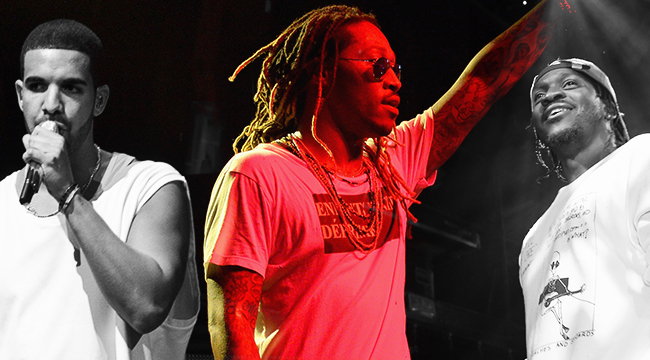

In a post for Future and Zaytoven’s magnificent Beast Mode 2, it became clear that after the exhausting 25-song adventure that is Drake’s Scorpion and the short and sweet morsel that is Pusha T’s Daytona, Beast Mode 2 was like a refreshing happy medium with regards to its succinct yet fulfilling length.

However, almost as soon as the words had left my keyboard and the post had gone live, I found myself questioning that sentiment. I’d called it the “perfect length” for a rap album, but my naturally skeptical inner voice almost immediately chimed in with questions, interrogating the very concept. What is the perfect length for an album? What are the criteria? And why, oh why, are we rap fans so damn obsessed with this idea of perfect album length in the first place?

The album length discussion always crops up from time to time, but particularly around Drake’s decision to make Scorpion 25 songs almost immediately after Kanye West’s GOOD Music had gone on a mini-album rampage of five 7-song “albums” in the span of the same number of weeks. That deluge of new music followed a seemingly industry-wide trend of supersizing albums to exploit streaming figures that included Migos’ Culture II, Drake’s two previous projects, Views and More Life, and even Future’s own double album from 2017, Future/HNDRXX.

All of this discussion resulted in any number of music fans asking the album-length question in a struggle to define just what differentiates an EP, an LP, a double album, or mixtape, with everyone weighing in with opinions about the perfect length for an album. The debate even stretches to considering the “future” of album length, as if these trends are indicators of an overall revolution for projects yet to come.

So, let’s put the debate to rest: There is obviously no such thing as an ideal album length. Albums should be as long as they need to be to accomplish whatever specific goal they set out to achieve, whether that’s to fudge the streaming numbers to inflate the perceived interest in the artist and generate revenue or tell a concise, complete narrative in a specific amount of time.

As for what defines an EP or an LP, the answer is simple: Whatever the artist deigns is appropriate for their individual purposes. It’s how Kendrick Lamar could get away with releasing the 15-track Kendrick Lamar EP in 2009, following that up most recently with DAMN, an album that was ostensibly shorter with only 14 tracks and a runtime of 55 minutes. Between those two releases were the blank Memorex CD-filling To Pimp A Butterfly (79 minutes), the 12-track Good Kid, MAAD City which somehow comprised a runtime 13 minutes longer than DAMN.‘s, and Untitled Unmastered, a “compilation album” composed of eight Butterfly throwaways that plays through its 34 minute runtime more cohesively than the majority of rap albums released the same year.

Obviously, the elements that originally restricted albums to these original categories have become obsolete — hell, even the term “albums,” which originally grew out of the name for the twelve-inch vinyl records on which the music was pressed when there were no other alternatives, seems quaint in the era of instant streaming collections and user and brand-curated playlists that have largely eliminated the need to own physical media in order to listen to a given song. In fact, with the on-demand nature of services like Spotify, Apple Music, Tidal, Soundcloud, Pandora, and Youtube, many listeners are more comfortable simply picking and choosing individual favorites to play or trusting in computer algorithms to help them discover new tunes similar to their existing taste than simply purchasing an album and letting it play from end to end.

Even big box retailers have seen the writing on the wall; Best Buy, one of the last purveyors of compact discs in the streaming era, has stopped selling CDs, while Target still sells the rapidly-dying media, but only under consignment basis, only paying for CDs that their customers purchase. Those customers are buying fewer and fewer physical discs by the day; after all, why restrict your music listening to a cost-ineffective source that can only contain so many minutes of content when $12 a month gains access to all the music anyone could possibly want (with a few exceptions — shout out to Jay-Z’s back catalog’s Tidal exclusivity)?

Albums aren’t like movies, where you have to sit still and absorb the full 90 minutes, two hours, or franchise sequels to understand the narrative. They are more like books; you can start and stop at your leisure, finding spots that lend themselves naturally to your own pace and the purposes of the story that is being conveyed. In Pusha’s case, Daytona felt like a novella; it ends just as you want to see where the story is going, so it doesn’t feel like a complete statement. It’s more like being cut off midsentence. Meanwhile, Drake’s album is like a gigantic, dusty old tome or a research text. It’s almost too dense to really absorb anything more than a few pages at a time. Maybe that’s by design; after all, few rappers have mastered the language of the modern zeitgeist like The Boy. Already, fans are cherry-picking their favorite songs to turn into their own summer anthems and viral dance crazes. By giving them so many options to choose from, Drake ensures that everyone will find at least one thing they like and keep it in rotation. Meanwhile, Pusha wants you to consume his whole album in a go, but that doesn’t always lend itself every situation. You may not have time for a complete play-through, but cutting off an already short statement makes it feel even more choppy, almost incomplete.

By contrast, Future and Zaytoven found a perfect balance between making their album sound finished, yet digestible. Listeners can pull out their favorites, and have already begun to do so, but they can also throw on the album during a morning commute and finish just as they reach the office. This is probably what consumers truly mean when referring to “perfect” album length. It isn’t always about a specific length, but about the balance. We want to be able to listen to projects as complete narratives and we want to be able to pull out specific tracks for placement on playlists or to throw on repeat without feeling like we’re missing some larger point that the album wants to make. The future, it turns out, isn’t really about shorter albums or longer albums. As it always has been, the future and present of music is about balancing quality with quantity, making music so good that fans leave satisfied but looking forward to more.