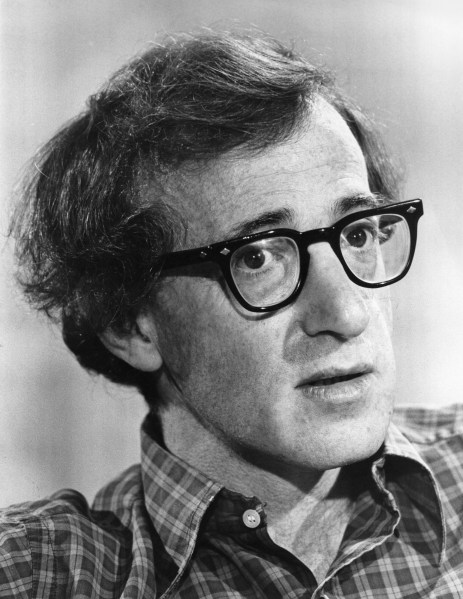

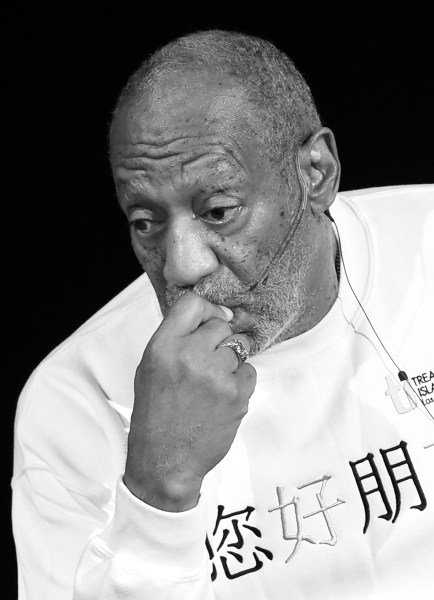

Earlier this week, Ronan Farrow wrote an essay in The Hollywood Reporter challenging the media to talk about the charges of sexual abuse that his sister, Dylan, has leveled against their father, Woody Allen. Farrow pointed out uneven handling of the story and the fact that Allen is rarely asked about the charges (charges that Allen has made it clear he won’t talk about). The reemergence of this case in the public eye — along with the Cosby accusations, and the long-simmering story of Roman Polanski’s sexual assault — brings up questions about how we relate to the people who make art in our society. The problem itself isn’t new, but it does deserve to be reevaluated as sensibilities shift and evolve.

The questions Farrow poses are important and deserve a place in our cultural conversation. So we asked three writers — Steve Bramucci, Vince Mancini, and Jenni Miller — to discuss the issue — not in hopes of finding a solution, but simply because thinking about these issues is a better alternative than staying blind to them.

Steve

I read about all of those Hollywood power players asking for leniency for Roman Polanski on Filmdrunk, and I remember it registering highly on my “this is f*cked up” meter. Because the guy drugged a 13-year-old and had forcible sex. He also had multiple accusers. So why is Whoopi Goldberg going to bat for him? How does he get Martin Scorsese in his corner after that? Is it because of all the time that’s passed? Is it some vague notion of a “different era”? Or is it connected to his immense creative talent?

Of the questions posed above, the one that seems scariest to me is the last one. Because it’s weird to think that talent makes us more forgiving of people when it comes to sexual assault. Artistic brilliance doesn’t magically balance out horrible behavior. They don’t operate on the same plane; there’s no causality between the two. I mean, the idea that artists and visionaries should be forgiven for eccentricity is timeworn, but how far does that extend? The Cosby Show was something I adored as a kid, but it hasn’t been in my purview as an adult, so I haven’t been forced to confront the issue, not really. But I think Ronan Farrow’s essay brings up interesting points about Woody Allen. He’s basically saying, “Please don’t work with this man, please don’t watch his movies.” If we’re willing to assume that Farrow’s allegations are true, I tend to agree with that line of thought.

We all have to draw lines in the sand. For me, if a person is generally bad (cursing, berating others, destroying hotel rooms), I can still enjoy their artistic output. I might not want to hang out with them, but I can enjoy their work. But when someone goes full-sinister (sexual assault, child abuse, murder), I don’t want to support the stuff they make. Besides, the information I have makes the work less enjoyable. Vicky Cristina Barcelona just doesn’t play like fun, pansexual romp anymore when I’ve got the entire Farrow/Allen backstory in my head.

Vince

It’s tough. Enjoying the work of an artist who has done terrible things is a lot more complicated for me than, say, watching a white supremacist fight MMA or domestic abusers play football. I’ve always thought it was silly when people interpret wanting to see a person get punched in the face or tackled as some kind of tacit endorsement of their personal lives. How can I enjoy the gladiator match if one of them is a bad person!? It smacks of meaningless PR that doesn’t actually accomplish anything.

That said, art isn’t sports, and I do think our enjoyment of it is a lot more closely wrapped up in the personality of the artist. The root of it comes down to the question: Are we allowed to enjoy something a rapist/molester/murderer does when he’s not raping/molesting/murdering? And, I would argue, the answer to that depends on another question: Is the art — or, more broadly, work — an attempt to profit off of the criminal acts or an attempt to atone for them?

Put it this way: I’d feel gross buying O.J. Simpson’s tell-all book about the murders. I wouldn’t feel gross working on an O.J. Simpson project building houses for poor people (should that ever become an option). Very few people are all bad or all good, no matter how much we want to pretend it’s that way. If they’re trying to do good, let them. How many good works come out of guilt, or megalomania? At a certain point, questioning motives is self-defeating.

Of course, there’s a broad swath of grey area between exploitation and atonement, and most of Woody Allen’s work seems to fall somewhere in between. I do think it’s pretty weird that guy accused of molesting one ex-wife’s kid and marrying another makes so much art about older men dating younger women. It was 41-year-old Joaquin Phoenix and 27-year-old Emma Stone (who was playing a college student) in Irrational Man (my review) and 55-year-old Colin Firth and Emma Stone in Magic in the Moonlight (my review), just to name the last two.

(Some commenters always try to claim that because those kinds of relationships happen in real life that it’s unfair to criticize Woody Allen for depicting them in his art. First of all, give me a break. Secondly, it’d be different if it was just one film and not a pattern, to the point of it being a tic. Imagine you‘d been publicly accused of molesting your ex-wife’s daughter and were currently married to another. Would you have the balls to continue depicting those relationships in your movies? I’m pretty forgiving, but that seems incredibly tone-deaf, and not being tone deaf is central to an artist’s job.)

The most damning part of Ronan Farrow’s essay is the part about media coverage:

When The New York Times ultimately ran my sister’s story in 2014, it gave her 936 words online, embedded in an article with careful caveats. Nicholas Kristof, the Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter and advocate for victims of sexual abuse, put it on his blog.

Soon afterward, the Times gave her alleged attacker twice the space — and prime position in the print edition, with no caveats or surrounding context. It was a stark reminder of how differently our press treats vulnerable accusers and powerful men who stand accused. [THR]

Woody Allen obviously has a lot more power to influence the narrative, and it’s important to give at the very least, equal space to the accuser. The point is to encourage current and future victims to speak up.

But even if I believe that Woody Allen is 50 times more likely to be the one lying in this situation (and I do), I still don’t feel entirely comfortable burying the guy, when he hasn’t been convicted of anything. I wasn’t there. And I think (hope?) you can say that without shaming the accuser. I would hope we can still empower victims to come forward while acknowledging the possibility, however minuscule, of false or mistaken allegations. It’s not either/or.

What about Cosby, then, you might say? He hasn’t been convicted of anything either. Well, that’s a little different. Cosby has what, 60 accusers now? I feel pretty comfortable in assuming he’s guilty at this point. The Cosby situation is a much clearer failure of the law. The law not punishing Cosby has forced the court of public opinion to step in. The public shaming was essentially a last resort, and it took way too long. That’s the thing — we aren’t supposed to need this kind of press trial, that’s supposed to be the court’s job.

Woody Allen doesn’t have 60 accusers, so it’s a little less clear. Should public opinion step in because he’s probably guilty? Or do we leave him alone based on reasonable doubt? I’m not entirely comfortable with either. I guess where I come down is that I can enjoy his work if it doesn’t remind me of the allegations and feel creepy. And his last couple movies… yep, they felt kind of creepy.

My question is: Mike Tyson has actually been convicted of rape, and he seems like the entertainment industry’s darling. Is it hypocritical that we throw roses at convicted rapist Mike Tyson’s feet after his one-man show and let him sell us video games while we have this argument about non-convicted rapist Woody Allen? Or do we not have to argue about Mike Tyson anymore because the law had its say?

Jenni

This all feels very personal to me, in that our experience of art is inextricably linked with the person who created it, as well as who we are and the various things we bring to the table when we engage with that art. I’ve definitely thought and said to friends things along the lines of, “Well, we don’t really know what happened…” But f*ck that. I believe Dylan Farrow. I’ve enjoyed Woody Allen movies, and even given one or two fairly positive reviews, and trying to reconcile this makes me feel sick. At the same time, I don’t have a deep emotional connection to Allen’s films as a formative experience, other than watching Annie Hall while stoned with a particularly nebbish boyfriend, so I’m sort of relieved there’s one less so-called auteur I can stop pretending to give a sh*t about, professionally speaking. The luxury of being a freelancer is that I don’t have to engage with Woody Allen’s movies unless I feel like it, or unless the money is really good, and generally I don’t and it isn’t.

That queasiness that rumbles in your tummy every time you think about how much Manhattan once meant to you and now it’s forever tainted etc. etc.? That’s more about the knowledge that not only can an artist be a monster to his loved ones, but that anyone can be. You can’t tell by looking at someone what kind of havoc they’ve wreaked on the people around them; maybe you can suss it out by watching their films or reading their books or parsing their letters to their wives, but the truth is that a predator looks like just another schmuck on the street.

Everyday evil is mundane. It can be charming, it can be witty, it can win Oscars. It has its defenders, and those defenders are people you used to respect and endeavor to dress like, with those kicky little pantsuits and floppy hats and whatnot. But the really sickening thing is that Woody Allen is no different than any other child molester; he just happens to make what some people think are great movies.

The question isn’t whether or not we should enjoy his movies, but the fear of what it means that we might enjoy them anyway.

Steve

I want to hop back to that atonement point Vince made for just a second. Stan “Tookie” Williams (who started the Crips and was both directly and indirectly responsible for multiple murders) wrote children’s books on Death Row. He was coming from a place of contrition and trying to share wisdom, and I’m glad he did. He was also being punished in a more conventional way, too, so it’s pretty easy to say, “Yeah, this has positive net value, he’s involved in the process of penitence.”

With Tyson, it’s trickier for me. Sure, he served time (significantly less than the national average for the crime he was convicted of), but does that mean he’s clear now? Is it all good to laugh when he’s in The Hangover? Does that mean rape is a mistake that people make and can atone for and then have it be, essentially, over? Is that what society has collectively decided?

I think Farrow is right to be concerned about the media and, as a member of the media, I would say this: It’s a scary topic to cover. Even this discussion requires delicacy and will be vetted by far more people than the average article. Not because we might lose access to famous people, but because there are endless layers and shades of gray. Speaking for myself, I don’t want to be the guy who covers it and f*cks it up by “mansplaining” or victim blaming or failing to recognize some angle. I actually had a piece I was writing about Kobe Bryant the week he retired, and I went down the rabbit hole of reading both his police interview and the trial transcripts, and… I completely lost the thread of the story I’d set out to tell. I had to kill the piece. I just couldn’t gloss over the rape case and yet I couldn’t discuss it with the level of authority I wanted, either. I think, in a way, that’s why it’s easier to pounce on Cosby and rally around that injustice: Because when you have that many accusers, there isn’t much ambiguity. I also think it explains why we publicly crucify Kanye West, whose worst crime is being a dick, and not people like Allen or Polanski. The stakes are lower and it’s easier to feel like we’re on the right side of things. (I’m a pretty big Kanye apologist, because his sort of dickishness does feel like the sort of art-star eccentricity I can look past.)

I think we instinctually want to ignore things that make us uncomfortable. We want to keep our artists and athletes intact or attempt to insulate them from their wrongdoings so that we can, in a sense, insulate our own consciences. Jenni, I agree with what you said: Much of our fear about talking about these issues comes from the questions we end up having to ask about ourselves. But we can’t let ourselves off the hook that easily. We have to talk over this stuff. We have to wrestle with these ideas. We have to struggle the next time The Cosby Show comes on. If we don’t, then we become complicit on some level. That sounds cliche (If you aren’t part of the solution, you’re part of the problem!), but I believe it to be true.

Jenni

I like Roman Polanski movies. I do. And yet they are part and parcel of a man who thought he could help himself to a drunk and drugged teen who said no until she finally just sort of gave up so he could get it over with, and when he thought the terms of his punishment — a rap on the knuckles at most, especially given the insane milieu of Hollywood in the ’70s — wouldn’t be quite as amenable as he’d prefer, he simply left the country. What a privileged, demented jackass. And yet here I am, decades later, still marveling over Rosemary’s Baby. Even if you knew nothing about Polanski, by the end of Repulsion you’d be thinking, “Damn, this guy has some issues with women.” You cannot separate him from his movies. And yet.

So what I’m saying is, if you want to watch Woody Allen movies or Polanski movies or even The Cosby Show, well, that’s on you. And it’s on me. It’s on all of us, and it’s on the system that makes it easy for one person’s publicity machine to steamroll reporters and editors alike. There is no easy answer. It’s possible to see the beauty of Mike Tyson in the ring or to feel moved by the horrors he endured as a child, but still want to vomit when you see him in The Hangover or with his own goddamn Adult Swim show. People are complicated as hell.

That said, if you are a critic and you feel it’s your job to engage with Allen’s work without taking into account who he is as a person and the way his personal life intersects with the ongoing themes in his work, I’m somewhat concerned about your ability to compartmentalize, or perhaps empathize.

Vince

I have attempted to watch Woody Allen’s movies without bringing up his past when I’ve reviewed them, but if he keeps writing things that remind me of it, that’s on him. So, I guess, no, I don’t feel like it’s my job to compartmentalize to the degree that I willfully ignore the mental picture the art gives me of the artist. I’m not a computer program, and I don’t think it’d make for a valuable review if I tried to be. If the art makes me think better of him, I feel much more okay with giving it my attention.

Going back to what Steve was saying about the history of excusing artist’s eccentricities, I think we need to stop putting artists, and art, up on this pedestal where the creator is this font of mythical wisdom, this oracle. We do this all the time, where we put more stock in some guy’s take on world events because he was good at writing love songs (it’s especially bad with musicians — I think there’s a part of our reptilian brains that still thinks music is magic and musicians are sorcerers). It’s the idea of the artist as unknowable, which plenty of smart artists have been exploiting for years, cultivating eccentricities to give themselves mystique.

It’s always hard to separate the thing from the trappings of the thing. But I think the sooner we accept that making great art doesn’t make you a great person — we know that’s true when we hear it, yet often act otherwise — the less it will feel like betrayal when we find out an artist whose work we love isn’t.