With the possible exceptions of The Beatles and Bob Dylan, no artist has been as analyzed or anthologized as much as Elvis Presley. You could open a library stocked solely with books dedicated to re-telling his story. The definitive take on Elvis’ life, Peter Guralnick’s exhaustive companion books Last Train To Memphis and Careless Love, totals more than 1,300 pages. Add to that numerous reissues, greatest hits albums, and boxed sets, as well as the mythology that American culture imprints into the minds of everyone who cares about popular music. Even if you think you don’t know Elvis’ music, you probably know the basic facts of his life: He was born poor, he became famous for being a handsome white guy who sang black music, he got rich, he died fat and miserable. Cue the lip curl and a half-assed “thank you, a-thank you very much.”

In spite of all this, Thom Zimny’s new documentary Elvis Presley: The Searcher, which premieres Saturday on HBO, justifies its existence. For starters, there’s never been a truly great doc made about Presley; before now, you had better luck finding a quickie, low-budget, straight-to-video expose about Elvis’ current whereabouts in Canada than a serious and handsomely produced examination of the man’s life and career.

Like Guralnick, Zimny digs in deep — over the course of two parts and more than three hours, The Searcher charts Elvis’ rise from poverty in small-town Southern America to his tragic fall from international stardom using a wealth of intimate, previously unseen footage from Graceland’s vaults. In the process, The Searcher successfully re-approaches the Elvis saga from a uniquely human angle, though the mythology ultimately proves too towering to completely overcome.

If The Searcher feels surprisingly urgent, it might have something to do with the mortality of Presley’s supporting cast. Many of the confidants who talk about Elvis in The Searcher — each interviewee is kept off-screen, so that their remembrances can play off of the vibrant and melancholy images of Elvis from throughout his life — are no longer with us. A good number of these people have died just in the past few years, including his original guitarist Scotty Moore and close friend Red West.

And then there are the lifelong diehards who vividly recall the seismic impact that Presley had on American culture in the mid-’50s, like Tom Petty, who is among the warmest and most soulful speakers on how transformative Elvis was for a generation of bored, stifled kids who grew up to be rock and roll devotees.

While the power of Presley’s greatest records has not diminished, the number of people who witnessed him in his prime firsthand is dwindling. It’s not an exaggeration to suggest that a film like The Searcher probably couldn’t be made a decade, or even five years, from now. In terms of documentaries, The Searcher might very well end up being the final word.

You call tell that Zimny is trying to set the record straight. While Elvis is still famous enough to go by just one name, his stature has undeniably been diminished since the dawn of the current century. The more problematic aspects of how he is discussed and contextualized have superseded his artistic primacy. In 2018, Presley’s tenuous connection to modern life is as a symbol of how the importance of white artists historically has been over-emphasized at the expense of their black and brown counterparts. “Elvis” has been rendered as shorthand for cultural appropriation, a cudgel that’s wielded to slam anyone — whether it’s Eminem, Justin Timberlake, or Macklemore — accused of “stealing” black music.

As an Elvis fan who has occasionally been put in the position of defending him, I tend to push back against the “King of Rock and Roll” mythos and refocus the conversation on Elvis’ talents as a masterful singer and synthesist of nearly every style of American music. If you can appreciate Elvis as an artist who combined what he loved in new and exciting ways — as opposed to the guy who “invented” rock and roll all by himself — it’s easier to view him as part of an ensemble that includes so many ’50s greats, both black and white.

Elvis is not the sole protagonist of rock’s origin story. But properly contextualizing him with his peers also shouldn’t minimize his talent or significance. Elvis could not write songs like Chuck Berry, he wasn’t as transgressive as Little Richard, he wasn’t as wild as Jerry Lee Lewis, and he didn’t inform the modern rock singer-songwriter archetype as profoundly as Buddy Holly. But Elvis Presley unquestionably is a pivotal figure in 20th century popular music history because of the depth and width of his artistic vision — which encompassed blues, rockabilly, country, light opera, R&B, gospel, folk, and saccharine pop, among many other genres — and his ability as one of the most famous men who ever lived to bring the audiences for those genres together, often for the first time.

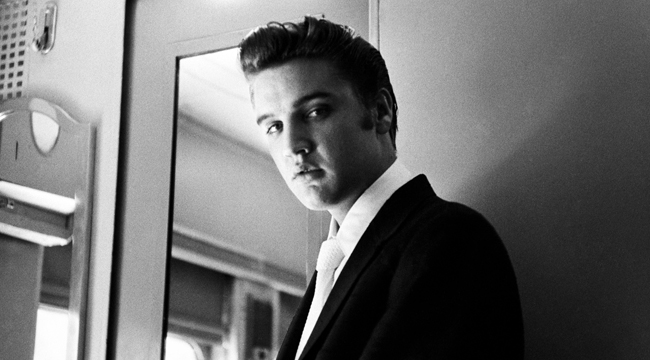

In The Searcher, Zimny attempts a similar rhetorical maneuver, portraying Elvis less as a god than as a seeker constantly looking for new forms of enlightenment, whether it’s via music, fame, religion, or drugs. Zimny’s best tools are the photos and video clips of Presley as a gawky, unformed young man who was told from an early age that he had to live a big enough life to also accommodate his deceased twin brother Jesse, who perished in childbirth. The Searcher attempts to show the Elvis that existed before the Elvis we all know was invented — as much by the media and his hucksterish manager, Col. Tom Parker, as Presley himself

Zimny’s thesis — formulated with the film’s writer, veteran critic Alan Light — is that Presley was motivated by a combination of boundless lower-class ambition, an intense devotion to his mother Gladys, and a kind of insatiable spiritual restlessness. He was not an oracle; he was a misfit who unknowingly signified everything that millions of people didn’t know they wanted, and appeared at the moment when modern media, a burgeoning teen economy, and the civil rights movement aligned. He was a man of destiny, and an act of historical serendipity.

The Searcher posits that the central tension of Presley’s life was his struggle to preserve his own humanity against the constant grind of Elvis Inc. This struggle continues in Elvis’ afterlife, and also weighs on The Searcher. For all the film’s gestures toward Presley the man, it can’t help but genuflect in the direction of Elvis the deity.

Many of the interviewees fall back on cliches about how Presley “changed the culture” by alerting white folks to the ecstasy and catharsis of black music. While no ill will is intended, this framing of music history — as a series of events in which white people discover the “earthy” and “liberating” culture of “others,” without a balancing perspective from those outside of white culture — is precisely why so many contemporary listeners have problems with Elvis Presley. The reductive view of black music as a purifying agent for open-minded whites that’s endemic to Elvis mythology has provoked equally reductive reactions from critics about Presley’s supposed racism, which is refuted by any honest accounting of Elvis’ respectful engagement with black artists during his lifetime. The racial element of Elvis’ story is undoubtedly complicated, and could warrant its own stand-alone film. But the decision to essentially bow out of the conversation in The Searcher feels like a lost opportunity.

While the thornier aspects of Presley’s legacy remain unresolved, The Searcher provides an equally essential service by exposing new generations to his music. The movie dispels the commonly held belief that Presley peaked early with his Sun Records era and the beginning of his RCA years. Presley actually put out quality music during nearly every part of his career, which The Searcher ably covers by spotlighting some of his lesser-heralded periods — like his post-Army/pre-Hollywood records from the early ’60s, or his pained post-divorce ballads of the early ’70s, or the gospel music he released throughout his life.

Perhaps the story we think we all know about Elvis Presley is slightly wrong. He wasn’t just a pretty kid who peaked early and burned out over the course of two decades. In The Searcher, he roams far and wide, and he does not go gently.