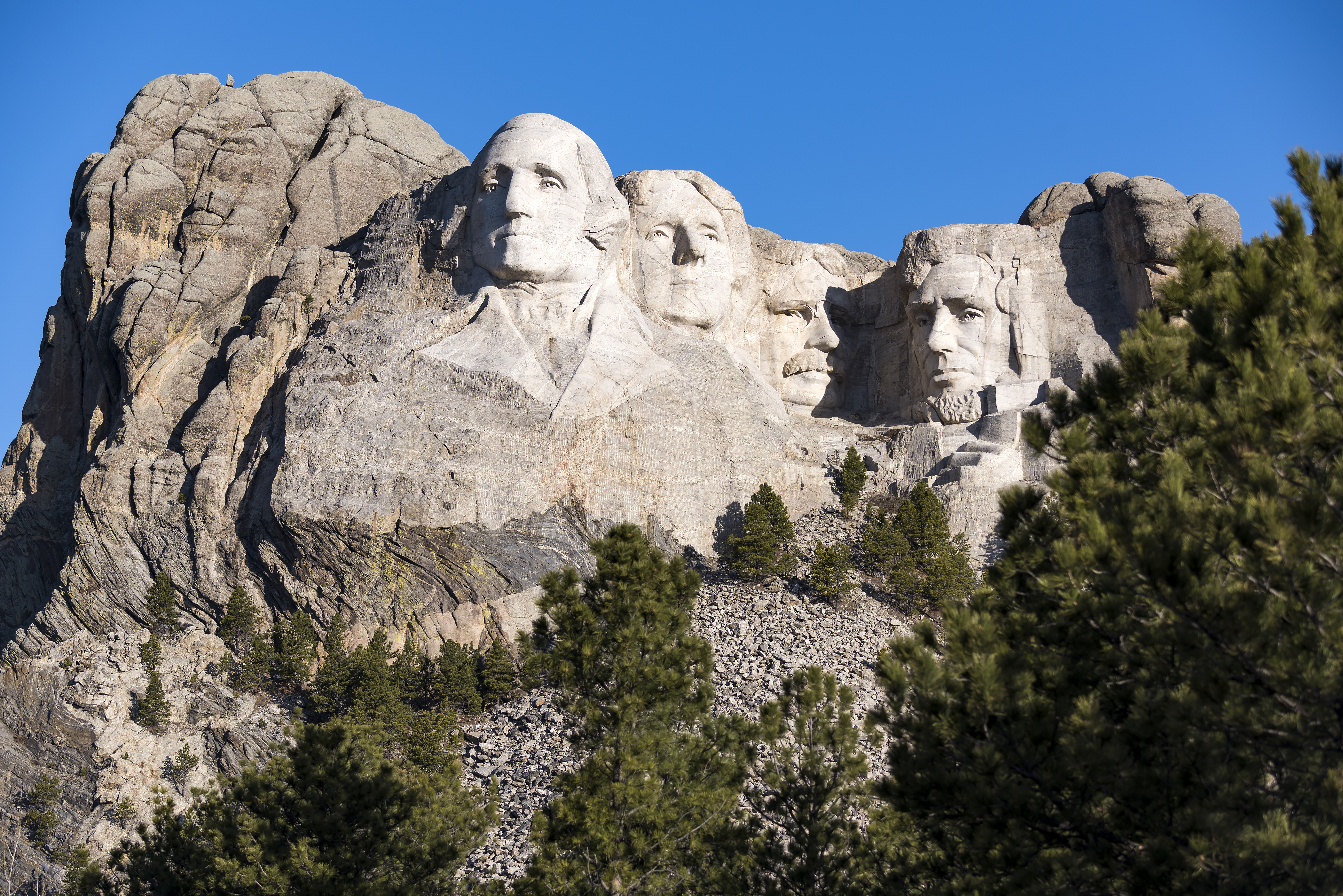

To add insult to injury, during that nearly 100-year-long litigation, the US government started carving a monument on one of the most sacred mountains in the Black Hills, Tunkasila Sakpe (loosely translated as the Six Grandfathers). In 1927, the mountain that had been renamed Mount Rushmore was chosen by the avowed bigot and anti-semite Gutzon Borglum to become a monument to promote tourism to South Dakota. What made it even more painful was the choice of subjects: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Teddy Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln. This was a brutal slap in the face to the Lakota and Indigenous people in general.

For non-Indigenous Americans these men are heroes. For Indigenous Americans, these were our greatest enemies (I don’t write those words lightly):

- George Washington’s record on American Indians is literally genocidal. He ordered the Sullivan Expedition which destroyed 40 Iroquois towns and sent over 5,000 refugees out of what is now New York state into Ontario. In Indian Country, George Washington’s nickname is “Destroyer of Cities.”

- Thomas Jefferson called for the “extermination” of the Indigenous peoples of America — his word, not ours — and funded the westward expansion to facilitate that extermination. That was a national mandate until President Ulysses S. Grant decided to end the “war of extermination” because it was too expensive and replaced is with assimilation (which created a whole new mess of problems, like kidnapping generations of children).

- Teddy Roosevelt, a eugenicist, famously said: “the only good Indian is a dead Indian.” He also took away treaty promised unused federal lands from the Indian population and turned them into national parks, further denying people access to their promised lands. Roosevelt also signed an executive order to flood Indian Reservations with alcohol to speed Indigenous people’s demise.

- Finally, Abraham Lincoln is responsible for the horrors of Sand Creek — a massacre that spared no chance to beat infants to death and rape women in front of their daughters. He also made all Indian criminals by reclassifying Indigenous acts of war as crimes. This allowed the US government to legally enslave, imprison, and mass-execute any “Indian” they wanted to. If we’re piling it on, Lincoln also ordered Navajo Long Walk which killed 94 percent of the adult population of that community.

The barbarity of these men towards Indigenous Americans is massive and, as an Indian in America, you have to live with that reality daily. To see their faces etched into the Black Hills makes the pain even more potent. Of course, no one learns any of that at Mount Rushmore. At Mount Rushmore, it’s all flags and Thomas Jefferson’s ice cream.

Hope Rises from the Stone

This is still America and, in America, a voice can bubble to the surface to challenge the status quo and hold a mirror up to injustice. 15 short miles from Mount Rushmore is that mirror. For three generations now, people have been working to create the biggest sculpture of a human on the planet, as a direct counterpoint to Mount Rushmore. Chief Henry Standing Bear commissioned Polish-American sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski to create the memorial after an introductory letter in 1938. Chief Standing Bear’s reasons were simple. He wanted the Black Hills, of all places, to recognize a local hero and chose someone who he felt embodied the spirit of the land. “Crazy Horse is a real patriot,” he said, originally campaigning to have his face on Mount Rushmore next to Washington.

In the early years, Chief Standing Bear pleaded through letters directly to Rushmore’s sculptor, Borglum to have an Indigenous hero added to the site. After years of being ignored, Chief Standing Bear found Ziolkowski — who spent years with the Lakota on Pine Ridge. Work on a monument to the last great chief finally started in 1947 and continues to this day. That work has been carried out for 71 years without federal or state funding. You can donate to the building of Crazy Horse here.

The vision at this site has expanded over the decades. The site now includes a museum of the North American Indian, a cultural center, and Native American college. All of this has the backdrop of the great chief high up on the mountain. It’s part sanctuary, part historical correction and part promise to future generations of Native kids.

To this day, the Ziolkowski children and grandchildren toil on the mountain whittling away the rock and run the operations of the whole center, along with tribal leaders from the area. The collaboration is a humbling devotion to telling the other side of history and offers a glimpse into how great American can be. Not for nothing, but they make a pretty mean Indian Taco at the visitors center too.

***

Let’s look at this from a more personal angle for a moment. The last time I was in South Dakota, a journalist asked me a very pertinent question. “What, if anything, do you think Native Americans share culturally across the country?”

This is a good question. I thought for a moment and replied. “Trauma.”

Our cultures are too diverse for any real common thread. The difference between the Salish and Hawaiian cultures I come from compared to, say, the Seminole of Florida are as divergent as the Irish and Iranians. The trauma, however, is universal.

We’ve lived through families being torn apart, the wanton destruction and illegalization of our language, religions, and culture. The stealing of our land historically and in the present day. We all live with continued dehumanization every single day of our lives. This truth is self-evident and seen by simply walking around the Pine Ridge and seeing the loss and trauma still plaguing the people after 150 years of living at Prisoner of War Camp #344. Do you want to help us all heal? Then go to Pine Ridge. Connect with people. Spend your tourist dollars in a corner of America that needs it, quite literally, the most. That’s part of what makes travel to South Dakota a crucial step for every American.

For me, a trip to South Dakota is about history. But history has a consequence and those real-life consequences are unfolding right now for Americans who the general population all too often literally forget exist. Recent polls show that 40 percent of Americans no longer believe that Native Americans, or Indians, or whatever you decide to call us next, exist.

This is why traveling to South Dakota is so important right now. Go to the Pine Ridge and see what vitriolic words, draconian policies, and dehumanization of Indigenous peoples does to real, living human beings. Then take a moment to absorb the museum and monument at the Crazy Horse Memorial. The lessons necessary to be better Americans — humans even — are right there on the surface, chiseled into the stone.

Visit here for Uproxx’s press trip & hosting policy.