The lonesome friends of science say / the world will end most any day / well if it does, then that’s okay / ‘Cause I don’t live here anyway. — “The Lonesome Friends Of Science”

I don’t believe in God anymore, but I still believe in John Prine.

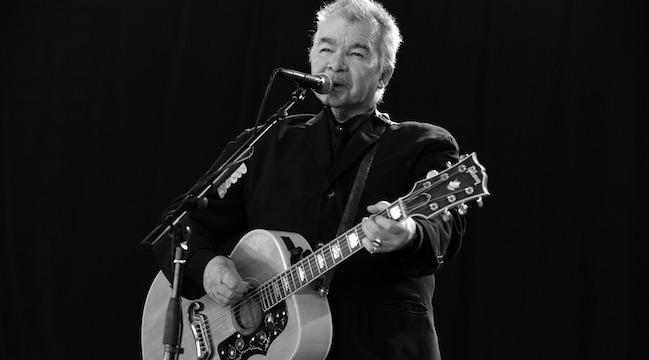

Like most eternal truths, I discovered Prine by accident, and the scenario where I did so is practically out of a song he’d write. On a trip to Alabama, taken on a whim during an ill-advised stint in grad school back in 2011, I caught him on a double bill featuring Emmylou Harris, who was legend enough to get me shelling out for a ticket without knowledge of the other headliner. Harris played with her own spectacular blue Kentucky ease, but it didn’t matter, by the time I left Birmingham that night Prine had effortlessly eclipsed any other reason for the trip. It seemed like discovering him was fate, but ultimately it proved to be something better — sheer, random chance in an uncaring universe.

Back then, an aspiring songwriter, I assumed any successful artist was better than me by virtue of their art. But the best thing about discovering Prine’s oeuvre during that lonely, isolated period of my largely unsuccessful post-grad studies was his knack for reveling in his own worst instincts — or maybe just admitting that he wants to. Strangely enough, those instincts ended up sounding smarter and smarter to me as time went on: Blow up your TV, throw away your paper…. try to find Jesus, on your own.

There’s a trace of the divine in a writer who never flinches away from his own grinning, crooked humanity and the bitterness that so often readily accompanies it. “I hate graveyards and old pawn shops / for they always bring me tears,” he sings on the stunning early-career hit “Souvenirs,” adding: “I can’t forgive the way they robbed me / of my childhood souvenirs.” This is not a sentimental collector fending off death by fetishizing the past, but a grieving human, mourning the loss of precious memories. Novelties are a pit stop for those who can’t let go of time; Prine turns a trinket into a totem by acknowledging what it forever lacks — the record of our interior lives. Luckily for us, that’s exactly what his songwriting provides.

On his latest album, this year’s The Tree Of Forgiveness, John sings of how much he wants to get to heaven… so he can smoke a cigarette again. He’s faced and survived two bouts with cancer; his idea of heaven is still a cigarette. This is emblematic of the reason he’s such a beloved songwriter, because he refuses to stop short at an easy chorus, necessarily following it down to its harrowing conclusion, but he won’t wallow in despair, either. In heaven, his cigarette is a joyous affair, free of any gruesome side effects, the smoke stretches on for nine miles.

A Midwesterner through and through, Prine is a country philosopher who writes and moves with big-hearted absurdity, the kind that already defined my own choices, for better or worse. Unlike plenty of his folk-leaning contemporaries, his songs were full of pervy admissions (“caught him once and he was sniffing my undies,” from “In Spite Of Ourselves”) and uncanny observations (“Jesus don’t like killing, no matter what the reason’s for,” from “Your Flag Decal Won’t Get You Into Heaven Anymore”), a far cry from the shimmering, esoteric verses of Dylan or the simplistic, beautiful descriptions that defined the more pastoral traditions. Working as a mailman until Kris Kristofferson discovered him at 25, Prine often sounds like an ornery upstart getting away with something — except his tender poeticism inspired even a great like Dylan to solemnly back him up on harmonica, or so the legend goes.

For the last seven years, that sole concert in Alabama was my single interaction with the man himself as a performing force. Because, you can listen to John Prine recordings, but there’s a rare, inimitable presence that accompanies his live show, whether that’s the rambling, ludicrous stories he tells between songs, or the effortless humility he uses to imbue his saddest material with deadly gravity. A 2010 recording called In Person And On Stage has been a near constant companion for my own journey through Prine fandom, a collection of his greatest hits recorded live, with both the grief and giggling, between-song banter caught on tape.

“Fiona, this is for you — she is my everything,” he declares on that album, before launching into a song of the same name, and that joyous adlib becomes part of the song’s fabric, as necessary as any other note or lyric. The song sounds naked to me without it, now. There isn’t a trace of doubt in his voice, and that same certainty carried into his voice last Friday night, when Fiona herself joined him on a stirring encore toward the end of his show at the Theatre At Ace Hotel.

Aside from dueting with his wife, Prine has a long history of working other female voices into his show, including Emmylou and the wily Iris Dement, who appears on four songs off his 1999 album In Spite of Ourselves, the first album he released after beating cancer for the first time. He repeated that act recently, in 2016, with For Better Or Worse, enlisting young talent like Miranda Lambert, Holly Williams, Morgane Stapleton, and Kacey Musgraves to tackle an array of country standards. It’s the kind of move that stands in direct contrast to a modern country machine that allows men to achieve superstar success while simultaneously shutting women out, but of course, John Prine has never had any use for Nashville’s monolith.

At the Ace, he also used his platform to spotlight another voice, that of the cult R&B figure Jerry Williams, Jr, aka Swamp Dogg, who covered one of Prine’s own biggest hits, “Sam Stone,” to great effect years back. The two perform in such different vocal ranges that it was impossible for them to duet on the track, instead taking turns on the song’s verses about a morphine-addicted veteran, both men delivering the chilling one-liner of the chorus — “there’s a hole in daddy’s arm / where all the money goes” — with their respective emotional shrapnel embedded.

“This man is one of the greatest writers, he tells stories that are just… a monster,” Swamp Dogg pronounced, after delivering a longer sermon on the plight of the homeless, particularly veterans, and solemnly shaking the hands of everyone in the band he could reach while shuffling back off stage. Swamp Dogg is a relic of another time, and perhaps it was his appearance that cemented just how rare it is for someone of Prine’s stature (and age) to still be able to deliver a two-hour set to a packed venue on a Friday night in Los Angeles.

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bi9cGWulBUz/

Not only that, but to do it with such devilish disregard for his own age. There is an innocence to Prine’s continued appearances that is akin to youthfulness, a sort of ageless swagger that has long defined the threads of American rebellion and independence that still feel worth celebrating. On the final song of his set, the rollicking, meditative “Lake Marie,” a seven-minute-plus song that willfully exemplifies the live elements that define Prine’s ethos, the man, a veteran of 71, threw down his guitar down, did magic moves at it, flipped up his suit coat, turned around and showed his ass to the audience, shaking it back and forth like a kid, taunting a foe. Then he traipsed offstage, while his band carried the song to its naturally peaceful conclusion.

A father and son duo sitting in front of me exchanged laughs over this unexpected yet wholly welcome display and then pored over the recent setlist they’d printed off, consulting it to see what he’d left off, what might be in store for the encore. This is the kind of fervent fandom we’ve come to expect of teenage girls at Beyonce and One Direction concerts, but it was just as present here, at an old cult country star’s umpteenth go at things. Young people are welcome at Prine shows, and though there were small bunches of us amid the swathes of older folks, even when he was in his own prime, John is the rare songwriter who treats the elderly with veneration, hell even adoration, in his work.

Despite the raucous finale, the show’s most stunning moment came in the first third of the show, a riptide of emotion that was never surpassed on the lonesome “Hello In There.” A song of tribute to the eighty-plus crowd, whose kids are grown and whose routines are so repetitive they register as a forgotten dream, a shadow of a younger life. Prine’s song insists that there is something beyond valuable in these lives, that those of us on the outside should step into their world, be it even for the briefest moment, to say hello. He wrote that song when he was young (and calls it his favorite song he’s ever written), an outsider moved by a plight he witnessed, but there’s a companion track on his new record tells the story from the inside out: “The lonesome friends of science say / the world will end most any day / well if it does, then that’s okay / ‘Cause I don’t live here anyway.”

Both songs are concerned with universal truths that center humanity, even when existence on earth itself is fraught, boring, or borderline meaningless. Regardless of age or loneliness, they insist on the dignity of humanity, an infusion of grace that is saintly, devotional even. In his universe, heaven exists in service of a cigarette, forgiveness is a tree that grows, scientists are just the snobby fools who exiled Pluto from the planetary dance. And so, if there is no God, Prine is proof that it doesn’t really matter, divine intervention will come to us daily anyway, in an acoustic guitar lick, in a sweep of ordinary blue, in an old man with the heart of a child. God is where you find him; he lives in a John Prine song. Hello in there.

The Tree Of Forgiveness is out now via Oh Boy Records. Get it here.