Conflicted, the debut film from indie Buffalo rap label Griselda Records, is not an example of great cinema. To its credit, it isn’t really trying to be. It is a fairly standard tale of street life, following the pattern set by the label’s music from rappers Benny The Butcher, Conway The Machine, and Westside Gunn. It’s also a relatively serviceable vehicle for the group’s music via the film’s soundtrack, which plays over about half its scenes, showcasing crew’s collaborations with artists and producers from outside their usual, self-contained circle. They even sport their own merchandise in the movie, despite two of the three core members actually starring in it as pivotal drivers of the plot.

In that way, though, Conflicted is more than just a two-hour long commercial for Griselda’s latest compilation. It’s a part of a proud tradition within hip-hop of rap labels independently producing their own films, just because they can and just to say they did it. Cash Money Records, No Limit, and Roc-A-Fella Records have all bypassed the major studio system and Hollywood itself in order to put people in the producers, directors, and actors’ chairs who might never ordinarily be afforded the opportunity to say they made a movie. While the quality of these films varies wildly, in their own ways they are classics to those of us who grew up looking up to these rappers, producers, and flashy music executives who came up in the places we did and told stories that were familiar to us, if not extravagantly crafted.

When Master P and No Limit Records released I’m Bout It in 1997, no independent rap label had ever attempted anything like it before. While there had certainly been films about hip-hop and starring rappers, such as 1985’s Krush Groove and Run-DMC’s Tougher Than Leather in 1988, these films were produced by professional film studios (Warner Bros. and New Line Cinema, respectively). They starred rappers and told stories similar to those of the artists’ music, and they were made with relatively big budgets and distributed via traditional means, screening in theaters nationwide as a way to recoup what ultimately amounted to elaborate marketing campaigns for the artists featured therein. They even both feature extended performance sequences, making them more like musicals or even super-extended music videos designed more to show off the music than any of the featured players’ acting chops.

This isn’t to say that when I’m Bout It hit the streets, it was hailed as a cinematic masterpiece. The film barely has a Rotten Tomatoes page to this day as it garnered few if any professional reviews and released directly to video, preventing it from making a splash at the box office. But, as noted in a 2017 retrospective in the Houston Press, it was an achievement for other reasons. The audacity of Master P’s gamble — creating a low-budget, feature-length film, written, starring, and directed by what was effectively a bunch of amateurs — paid huge dividends when it came to brand building. Suddenly, No Limit Records wasn’t just an underground rap label from New Orleans. It was a bonafide multimedia conglomerate — at least, in the eyes of the rap media who covered the film and the fans who ate up the $20 copies of the VHS tape at record and video stores upon its release.

I’m Bout It proved that it could be done and that there were benefits behind doing it. While sales figures for the film are nonexistent, it almost certainly turned a profit; today, it can be found in the Turner Classic Movies library and streamed in the “Black films” sections of streaming services like Tubi. Licensing the rights to the film is undoubtedly lucrative when compared to its obviously minuscule budget, but more importantly, it’s fondly remembered by a generation of hip-hop fans as our own, hood Criterion Classic. Not only was No Limit able to follow up the success of I’m Bout It with a string of similarly low-budget releases throughout the late ‘90s and early 2000s, but the proof of concept was also enough to get one of those films, 1998’s I Got The Hook Up, a theatrical release through Dimension Films. It grossed over $10 million at the box office on a budget of just $3 million. It’s also important because it was the wedge that opened the door for other rap labels, while the promise of similar successes tantalized them to follow suit.

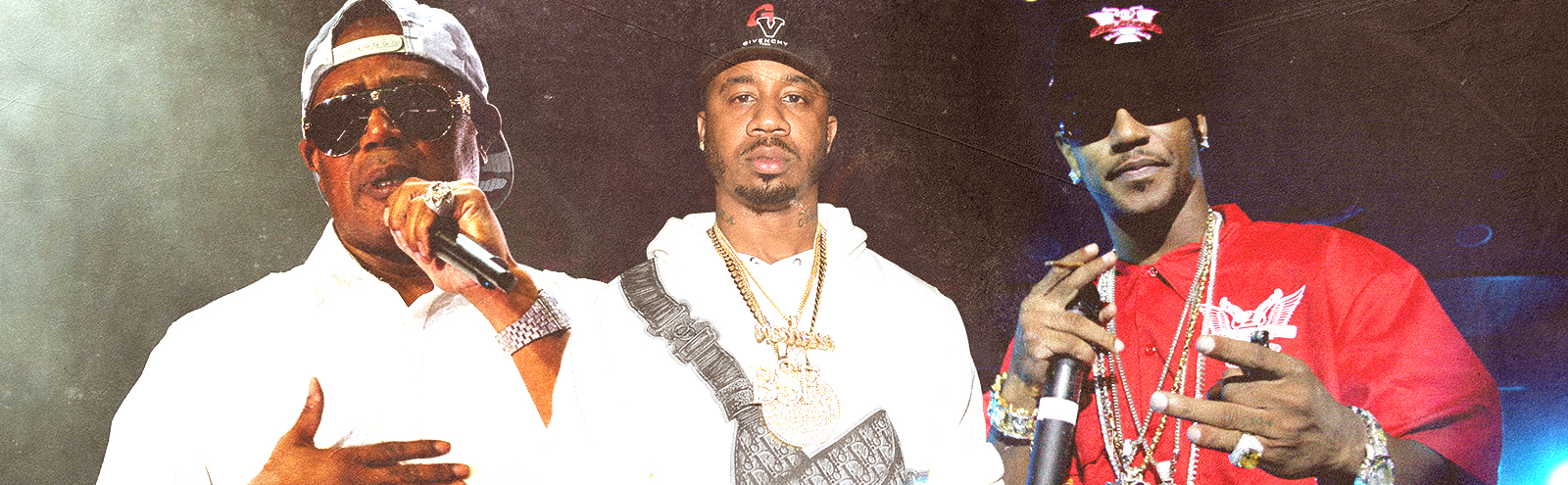

Soon, Roc-A-Fella Records, the then-burgeoning brainchild of Dame Dash, Jay-Z, and Kareem “Biggs” Burke, had its own string of cheaply-made crime dramas out in the world, beginning with 1998’s Streets Is Watching. While that film strung together Jay’s music videos into a tenuous plot, the group truly nailed narrative storytelling with a spate of movies released over the course of the early 2000s. With State Property, Paper Soldiers (the film debut of Kevin Hart), and the label’s magnum opus, Paid In Full, Roc-A-Fella proved that low-budget didn’t have to mean low-quality. That isn’t to say that all those films were “good,” per se, but they made money, added prestige to the label’s slick presentation as a big-budget, well-rounded enterprise, and continued to put independent filmmakers to work without waiting for a say-so from a Spielberg or a Bruckheimer. The stories were ones that spoke to the inner-city experience, from the perspective of people who lived it. And one of those stories became the standard against which plenty of these narratives are compared to this day.

Paid In Full, the 1980s crack-era period film Roc-A-Fella released in 2002, is the very definition of a cult classic. It was also the moment the Roc put it all together and made a movie that could stand the test of time. Directed by Drumline’s Charles Stone III, the film displays a polish that critical favorite hood classics before it had while maintaining the grit and realism of its indie rap label-produced forebears. It also smartly put established actors in the lead roles, with Mekhi Phifer and Wood Harris depicting Mitch and Ace, the twin cores of the film, and relegating its sole rapper, Cam’ron, to a supporting role that made the best use of his talents. Rather than demanding drama or stoicism, Cam is allowed to be funny, to show off the personality that made him such a charismatic figure of aughties rap.

The laughs here were intentional, unlike in many other hood movies, making them a modern-day fixture of social media meme-ology. With endless quotables now seemingly on the tips of hip-hop fans’ tongues at a moment’s notice (my personal favorite: “N****s get shot every day, b”), Paid In Full occupies a unique position in the continuum of hip-hop’s everlasting flirtation with the silver screen. It was a lesson Roc-A-Fella took into its State Property sequel a few years later, allowing Beanie Sigel to play up the funny and N.O.R.E. to portray a character named — I shit you not — El Pollo Loco. It’s a lesson more of these films could stand to learn. A little levity lightens up the grim fare and allows rappers to be entertaining, bringing the charm that makes us fall in love with them on records to the screen.

So, where does Conflicted land within this continuum? Look, it’s no Goodfellas. More of the movie is given over to the characters delivering wooden, on-the-nose dialogue about their emotional states and the film’s themes than actually showing us these things. The music, while meeting the usual Griselda standards, isn’t very well utilized, either blaring over montage sequences just randomly blasting in the backgrounds of scenes where no dialogue needs to be heard (and it’s pretty on-the-nose too). And there’s a truly ill-advised rape scene that could have been left on the cutting room floor along with a lot of filler shots. But the point isn’t to make great art, despite the protestations of Westside Gunn (if you’re reading this, please, no smoke is required) and the rest of the Buffalo cohort. The point is that they made a movie that showed the world Buffalo in all its glory and downfall, right down to their consonant-mangling accents (hearing one character refer to her business card, then the library discombobulated my brain for a full thirty seconds). It’s a story that couldn’t and wouldn’t be told any other way. It’s the story, for better or worse, of Griselda Records, and in that, it’s a triumph.