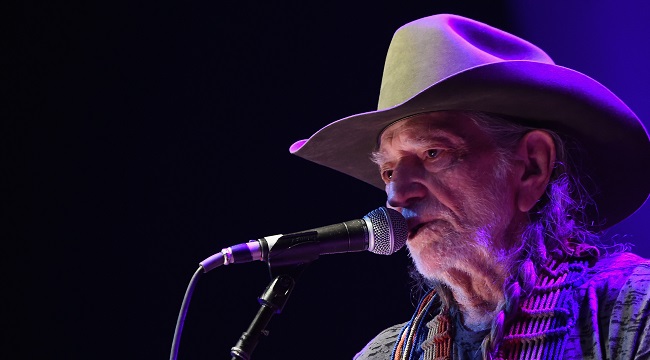

Whether you’re a flannel-wearing hipster who listens to The Avett Brothers on repeat during a daily bike commute, or a red-in-the-neck redneck who thinks Toby Keith’s “Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue” is second only to “The Star Spangled Banner,” you know at least two things about modern country music. First, that much of it owes its existence to the long-running public television music program, Austin City Limits, and the two-weekend festival it inspired. And second? Neither the show nor the festival would have happened without Willie Nelson.

Born in the small north Texas town of Abbott on April 29, 1933, Nelson made his first musical marks in Nashville throughout the ’60s and early ’70s. However, the singer-songwriter was never completely satisfied by the famous country music scene in Tennessee, so he semi-retired in 1972 and moved to Austin, Texas. That’s when the so-called “Outlaw Country” subgenre was born — a movement whose hippie influences and musical menageries were enticing enough to bring Nelson back on stage.

Nelson’s popularity soon began to skyrocket, especially when he and other progressive country music acts attended the 1972 Dripping Springs Reunion and the Fourth of July Picnics it inspired. As Nelson’s appeal grew, so too did other venues’ desires to feature him at their events or on their television programs. According to Tracey E. W. Laird, author of Austin City Limits: A History, this attraction “culminated in a late 1973 live production featuring Willie Nelson, Michael Murphey, and the [Armadillo Country Music Revue’s] house band, Greezy Wheels.” The performance was simulcast in Austin and San Antonio by the latter’s PBS affiliate KLRN. That’s when program director Bill Arhos, the man who would become the main driving force behind ACL, entered the picture.

Arhos, who joined KLRN (and then its Austin spinoff, KLRU) in 1961 and worked his way up the ladder, wanted to respond to PBS’ “push for KLRN to create programs of NOVA-size stature.” Public television in the Texas Hill Country didn’t have the budget that NOVA‘s home station in Boston did, so Arhos acquired $13,000 in grant funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and set out to create a new live music program.

Depending on what you read, a lot of people had a hand in inspiring and creating ACL. Laird notes that Arhos named local writers Jan Reid and Joe Gracey as the parties responsible for suggesting the idea. However, per the program’s official website, the program director “hatched the idea” for the show with director Bruce Scafe and producer Paul Bosner. Scafe brought his experiences from directing another public television music program, The Session, for WSIU in Carbondale, Illinois. As for Bosner, his fandom for the progressive country music scene in Austin is what turned Arhos onto the subgenre and determined ACL‘s focus. He also inspired the title, because he “saw the sign every week when he commuted from Dallas to Austin” for work.

Yes, all of this matters if you truly want to know who helped usher Outlaw Country onto the televised (and later nationally syndicated) stage, but there wouldn’t be a live music program if it weren’t for the music. Arhos and his team needed a pilot to show PBS, so on October 13, 1974, they filmed one with then-progressive country big shot B.W. Stevenson. Laird quotes a TIME magazine article that at the time named Stevenson “the most commercially successful of the young Austin musicians,” which was true, but it wasn’t enough to populate the studio with an audience big enough for the cameras. Arhos “scuttled the show” because of the poor turnout, though the ACL website suggests “the recording was deemed unusable.” Either way, they still needed a pilot.

So they booked Nelson the following night, October 14, and recorded a second pilot. Stevenson might have been more “commercially successful,” but Nelson’s appeal in Austin and the surrounding region was guaranteed to draw a large crowd to the venue for taping. According to the New York Times, Arhos had $7,000 left for the second round, but that was plenty of money for putting on a concert and filming the results. Besides, as Laird explains it, ACL only pays its artists “union scale.” That’s how a PBS affiliate was able to afford the likes of Stevenson and Nelson for two back-to-back concerts, as well as how the show is still able to afford the talent it attracts over 40 years later.

For a solid hour, Nelson and his band mates played 16 songs for a live studio audience that was almost too big for the venue — especially because stands were put behind the stage to accommodate the numbers. The then-41-year-old singer belted out older tunes like the 1970 hit “Bloody Mary Morning” and the more recent “Whiskey River,” which would go on to become a modern country classic. It was a lot of music for what seemed like such a small endeavor at the time, especially because the production wasn’t exactly equipped with the best video and audio equipment by the day’s standards, but that didn’t matter. The homemade quality was by design, and Nelson loved it.

So much so that he agreed to help Arhos raise money and awareness for the ACL pilot during his 1975 tour. According to Clint Richmond’s Willie Nelson: Behind the Music, which was based on the VH1 series, spent time at PBS affiliates throughout the country. He performed at station pledge drives, offered clips from the ACL pilot and spoke up about the show whenever he had the chance. Arhos did the same, albeit in a more direct manner with the top brass at PBS. He offered the pilot as part of the 1975 pledge drive, sent tapes to fellow program directors and general managers at other stations, and fought for as much exposure as possible.

The result? PBS picked up ACL in 1976 and provided the team with enough funding to invite more acts, big and small for 10, 60-minute episodes. Arhos was, as the Austin-American Statesman put it when he died in 2015, the “driving force” behind its initial and continued success. However, Nelson didn’t stop his association with Austin, the KLRU family and the television show that broadcast his music onto a much larger national stage. Quite the contrary, as he would return to perform on the program eight more times — including for the 40th anniversary special in 2014.

As Laird concludes her book’s section about Nelson’s relationship with ACL, “the pilot’s timing coincided with Nelson’s far-reaching critical buzz in 1975 and placed [the show] right there with him in his uniquely hip corner of the musical universe.” From the mid-’70s and on, both Nelson and the once-fledgling local music program exploded onto the national stage, where they both remain decades later.