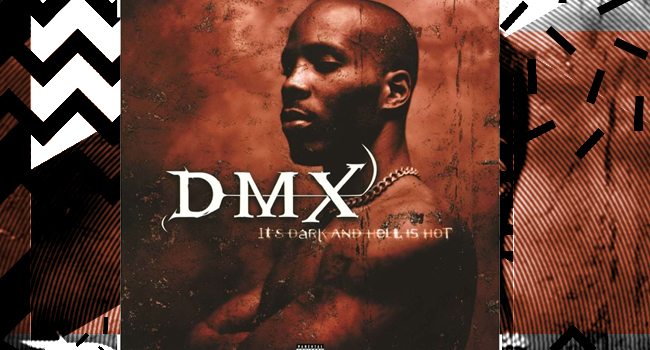

20 years ago, Earl Simmons looked death in the eye. To be honest, I’m not sure who won, or whether it matters. The staring contest itself is the point; it’s entertaining and harrowing and bizarrely motivating. It’s instructive of how trauma works, how it perpetuates itself, how it affects its victims. The fear, anger, and cold-eyed self-analysis that permeate DMX’s It’s Dark And Hell Is Hot didn’t change the way hip-hop is viewed as art — it smashed the lens then burned the canvas, removing the constraints of the form.

It cracked open X’s head and provided a sometimes demented tour of his inner struggles with faith and survival, but it also shifted hip-hop’s prevalent paradigm all the way to the left, creating a new set of rules for the next generation of the culture’s adherents to follow — and, at times, break themselves. Released on May 12, 1998, this album is still impacting the world of hip-hop two decaded later.

When It’s Dark was released, nobody thought anything so harsh, so blunt, so raw could sell — true story. While Puff Daddy and Bad Boy Records opted to sign the significantly smoother and broader-appealing Lox, Def Jam, Roc-a-Fella Records, and Irv Gotti’s Murder, Inc. all passed on DMX’s guttural snap, as Gotti has reminisced in interviews. DMX, who barked, growled, and menaced like a literal unleashed pitbull in adlibs and attacked his flow with visceral aggression that masked the dispassionate delivery of serial-killer-scary lines about murder, robbery, and drug sales, among other unsavory activities, seemed a man out of step with his time and place. Rap in 1998 seemed to demand stiletto slickness. DMX was a baseball bat wrapped in barbed wire — blunt, brash, prickly, and raw.

If the prevailing narrative of rap’s forking methodologies is one of a bifurcated system wherein mainstream went glitzy, glossy, jiggy, and bright while underground became conscious, cerebral, and down-to-earth, DMX’s sudden, surprising success on the back of downright evil, gully material like “Get At Me Dog,” “Crime Story,” and “N—-az Done Started Something” provided a third, jagged path. With a voice full of gravel, a heart full of regrets, and a veteran soldier’s dissociative observation, DMX detailed horrors and confronted demons, and didn’t often get the best of them.

Yet, It’s Dark And Hell Is Hot improbably reached No. 1 on the Billboard 200, turning DMX into a sensation. It was impossible to go anywhere in 1998 without hearing the strident call of Swizz Beats’ strangled synths and X’s emphatic exhortation to “Stop! Drop! Shut ’em down, open up shop!” That It’s Dark was paired with the more introspective, but no less murky Flesh Of My Flesh, Blood Of My Blood less than six months later and that it too went No. 1, turned DMX into a legend, an unstoppable dynamo that owned 1998, solidifying his grip on hip-hop’s conscious.

20 years later, the list of rappers who’ve adopted some aspect of DMX’s intimidating persona into their own is extensive: 21 Savage, Chief Keef, Lil Durk, Fredo Santana, and other goonish, ghoulish rappers have adopted DMX’s cold-eyed menace as part of their aesthetic and his unflinching darkness and plainspoken-but-nightmarish storytelling into their arsenals. However, even some of hip-hop’s most angelic voices have a bit of the sinner Earl Simmons in them. Kendrick Lamar’s DAMN. has been lauded as a master work examining Kenny’s relationship to his faith, his faith to his newfound success, and himself to the responsibilities to the world at large that both placed on him. It also doesn’t happen without It’s Dark And Hell Is Hot.

By his own admission, Kendrick’s flow is inspired by DMX’s, and his content parallels X’s in some crucial ways. When Kendrick depicts a symbolic embodiment of the devil through his Lucy character on To Pimp A Butterfly, he’s taking a page right out of DMX’s playbook on It’s Dark as he barks, “I sold my soul to the Devil, and the price was cheap / Ayo, it’s cold on this level, ’cause it’s twice as deep,” on “Let Me Fly.”

The price may have been cheap, but it seems as though the ultimate cost may have been too high for the DMX. Once a fearsome antihero projecting his threatening aura twelve feet out from his physical frame, in 2018 DMX is gaunt and no less haunted. He’s been plagued with tax troubles, hounded by paparazzi, and spent the better part of the last 18 months in and out of both jail and rehab.

Soon, he will be remanded to the custody of the state to serve a year in prison for tax evasion and upon his release, he’ll be expected to repay over $2 million in back taxes. He may have lost his way cutting rap’s third path, but for a generation of rappers who followed in his footsteps, from 50 Cent to Kendrick Lamar, he serves as both role model and warning. Hell is indeed very hot, and the devil always comes for his due. DMX may be paying for his sins, but his enduring legacy will always be his endless grasp for salvation.