When Leaving Neverland premiered at Sundance, I saw “four hour documentary about the Michael Jackson molestation allegations” on the program and almost immediately mentally marked it with a giant red stamp — NO THANKS. That just didn’t sound like something I wanted to sit through, a film to be endured rather than enjoyed.

The film was released on HBO this week, where it’s since become the network’s third-most-watched documentary in 10 years. I finally broke down and watched it, and while it turned out to be every bit as hard to watch as I’d imagined, it was even harder to turn away. Call it the new “cringe and binge” phenomenon. But certainly, it’s more than that.

I tend to resist watching movies that depict things I know are horrible simply in order to know that those things are indeed horrible. What Leaving Neverland offers isn’t just the notion that child sexual abuse is bad, repeated ad nauseam, it’s the promise of being able to at least start to understand the issue in its full complexity. And that’s just as compelling as it is “important.”

The two survivors it profiles — choreographer Wade Robson and computer programmer James Safechuck — aren’t shattered people, despite their trauma, and Jackson, even if we take the film at face value (and I mostly do), isn’t a perfect monster, despite having done some truly horrifying things.

It seems apparent now that our conception of child sexual abusers has been limited by our own understandable reticence to discuss child sexual abuse. If guilt and shame are at the root of the trauma from sexual abuse, we owe it to abuse survivors to be up to that discussion, to be game to acknowledge abuse in all its awful detail, no matter how much doing that sucks. Acting as if it’s too taboo to even think about only adds to their shame. It’s a credit to Leaving Neverland director Dan Reed and HBO that they were willing to go there, and to Wade Robson and James Safechuck for being able to recount their own abuse stories so earnestly and so coherently. That they were such compelling, relatable characters is one of the most powerful aspects of the movie.

In not only existing but becoming a phenomenon, what we used to call a watercooler topic, Leaving Neverland represents a collective step forward in how we see abusers and survivors, even from just a few years ago. It’s been little more than three years since the release of Spotlight, a story about the Boston Globe team that uncovered systemic sexual abuse by the Catholic Church, and even that best picture-winning movie consisted of about 95 percent investigating sexual abuse and maybe 5 percent the actual abuse, with a minimum of talking to abusers and survivors. There’s exactly one scene, where the team knocks at an old priest’s door, and he makes an offhand remark about how he was abused as a child, that even broaches the subject of how abuse is passed from one generation to the next. The matter is quickly dropped, never to be discussed again. (That lack of discussion being in itself a comment on how the pattern of abuse self-replicates).

Before that, our collective conception of pedophiles was probably formed in large part by To Catch A Predator, a show where sweaty pedophiles (or maybe just the pedo-curious) were entrapped and then confronted by Chris Hansen, in a perfectly tacky early aughts mash-up of Cops and Dateline NBC. To Catch A Predator was canceled in 2008, and Hansen unsuccessfully tried to Kickstart “Hansen vs. Predator” in 2015. (In January of this year Hansen was arrested himself for writing a bad check.) Coincidentally, Leaving Neverland director Dan Reed even seems to have directed his own version of To Catch A Predator in 2014 — The Paedophile Hunter, a TV documentary described as “A look at the work of Stinson Hunter and his gang who pose as underage girls in order to catch pedophiles.”

Before that there was the karate instructor, Jeffrey Doucet, shot in the head on live TV in 1985, by an allegedly abused son’s angry father, who subsequently avoided any jail time. It’s possible to view these pop culture events as signposts, marks on a timeline reflecting our societal capacity to discuss child sexual abuse at the time. If Leaving Neverland is the latest, over the past 34 years we would seem to have evolved from “just shoot ’em in the head and never speak of it again” to a four-hour documentary discussing pedophiles’ methods.

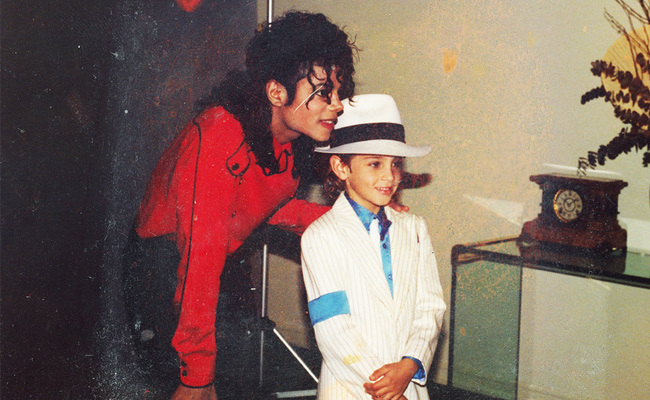

While Leaving Neverland isn’t much more in-depth than Spotlight about why its subject might abuse, the answers are written all over Michael Jackson’s face. Whatever happened to Jackson during his own childhood was so horrific that he spent the better part of his adulthood having his face hacked apart and rearranged so he wouldn’t have to see the same person in the mirror. It stunted him to the point that virtually everyone who knew him compared him to a prepubescent boy, well into his late thirties. Yes, those probably should’ve been important clues not to let a child sleep in his bed, but it’s ever amazing what flaws fame and success (AND MONEY!!!!!) can cover up (with all due allusion to Bill O’Reilly, R. Kelly, et al).

At its best, Leaving Neverland evolves our expectations of abuse survivors. Jackson’s cultish defenders (who are still legion, and I have the emails to prove it, despite never having written about this show before now) seize on the fact that Robson and Safechuck are “suddenly” changing their stories now, despite having denied all abuse allegations in the past, to paint them as liars, as money-driven opportunists, whatever. But the fact that Leaving Neverland‘s subjects had defended him in the past is probably its most salient factor. It explains how the relationship works and why abusers so often get away with it. If you take Robson and Safechuck at face value, and again, I mostly do (I would’ve liked to hear them explain the posthumous lawsuits a little more than the documentary does), Leaving Neverland helps explain abuse survivors’ complex series of motivations, and rich abusers’ wealth of options to shut them up, both legally and psychologically.

Both Robson and Safechuck explain that despite legitimate anger over the abuse, they were still worried about what would happen to their abuser if they told the truth. Would he get a lengthy prison term that he might not survive? Would he get tackled over a hedge by cops in windbreakers while being shouted at by Chris Hansen? Maybe a world where pedophiles are no longer shot in the head in an airport or tackled over hedges would make it easier for abusers to come forward. Or is the posthumous four-hour documentary just the 2019 version of a hedge tackle? It’s hard to know whether to treat abusers entirely as victims to be rehabilitated or as predators to be punished, because they tend to be both, and Jackson, like his counterpart in Abducted in Plain sight, seems to have exploited his own need for rehabilitation as a predation strategy. Leaving Neverland doesn’t solve this conundrum, but it leads us to a greater understanding of the issues at hand.

It also helps us understand why there are so often competing accounts of abuse. I always sort of assumed Michael Jackson was guilty, based on the admitted fact that he was a 30-something-year-old man who would regularly share beds with young boys, and because he was so clearly stunted, in appearance, in action, in pretty much everything. But every time Corey Feldman or Macauley Culkin publicly swore up and down that Michael Jackson had never abused them, I admit that I wavered. Corey Feldman hasn’t been shy about naming names, I thought, why wouldn’t he name this one? Maybe Michael Jackson didn’t sexually abuse any children. Maybe he was just extremely weird.

I, of all people, should’ve known better. A few years back, my old Little League coach was sentenced to a lengthy prison term for child sexual abuse. The fact that he wasn’t rich probably had something to do with that sentence, but he still managed to get away with it, allegedly, for 20-plus years. Now, this man wasn’t just my Little League coach. He coached my basketball team, was an assistant on my Pop Warner football team, and took us to Disneyland when we won the league championship the year I was 12. A few summers he drove me to and from the golf course on days when my mom was working. I spent a LOT of time with this man.

When he was arrested my reaction wasn’t entirely one of shock. He never abused me, but there was once a leg massage, borderline justifiable at the time, in theory — he was a physical trainer, I was a sore athlete — that definitely seems creepy in retrospect. In the years since I’ve thought a lot about why I was so lucky. I bandied about a few theories in my head. That I had a stable home life, that I had parents who never would’ve let me stay with him overnight or, God forbid, in the same bed. My mom even asked me straight out if anything weird ever happened on a few occasions. Like Wade Robson told his mom in Leaving Neverland, I told her no. Only in my case, it happened to be true. Which makes me wonder if my own explanations are… victim-blamey, a way to explain luck that was maybe just that: luck. I honestly don’t know.

But it also makes me think about Corey Feldman. It’s hard for me to imagine using my own experiences to invalidate some of my former teammates’. It didn’t happen to me so it must not have happened to them. I never made that leap. To me, it sounded plausible. It’s disappointing that even an abuse survivor like Corey Feldman wouldn’t be able to see beyond his own experience. Or am I just not seeing beyond mine?

Being unable to see beyond your own experience is hard. It’s also undeniably weird to be talking about pedophilia around the water cooler, but maybe that’s what we’ve needed. It’s always been a strange world — at least we’ve stopped pretending it’s normal.

Vince Mancini is on Twitter. You can find his archive of reviews here.