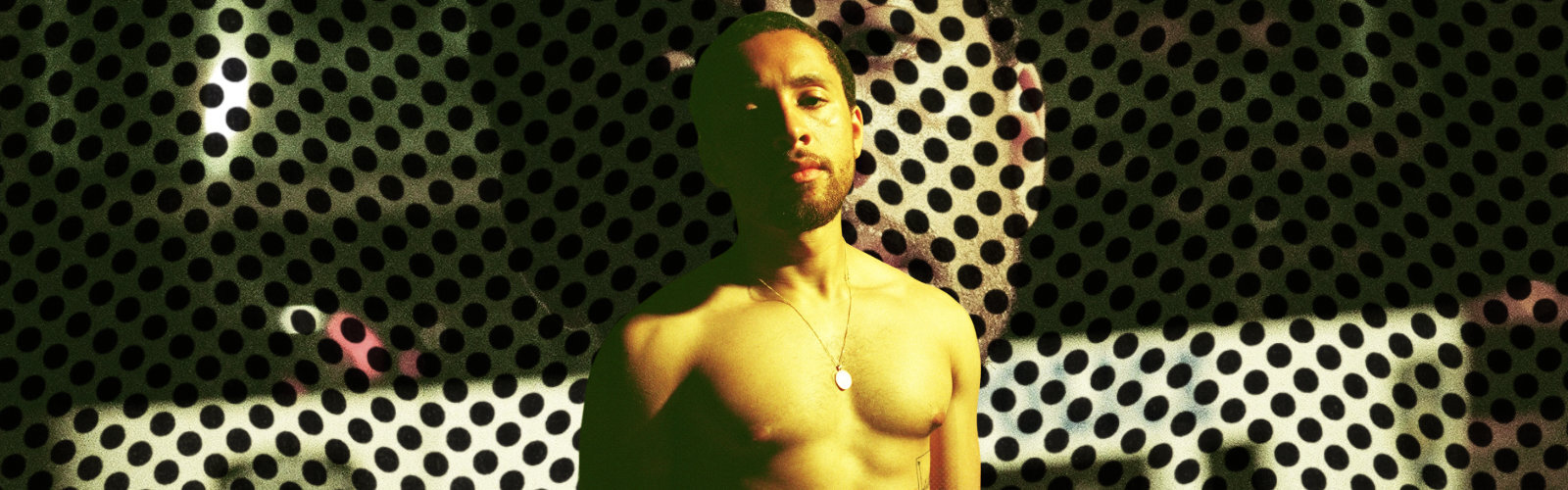

You may have noticed, over the past several months, that more of your favorite standup comics are dipping their toes into music. Jaboukie Young-White certainly has, and he’s got a great explanation for it: “I also think that the very stringent, ‘Oh, you do this one thing, you can’t do this other thing’ — that just doesn’t feel like a Black thing to me,” he tells me during an enlightening (and yes, hilarious) Zoom call. We are discussing — what else? — Jaboukie’s new album, All Who Can’t Hear Must Feel, which is out today via Interscope.

The eclectic project takes inspiration from the experimental, avant-garde rap of acts like 454, Azealia Banks, and Jpegmafia, as well as electronic dance music influences. Jaboukie started putting it together during the live entertainment shutdown of 2020, and its title comes from a proverb often uttered by Jamaican parents as a warning. If you can’t learn from instruction, you’ll learn from bitter experience; as a stand-up, artist, and activist, Jaboukie’s experience is extensive.

The comedian, who often challenges and interrogates ideas of identity, masculinity, and sexuality in his standup, leans into the subjects here, but don’t get it twisted; this is not “conscious rap” or rap with an overt message. Over the course of the album’s 13 tracks, Jaboukie explores these themes in depth, but he also gets loose, indulging his inner hip-hop head and encouraging listeners to shake off their blues, as early house raves once did.

Over the course of our conversation, we touch on these subjects and more as we collaborate to unearth the truths behind its creation, the hope for its impact, and the correlation between being funny and having bars. While subjects like his role in the HBO hip-hop dramedy Rap Sh!t were off-limits due to the ongoing WGA and SAG strikes against the AMPTP, church plays, politicians, and even a passing familial resemblance were all on the table.

I gotta say: Normally I do not really like avant-garde, stream-of-consciousness hip-hop albums. But this one, it grabbed me by the neck. There was a bar on there that cracked me up, and I highlighted it. When you were like, “They say Bouks, he be snapping in the booth / I say, ‘True. What’s another enclosed room?'” And I’m mad at you. That was a good-ass line.

Thank you, man. I’m glad that you pointed out that one. There’s some in there where the real hip-hop head came out in me, where I’m like, people who are casually listening are not going to be getting this, but the people who will read lyrics, this is for those kinds of people. So, I’m happy that you liked it. I appreciate that.

You’d been working on some demos in your spare time. How exactly did those get into the hands of (Interscope CEO) John Janick?

I was working on a Juice WRLD film. It wasn’t his biography, but it was going to be based on his music. So I’m working on that, and it would’ve been potentially the first animated feature that I would direct, and I didn’t have a studded-out resume. And it wouldn’t just be me. It would’ve been me and other co-directors. But then they’re like, “Okay, well, do you have music experience? That would be a selling point for you as a potential director.” And I was like, “Yeah, I got a little something.”

Then I sent along a SoundCloud link with a few songs on there. I think it was “26,” “Incel,” an early version of “Hit Clips,” and maybe an earlier cut of “BBC.” And I sent those out, didn’t hear anything. A week goes by, still don’t hear anything. Maybe two weeks go by and I’m like, okay, I’m just going to close that and I’m just going to pretend like that never happened. I was like ‘Alright, that’s in the past. We’re moving on. New thing, new me. Forget about it.’

And then maybe a few more weeks go by, or at least what felt like a few more weeks. It could have been days. I don’t know. That was my first time sharing music with literally anyone other than my brothers and maybe a few close friends. So I’d never done that before. And then I get a frantic call sometime later and someone’s like, “Open the link, open the SoundCloud link, open the SoundCloud link.”

And then I hear from the guy that they passed it to, John Janick. He liked it and then wanted to meet with me. So I met with him and then they were like, “Yeah, do you want to do this for real?” And I was like, “Yes.” And I really forced my way into it. That’s what I’ve been saying. But it really did feel like I kind of just happily stumbled into a great opportunity.

It feels like that’s how all the best stories go, right? It’s just “something happens and then something else happens and then the next thing you know, there you are.”

Right. I just was lucky enough to, when that question was asked, be able to say, “Yeah, I got something,” and was able to share it. I feel like that’s how every single lick that I’ve hit has always been luck. It wasn’t a lick. It was luck. It wasn’t a finesse. It was like fortune came and then I just so happened to be ready when it happened.

That’s the title of the memoir. It Wasn’t a Lick, It Was Luck.

It wasn’t a lick. It was luck. Yes.

When and how did you get started? Because obviously, we all downloaded a DAW at some point in our lives. I had an early, early version of Fruity Loops I stole online. Where did you get started? How did you get started? Who helped you? What were your early experiments like?

In fourth grade, I played the trumpet for a few months, but it was way too loud, so I couldn’t really practice. Then I asked my dad for a guitar when I was in seventh grade because I was really into Arctic Monkeys and Fall Out Boy. He got me this busted-ass ukulele from the flea market and was like, “If you could learn to play on this, then you could learn to play a guitar.” And I was like, “Okay. No.” So, my thing was: I was always obsessed with lyrics. That was a part of the reason why I love Fall Out Boy so much. There’s so many bars in Fall Out Boy songs. Shout out my Jamaican cousin, Pete Wentz.

Listen! Black people, we out here, the real light skins, we out here, we got bars.

Right, exactly. So there’s that. And then also [Lil] Wayne’s run from 2005 to 2012 was…

Legendary.

Yes. He was saying things that no one had said before in the history of the English language, just combining words in a way that was so novel, so crazy, so genius. So I was writing stuff from that time, and I think that was my engagement with music in a capacity where I felt like I was actually going somewhere.

When it came to production, in college, I got my first Mac product and immediately was on GarageBand doing that. And I was going to school for film, and I took a film scoring class that basically taught you Logic. “This is what compression does, this is what distortion does, this is what blah, blah, blah does.” And I had a base-level understanding. So from that point, I was making experimental… It pretty much always was industrial, either house or hip-hop music. So I remember there was one song where I peeled an orange and I just was trying to make…

Make that into the beat.

Right. And it wasn’t even from an avant-garde kind of place, it’s that I literally was just like, “What is a synth?”

So, it wasn’t like a daily, everyday thing, but I was keeping up with it. And when I first moved to New York, the music scene here was great. The comedy scene here is great. I can do both. And the first few months I was doing that. And then at a certain point, I was like, okay, I am too unemployed right now. One of these things is already an egregious assault to the pockets of any individual. Both of these things, I’m making negative money right now.

Then fast forward to 2020. I was really gearing up with standup at that time. So I was doing a lot of live shows and live event stuff. And when that was gone, I was like, okay, I have time to really buckle down and focus on making songs. I had for the longest time, been a writer and been writing things. And then I added on the experimental sound, like playing with sound and stuff. I was like, okay, what would it be like if I just genuinely tried to make some stuff? So at first, they were mostly jokes. I had one song that went platinum on my alt Twitter account that was about me being in a love triangle with Mitch McConnell and Madea.

A lot of your brethren in the comedy realm, your boy Hannibal (Buress, who raps under the nom de guerre Eshu Tune), your boy Zack (Fox, who recently released his single “Dummy”), they’re coming over on our side.

Jay Versace making beats.

What do you make of that? And why do you think the bars have stepped up so much? Because they’re all so good at it, I think is the thing that’s really stood out for me.

It’s funny, I was just thinking about this the other day, specifically thinking of Jay Versace, Zack Fox, Hannibal, people who are known to be funny, and then they go into music and it’s like, wait, okay, you’re kind of like… You’re hitting.

And even vice versa, in the other direction. I feel like it comes from the fact that even in the beginning stages of hip-hop, it wasn’t necessarily just music. There was just so much else built out around it. And it was an all-encompassing… Literally go way back, that one Hannibal joke where he is like, “Hip-hop. It started in the park.” That old school, that era, there was DJing, there was toasting, there was break dancing. There was rap. There were all these different components that were under the umbrella of the same culture. And I think that it never fully lost that, at least from how I’ve seen it.

There are Lil Wayne bars that are so funny. I look at someone like Vince Staples, he is a situational comedian on some of those songs.

He’s so funny.

Yeah, so funny. And the turns of phrase, the wordplay, there’s so many things that are foundational to standup, or to sitcoms, or to comedy in general. That I think there’s so much cross-pollination, it would just make sense at a certain point. I also think that the very stringent, “Oh, you do this one thing, you can’t do this other thing” — that just doesn’t feel like a Black thing to me.

I don’t know anybody that only does one thing.

Yeah. I didn’t grow up like that. Going to church, they were going to make you get up there and sing. They were going to make you get up there and dance.

You had to do the Christmas program. You had to learn sign language.

Exactly. I remember signing songs and shit. There was just a sense of art being something used to express an idea or yourself or this thing. Not necessarily it being something that is behind a closed door that only select chosen people can access. It’s more so these things are just an extension of what it means to be human. I feel like once you tap into that, it’s hard to listen to people being like, “You can’t do that. You only do this.”

Respect. So if there was one song out of the whole project that someone could listen to and get what you’re going for, which one is it going to be?

Impossible to answer. I think a part of why I made this project and sequenced it and why it came together the way that it did, was because of the fact that I felt like in everything else I was doing, I had to distill and boil down essentially myself into an easily understood, digestible, bite-sized little capsule. And with this project, it’s like I can’t pick exactly one thing. I would say though, if I had to tell someone to listen to one song, I would say “26.” Short and sweet.

Coming up on the close of the interview, I know you do a lot of interviews. I have to do a lot of interviews. You hear all the same questions, I have to ask all the same questions. What’s something that you’ve always wanted to talk about and you go into interviews, you’re like, I wish they would ask me about blank. And they never do.

I feel like it’s a question that I was kind of asking myself going into this project, or going into the release of this project and putting it together. Why? What was my reasoning for this project?

I think on a level, the answer is simply because I could. There’s definitely that. But then moreover, I think this project kind of felt like a record in the sense that it was really recording a period of time in my life and how I felt about music in general. The music that I listened to, where music was going, the internet, how the internet plays into music, how the internet has played into my life. How these technologies shape how we experience art, and whatever content it is that we’re consuming through the technology. And how that by extension affects our life. Even with the cover, there’s these memory sticks, that I’m holding this hand and there’s this hand holding me.

And with the sequencing and everything, I kind of wanted to replicate right now what the experience of listening to music for me at least, was like. It’s constant genre-changing, flipping through things, listening to a song for this amount of time, and then going and listening to the rest of a song. And that experience was really what I was trying to capture and replicate. I think the act of trying to honestly sum up what you’re feeling right now, what you’re seeing in the world right now, I respond to that in a work regardless of when it’s made. Seeing someone’s honest take on something is one of the most valuable things that you can offer up as someone creating something. And I like to think that’s what I was trying to do here.

So let’s say next year I’m walking around on Sunset, I bump into Jaboukie on Sunset, I say, “Jaboukie, what’s up man? How you doing?” And you’re like, “Aaron, what’s going on, bro? How you feel?” And then I say, “What have you been up to this last year?” What do you want to be able to tell me about the year intervening?

Whoa. I want to be able to say that SAG and WGA met all of their demands and more, and we vanquished the AI overlords who were coming to end our professions. And since then I’ve done a bunch of acting shit, toured, and have worked on some of my own shit.

Definitely when you come to LA, I will come see you, man. I will definitely come to see you.

Yeah, yeah, that might be pretty soon.

Tell them to let me know so I can go. And if you guys need me on the picket line, I will take some time off next week. [Editor’s Note: Aaron does not have permission to skip work to picket LOL]

All right. I will never forget. It’s not a lick, it’s luck.

It’s not a lick. It’s luck.

Yeah. I’m never going to forget that. So thank you. Thank you for sharing that moment with me.

All Who Can’t Hear Must Feel is out now via Interscope Records. Get it here.