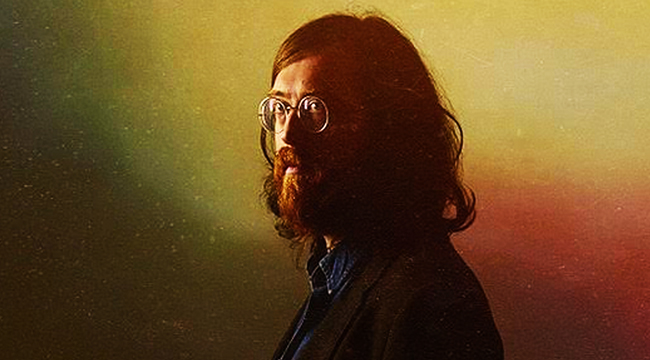

Speaking with Okkervil River‘s Will Sheff is to get the impression that he’s seen it all. Maybe it is just his band’s longevity — the formerly Austin-based project released their first music 20 years ago — and being an indie rock workhorse through a decade, the aughts, that was particularly kind to his musical stylings. Or maybe it’s because of the decade that immediately followed when the record industry shifted in a way that was particularly difficult for small and medium-sized independent artists. At this point, Sheff has charted and toured the world, he’s appeared on network TV and Coachella, and he’s had to endure a rebuild mode when the indie bubble popped and many of his bandmates needed to move on with their lives.

That last bit was the storyline surrounding Okkervil’s 2016 effort Away, but just two years later, Sheff is back with In The Rainbow Rain, an album that sounds big and bold and full of the sort of freedom that only comes from standing on the edge of a proverbial cliff. “I feel like I was in a doctor’s waiting room with fluorescent light, and was waiting for so long I didn’t know if the doctor would ever show up,” Sheff told me by phone from Atlanta between bites of barbeque. “So, I drew a door on the wall and walked through it and was transported to a rainforest that extended for miles and miles and miles.”

These last two albums of choosing his own destiny find a balance between keeping true to the integrity of the project and pursuing the sounds and ideas that interest him at the moment. There’s less trumpet than on Okkervil River’s early albums, but still plenty of the razor-sharp lyricism and the inviting melodies that have always been present. Even as Sheff becomes an elder statesman in the indie rock world, he’s also blessed with a creative peak that never seems to end. And, as he expresses repeatedly during our conversation, he’s basking in the fun of it all and not taking for granted the pleasure that comes with playing music with your friends. A line that he sang in 2005 now sounds truer than ever: “I’m doing what I really like, and getting paid for it.”

Below, check out a brand new Okkervil River video for the album standout “Love Somebody,” along with our discussion about the video’s subject matter of mental health and keeping things fresh after nine studio albums.

Usually when I talk to artists, it’s in advance of their album, and they are feeling anxious about the release. You’re now a few weeks after the release of your new album, In The Rainbow Rain. How does that feel?

It feels good! What I imagine most artists say to you, if they are being honest, is that time before an album release can psychologically be the lowest point that you feel in years. You finish this thing that you’re proud of, but by that point, you’ve usually lost all perspective. No matter how good you think it is, you don’t know if that comes across to anyone else. And even if you know that it is objectively good, that doesn’t matter because there is this narrative that is going to happen that you won’t be able to control.

That knowledge that things are going to happen outside your control is so terrifying because in this age of the music industry shrinking and withering, the stakes feel so high. It’s kind of an illusion, because in reality the odds are stacked so highly against any artist succeeding. And you have this illusion that if you do the perfect TV appearance or the perfect interview or the perfect video, then you are going to make a difference and tilt things in your favor. But what you are really doing is beating yourself up because you didn’t work harder.

The stakes might have to do with whether or not you’ll be able to make another album. So, I think most artists before an album comes out are a pile of nerves. Once the album comes out, though, you sort of realize that all of that was wildly exaggerated in the mind. Or maybe not exaggerated, since I think that everything I’m saying is somewhat accurate, but it’s sort of realizing that’s just life and we live in the real world and the real world is where the music came from in the first place and the real world is who the music is for. So, you return to the real world, and it’s a relief.

This is your ninth album, not counting stuff you’ve made with other people and EPs. Is it hard to keep the process feeling special when you’ve done it so many times? Or, the flipside to that is how does this time feel special to you?

There’s something that people have said to me during this cycle that I’ve never heard before, and that thing is ‘I’m so glad that you mix it up with each album,’ instead of doing the same thing and repeating a formula. It’s a funny thing to hear because I’d never intellectualized that was a thing that maybe you shouldn’t do. Being a classic rock fan, I always had The Beatles and David Bowie in my life, so there was a feeling that you should make things sound different.

But that sense is also organically rooted, because often with an album, I’m trying to scratch an itch or exercise some demons. Maybe there’s something that is really bothering me and I want to explore it. And the process of writing about it and performing the songs, I want to become less bothered and feel more at home in the world. Or, maybe there is a part of music that I love that I’ve never articulated before, and I want to get the chance to do that.

So you do that, and you go out and play those songs hundreds of times, and you wind up facing in the opposite direction because at that point you are sick of what you did before. For me, I’ve never felt like making music is routine and I’ve never felt like I have to fight to keep it fresh. But that’s not to say that it won’t happen, and if it does, that would be the time to stop. I’m lucky enough that I’ve always felt like I had some demon to exercise or some good time that I wanted to have. It doesn’t feel like going out every night to the same restaurant. It feels like you are going to a new restaurant in a different solar system to me.

It’s important to stay connected to some sense of childlike wonder and passion, and as you get older, that gets to be more of a challenge. Part of that might be that your brain literally loses some of its flexibility, but it also is inevitably true that the world at large, well, the lanes narrow and you get shunted into a less inspired existence. At that point, you have to get to this next level where you are cracking into the real deep sh*t that was lurking behind your earlier work but you didn’t have the tools to unlock yet.

Your new video speaks directly to some of that “deep sh*t” in that it tackles mental health. Can you speak to your relationship with mental health?

I think that what I’m about to say is a pretty common story among creative types. I was naturally talented at putting together words and playing make believe. But lots of people are like that. The thing that made me want to do that not just as a career but as a vocation was damage. That’s what pushed it from being a fun hobby that was a balanced part of an integrated personality into an obsession. And that’s what allowed me to be successful I think, was that it was an obsession and it wasn’t healthy.

I think that is a common trait among people who become professional artists, especially ones that have some level of success, is that they get it with the worst parts of themselves. And by worst, I mean most weak and vulnerable and desperate and hungry and broken. I was also lucky in that I had wonderful people around me with family and friends who set really good examples and made me realize that being a good person was more important than being a good artist.

Somewhere along the line, I got it into my head, be it through my grandfather or the artists I admired, that it is the job of the artist to make pretty things and your life should be a work of art, too. I don’t mean that your life should be flamboyantly colorful, though that’s great. I think that you should be there for people and make them happy. The more that I wanted to connect my art to the deep groundwater, the more I tried to understand what was holding me back from being more helpful to people. And, drugs and not wanting to be a drug addict. And not wanting to be a tyrant, because I’m an artist that has a very specific idea of what he wants and can become tyrannical. It’s something that has alienated people. I wanted to be able to bring comfort to people as a human being, and not just as an artist.

I started going to therapy when I was ten or eleven years old because of an episode I had that scared my parents. That’s when I started meditating, too. I stopped when I was 15 and started going again on and off for a long time. That’s what “Love Somebody” is about to an extent, this idea of going to see people to help you. It’s also what led me to entheogenic drugs like psilocybin, it led me back into meditation, and to Quaker meetings and getting more into spirituality. It’s about trying to do the best work I possibly can and doing it without doing the Rimbaud thing. He talks about a derangement of the senses, so I was trying to derange my senses while still remaining a person who sees people around him and tries to be kind and compassionate to them.

I’m lucky because I haven’t had struggles with depression in the way that some of my best friends have, or being bipolar or things like that. For me, it has always come out of trying to spread beauty, and I think that comes through on “Love Somebody.” I started out with the idea of how much you are supposed to give up for somebody else, because you aren’t really being that helpful if you are a martyr to other people. But then I wrote this long bridge that is pretty much stream-of-consciousness trying to figure out my relationship to the people that I love and with the audience that I perform for and with America to a certain extent. Maybe I’m making it sound grander than it is, because really I’m just barfing out a bunch of anxieties. But what I’m saying is how can I help the world when I can’t help one person? That’s a question that I have a really hard time with.

You said there that your story isn’t necessarily original to you and could apply to a lot of musicians. It feels like this topic is coming up a lot lately, recently with the death of Scott Hutchison of Frightened Rabbit, and seeing people in the Los Angeles music scene talking about creating a fund or resource to help get musicians without health insurance the mental health services they need.

There are some organizations that do that. There is MusiCares, which is awesome. And in Austin, there is the SIMS Foundation. Austin is great that way because they have so many working musicians. But there should be more organizations and funds like that.

It was something that came to mind when watching the video, this recurring situation of people needing help and feeling like the music community in some way let them down.

I hesitate to say what I’m about to say because I don’t want it to seem like I’m claiming someone else’s thing. I didn’t know Scott though I was familiar with Frightened Rabbit. I know a lot of people who knew him, and that was my entry into their grief to some extent. My conversations around his passing with other musicians, and what is really so sad, is how familiar this all is. Which isn’t meant to diminish the singular example of his death.

But yeah, this is something that a lot of musicians do struggle with and a lot of musicians don’t have health insurance. I don’t have health insurance. And that intersects with their art in ways that are quite complicated, because that depth of pain can create great work. Sometimes that’s a cliche, but what I think is that when you are in pain, you don’t have much desire to bullsh*t people or the bandwidth to bullsh*t people when you are in pain. So, your work has this badge of honesty that people need to hear. But, that can hurt you. And the desire to be successful in music can come from some pretty dangerous parts of your psyche. For me, that’s definitely the case.

But what’s interesting is the parts of my psyche that were responsible for my success and were dangerous and hurt me and hurt other people — they did make me think that way. That’s a really odd aspect of it. The fact that the music industry is such an unforgiving world and you’re putting your soul on the auction block for someone to give a thumbs up or thumbs down to, that adds a layer, too.

The other side to that is music’s power to be therapeutic to the listener. In The Rainbow Rain feels that way, in that it’s warm and comforting and generous, similar to one of your earlier works, The Silver Gymnasium. And you’ve spoken about the desire to put something pretty or positive into the world, but that does seem at odds with the way many artists create, where it is very insular and without much regards for how it is received.

That’s a very complicated thing, because you have to write for yourself. But if you just are writing for yourself… it’s a mysterious relationship that I feel like I have a hard time articulating very well. I don’t even feel like I understand it. But there was a recent Bruce Springsteen quote that resonated in me where he said something like “I’m like a guy who i fixing up my house, and if I figure out how to fix something in my house, maybe you’ll figure it out by seeing me do it.”

To some extent, I’m writing In The Rainbow Rain to comfort myself, but the idea is that if I can comfort myself, hopefully it is comforting to other people. If you write with a goal of just writing for other people, then you remove yourself from your own experience and it’s not going to connect with them. But if you disappear up your own ass, that’s not helpful either. There has to some level of knowing what people might feel.

On this album, I wanted to run the risk of writing something corny. I like the idea of giving people sounds that were pretty and fun and made them smile, and then saying things to them that were simple, like ‘I’ve got no idea what you’ve been through or had to do or rose above’ or ‘I thought that I was all alone.’ You can sing those words to people and wrap them up in velvet, and give them this warm and fuzzy feeling. And if people want to kick me down for that, then that’s okay, too.

In The Rainbow Rain is out now on ATO Records. Buy it here.