Ever since it was announced in January, Vampire Weekend’s fourth album Father Of The Bride has been the most anticipated indie rock release of 2019. This is due to the band’s pedigree, which includes three classic records released in the late ’00s and early ’10s that are considered millennial touchstones. And then there’s the exceptionally long six-year gap since the most recent Vampire Weekend release, 2013’s Modern Vampires Of The City. In a way, Vampire Weekend at this point is both a legacy act… and a completely new band.

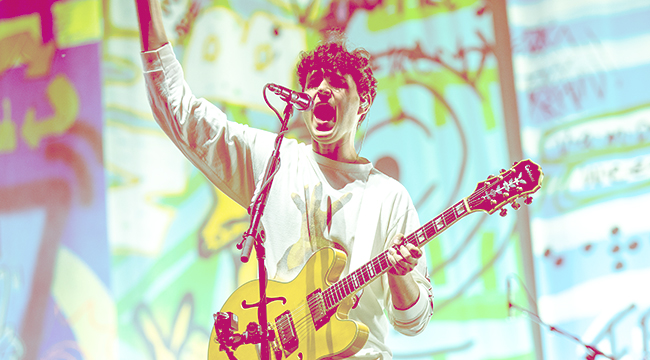

The early singles from Father Of The Bride certainly sound like classic Vampire Weekend — all clean guitar lines and gently syncopated rhythms and a polymorphous production aesthetic that freely draws on contemporary R&B, hip-hop, and even jam-band rock in a way that feels unforced and generous. Lyrically, Ezra Koenig is many miles down the road from Modern Vampires, his late-20s “mortality” record, though he hasn’t abandoned the over-educated and emotionally confused upper-middle-class characters of previous Vampire Weekend records.

“The people in “Oxford Comma” and “White Sky” and “Step”—I had this feeling this is where those people are now,” Koenig recently told GQ. In the philosophical “Harmony Hall,” this connection is made explicit by Koenig evoking a pivotal lyric — “I don’t wanna live like this, but I don’t wanna die” — from the Modern Vampires track “Finger Back.” You can also detect this strain of existential anxiety in the deceptively bouncy “This Life,” in which the quarter-life crisis of a self-involved and unattached 20something mutates into the gnawing fear of the young family man who suddenly has a lot more to lose. (“Baby, I know hate is always waiting at the gate / I just thought we locked the gate when we left in the morning.”)

But while there are discernible sonic and thematic connections between Vampire Weekend’s old work and the new songs, seemingly everything else has changed. Rostam Batmanglij — the band’s keyboardist and producer, and Koenig’s primary songwriting partner — announced his departure in 2016, though he’s remained in Vampire Weekend’s orbit as a contributor to Father Of The Bride. While Koenig has always been the band’s focal point, Batmanglij’s role in creating the layered, pan-cultural sound of Vampire Weekend’s previous records can’t be overstated. The arc of Vampire Weekend’s first three albums — from the engagingly bright Graceland-isms of the self-titled record, to the piecemeal laptop-pop of Contra, up through the introspective pocket symphonies of Modern Vampires — is as much about Batmanglij’s evolution as a producer as Koenig’s maturation as a writer.

Along with the changes within Vampire Weekend are the myriad cultural shifts that have occurred outside the band. The context for Vampire Weekend is entirely different in 2019 than it was in 2008. For a younger listener who didn’t experience those first three records in real time — Koenig has described them as a trilogy, and in retrospect, they truly do feel like a self-contained piece about life from post-college to the onset of 30 — might be shocked to learn how controversial Vampire Weekend once was. Nothing seems controversial about those effervescent, charming, and exceedingly well-crafted albums now, but back then, Vampire Weekend was among the most divisive indie bands of the era.

I say that as someone who, yes, at one point was bothered by Vampire Weekend. At the time, they were frequently slagged as privileged tourists ransacking African music styles for the sake of songs about rich people navigating rarefied social strata. Familiar charges of cultural appropriation were made against Vampire Weekend, though what seemed to really rankle the band’s detractors was their preppy, fashion-conscious, and decidedly un-rock and roll approach to being an indie-rock band.

This was the era of indie’s greatest ubiquity, a period of iPod commercials and Zach Braff movies and widespread angst about the pernicious influence of “hipsters.” For those who couldn’t stand what was happening in left-of-center music, the tweedy fellas in Vampire Weekend swiftly were rendered as shorthand for a movement. As one of the harshest critiques of Vampire Weekend from that time concluded, rather reductively, “indie rockers are supposed to be grubby proles, not graduates of Columbia University.”

Keep in mind that Vampire Weekend emerged seven years after the Strokes, who also had connections to wealth and privilege but had the decency to conceal it by donning leather jackets and their own discarded cigarette ashes. As the next link in the chain of “important” New York bands, Vampire Weekend represented a decisive break from that sort of acceptably grimy and street-friendly iconography. Ezra Koenig was obsessed with writing about the nature of status and the dubious value of status symbols in his songs; as the leader of Vampire Weekend, he also deconstructed the aesthetic clichés of rock bands. In the process, he eschewed a lot of what preceded him during the early ’00s “return of rock!” era: guitar distortion, decadent posturing, machismo, and the narrow canon of “acceptable” late ’70s punk and post-punk. Vampire Weekend, unapologetically, was a pop band, with none of the hangups about music outside of that “acceptable” NYC rock zone. He was a musician first, but Koenig (with heavy assistance from Batmanglij) operated as something like a music critic, though he chose to make records that satisfied his tastes rather than pointing out the deficiencies in music by others.

Naturally, this meant that Koenig was attuned to what critics were saying about his music, and uniquely equipped to rebut it. As he put it, more or less correctly, to The Guardianin 2013, “Referencing other cultures and making music that combines those things, it’s complicated. People with money, education, these things are complicated. But rather than admitting that we understood that, too, people tried to pretend that we were rich idiots ripping off African music.”

For the record, I finally came around on Vampire Weekend via Modern Vampires — their most writerly record, the one that’s thick with somber story songs like the stunning “Hannah Hunt” that, unlike the first two albums, stubbornly avoid the dance floor. Of course that would be the one that a holdout music critic would like, though over the years I’ve found myself gravitating more toward the first two albums, particularly the infectious debut, with its surfeit of perfect singles that skillfully manage Koenig’s youthful snark with his burgeoning empathy.

Modern Vampires does seem like Vampire Weekend’s most crucial record, however. By 2013, Vampire Weekend was the most respected brand in indie. (Modern Vampires finished right behind Kanye West’s Yeezus at the top of the Village Voice‘s annual Pazz & Jop poll.) There was also a new generation of indie acts that had followed Vampire Weekend’s example, taking what had once been considered transgressions against indie orthodoxy for granted as the current matter of course. Some of these acts, such as Haim and Sky Ferreira, worked with the producer Ariel Rechtshaid, who also co-produced Modern Vampires. And then there was The 1975, who in time would come to take Vampire Weekend’s position as the reigning pop-friendly indie act (or is it indie-leaning pop act?) that most annoyed the old-school purists.

What is Vampire Weekend if it no longer signifies the polarizing indie vanguard, or really anything about youth culture? The early singles from Father Of The Bride have a decidedly easygoing, dad-rock sound — while that has always existed in this band’s music, Koenig seems to be negotiating impending middle age with the same ease and honesty as he once addressed the identity crises of young upwardly mobile urbanites. In that interview with GQ, Koenig made a pre-emptive strike against expectations that he might once again command the zeitgeist. “On the last record, I had this slight feeling that we got a little bit too big,” he asserted, adding that he would be fine if Father Of The Bride made Vampire Weekend a little less big.

While I haven’t heard yet the bulk of Father Of The Bride, I’ve come to view Koenig more and more as a Paul Simon figure for a new generation — not just because of those easy Graceland signifiers, but also Koenig’s relaxed yet insightful way of describing how life changes your circumstances but not your essential self. The circumstances of Vampire Weekend’s moment ensure that the band’s early trilogy will remain sequestered from whatever the band does next. But the immutable spirit at the band’s core continues to be a witty and welcoming portal to a changing world.

Father Of The Bride is out 5/3 via Columbia Records. Get it here.