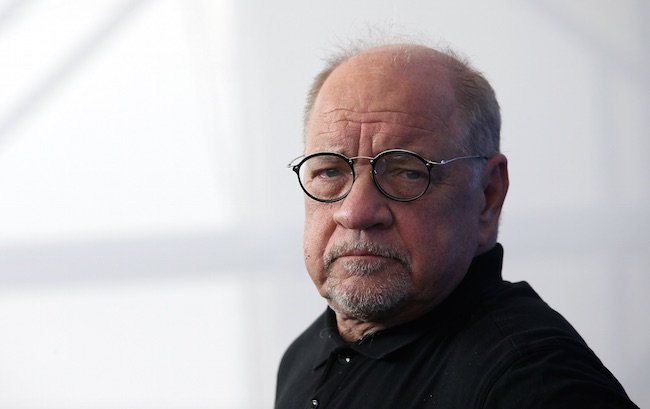

When you first meet Paul Schrader, you can’t help but feel like you’re being sized up a bit. It’s completely possible it’s all in my imagination, but it does feel like there’s a sense of, “I wrote Taxi Driver, who the hell are you?” (To be fair, he has a point.) But once you get to talking with Paul Schrader, this is a human being with some stories. Man, does he have some stories.

Like the one about how Jack Nicholson felt he was being lowballed for The Mosquito Coast, which led to an expletive-fueled dialogue. Or the one about how Bruce Springsteen “stole” the title of a Schrader’s screenplay called Born in the U.S.A. And then there’s the one about how Schrader feels Steven Spielberg still at least owes him a Rolex for the work he did on Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Schrader’s latest film, First Reformed, is getting the director-screenwriter some of the best reviews of his career. The film stars Ethan Hawke, who plays a small-town chaplain named Toller, who meets a pregnant woman named Mary (played by Amanda Seyfried) whose husband wants her to terminate the pregnancy because he can’t live with the thought of bringing a child into a world that seems environmentally doomed. This encounter permanently changes Toller’s worldview. It’s a minimalist film, with no score and hardly any camera movement. As Schrader says, he wanted to see what he could get away with by doing as little as possible.

Ahead, Schrader discusses how he views films today. Basically, would a movie like Taxi Driver even play at a local multiplex in 2018? He has many thoughts about this. And, yes, he has stories. Man, does he have some stories.

A large plot point of First Reformed is that a man doesn’t want to bring a baby into a world he thinks is being destroyed. Not to that extreme, but I understand that sentiment. At least I want to see how this Trump situation pans out first…

It’s sort of staggering to realize that young people are having these thoughts in a time of relative prosperity, as opposed to a time of starvation or war.

Is that something you wanted to explore? You’re right, we’re not living in the Great Depression…

My generation was born into the sweet spot of history – in terms of leisure time, prosperity, all of that. My parents’ generation, the Greatest Generation, lived through a depression and a war to give us this opportunity. And we became, as a result, the selfish generation. I saw that Tom Wolfe died, who coined the term the “Me Generation.”

Is that the disconnect? Boomers still think things are like they had it?

Well, for 10,000 years mankind has been having a hypothetical discussion of why we are here and what will become of us. But it was always hypothetical. Now, for the first time in human history, it’s starting to sound not so hypothetical. But you have to make the decision to hope. You have to hold that in your head, otherwise you can’t live.

Is this movie about hope?

I’m not sure. I’m not very optimistic. In fact, I’m not optimistic at all.

I was feeling inspired by what you said, and now you’re saying you’re not optimistic…

You can choose to hope, even if you don’t have hope.

You had some complications with some prior recent films, but now you got to do what you wanted on this and the response is very positive?

[Laughs] Well, when I got final cut on Dog Eat Dog, I used that freedom to just do whatever I felt like and go gonzo. And then I got this film and I thought, what else could I do with that freedom? I can use the freedom not to do things. Not to move the camera and not have music – and use what I call “the scalpel of boredom.”

You’ve mentioned that it was harder to get a movie made in the past, now anyone can do it but they don’t make money. Which way is better?

You know, we have democratized filmmaking. It used to be a very elitist business. Now it’s the same as painting or poetry or music. Anybody can do it. If you’re 12-years-old and haven’t yet figured out how to make a movie, you’re behind the curve. So, now, we are in the same predicament as the other arts. What percentage of painters make a living? Or musicians? So now it’s quite possible to make a film for $25,000 and not get paid and to lose all $25,000. In the past, if you made a movie, you got paid. Now you can make a movie and not get paid!

But out of those we get things we wouldn’t have seen before. You’re right, there’s a lot of noise, but every now and then…

More than every now and then. We are seeing a bumper crop of good first films from directors who normally would not have had that opportunity. And you read the trade papers and one review after another, “terrific first film!” Well, where did this come from? It came from technological freedom.

Where does this end? People are going to have to make money eventually.

Well, there is a bubble. But hopefully it will correct itself. But I have been hearing for many years now that Netflix is not a sustainable model. But it is a sustainable model!

Every time they release their earnings they seem to be doing pretty well.

And they can pour $140 million into Scorsese’s new film and not think twice about it.

So what’s your opinion of that? Purists don’t like where this is going, but they are giving money to people…

Well, what I feel about First Reformed, I felt that it was important that the conversation start with people who saw it in a theater – the festival circuit and critics. Then if someone wants to watch it at home, they know the rules. They know it’s a slow movie and that it’s a serious movie. So if someone decides to watch it at home, they are going to give it a shot.

I disagree when people say things like “You have to watch the new Avengers in a theater.” And I like those movies, but no you don’t. It’s the movies that need your complete attention with no distractions that should be watched in a theater.

Unless you make that commitment that you can do that at home. If you have a flat screen and a sound system and a dark room, you can do it at home.

Would Taxi Driver be in theaters today?

Well, First Reformed opens on Friday.

That’s a good point. But I mean the local Midwestern multiplex.

Well, there are three kind of movies now – and the middle has fallen out. So you have children’s movies, spectacle movies, and arthouse club movies. And they are doing quite well, the arthouse club movies, so there’s still a place for that. What’s run out of steam is the general multiplex movie that you don’t really feel you need to see in a theater – unless you want to get that hit because you want to take your kids and see them interact with other kids. Or you want to get that hit because it’s Black Panther and you want to see how it plays in front of an audience. Certain movies, like Get Out, you make a point to see with an audience.

Right. The cultural phenomenon still happens, but it’s rare…

Yeah, you know, I see most things on TV, like everybody else. And there are things that are better on TV than in a theater. I wouldn’t want to see Wild Wild Country in a theater. I wouldn’t want to sit there for six hours. I’m glad it was six hours long, but I’m glad I could watch it at home.

It’s not like we are sitting at home with three-by-four CRT televisions anymore. You can get a good experience at home.

Yeah. And often better. One of the theaters down at the IFC is a flat screen. And with my prints, if they can get a good DCP, I’d rather have that than one of my battered up old prints from UCLA.

For me, the most fascinating stretch of your career is when you wrote The Mosquito Coast, directed Light of Day, then wrote The Last Temptation of Christ all in two years. Those are all very different.

Well, I kind of like the Kubrick model. Any time Stanley would do something, it was time to figure out a new problem – a new solution to a problem he had to solve before, whether that was Barry Lyndon or A Clockwork Orange. And then there’s the Hitchcock model where you’re just refining your films. And I like this idea of let’s do something we haven’t done before. That was the whole appeal of Canyons, can I actually do this? Can Bret Easton Ellis and I make a film together? And we pulled it off. We did. And then Dog Eat Dog, what can I make a gangster film look like in 2016? Can I make a Tarantino-type film? What would it look like if I made it? And then this, going to a cold style, a recessive style. Dog Eat Dog comes at you like crazy and this one keeps pushing away from you.

When you wrote The Mosquito Coast did you ever picture it as a Harrison Ford movie?

Saul Zaentz had done One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. And he was doing The Mosquito Coast for Jack Nicholson. And he felt Jack owed him a favor and wanted to get Jack at a price. Jack says, “Fuck you, I don’t owe you a favor. Here’s my price.” Saul was offended and said, “fuck you,” back. And he went over to Harrison Ford and gave Harrison Ford the same amount of money he would have given Jack.

Were you happy with how it turned out?

Yeah, I mean, I was a little thrown because the character had that Jack Nicholson thing – that bombast and that confidence that I can talk you into anything. Yeah, I haven’t seen it since it came out. But I don’t go back.

Light of Day seems like such an offshoot movie for you.

I made one film about my mother and I made one film about my father. And I think they are two of my weakest films. Light of Day was about my mother and Hardcore was about my father. I think I was maybe writing too close to the vest. I’d much rather work with these metaphors like a taxi driver, or a drug dealer, or a minister then that type of family situation.

You got a great Bruce Springsteen song out of it.

Yeah, when he first started doing “Light of Day” onstage he’d do a shootout to me. Well, you know how that all came to be? I had written a script called Born in the U.S.A.…

Oh yeah, I read his book and he mentions this…

And as he told me later, he made a decision not to do movies. He didn’t want to give up that much control. And he said, “I never did read your script, but it was on my coffee table for a month. And I was working on this song about Vietnam and I thought ‘Vietnam’ was not a good title for the song. And every time I walked across the room I saw Born on the U.S.A., so I stole it.”

I’m pretty fascinated by your script for Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Well, it’s an interesting thing. Michael Phillips and Steven Spielberg approached me and I built the script sort of on the model of Saint Paul.

Did they ever tell you what they wanted? I’ve always wondered why it was so different.

They wanted a film about a debunker who became an apostle type, and that’s Saint Paul. He’s out there and has a vision and turns around and tries to be the first man to leave this Earth. And so that’s sort of what it was. Steve and I had an argument about it. And I remember I said to him, “I refuse to write a script about the first man to leave our planet in order to go to another place and set up a McDonald’s stand.” And Steve says, “That’s exactly what we wanted.” [Laughs] Great. So he wound up with a much more populist character. And I had an elitist character. So that was the dividing line. Then I was told repeatedly that the movie was nothing like my script, so I didn’t ask for a credit. Then I saw the movie and I’m like, “Hmmm, that’s familiar. That’s familiar.”

Was there ever reconciliation?

No. Years later, I said to Michael Phillips, “You know, Steve never really thanked me for that. Ask him to give me something. Ask him to give me a Rolex.” And then I never heard back. Then I said to Michael, “Did you ever ask?” Michael says, “Yeah, I asked. He said no.” [Laughs.]

You can contact Mike Ryan directly on Twitter.