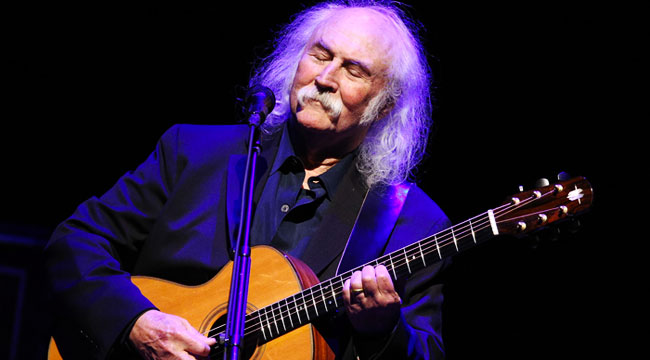

When David Crosby phoned last week for an interview, he immediately apologized for calling five minutes late. A slight lack of punctuality is hardly unusual for a musician, but the 77-year-old rock icon believes that every second is precious these days. After spending much of the ’60s and ’70s at the center of the era’s decadent “sex, drugs, and rock and roll” zeitgeist as a member of The Byrds and Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young, Crosby nearly lost his life in the early ’80s due to dire health problems caused by decades of hard living. (He actually did lose his freedom for nine months in 1982, serving time in a Texas prison on drugs and weapons charges.) After cleaning up, he reunited with Stephen Stills, Graham Nash and occasionally Neil Young, embarking on scores of successful oldies tours over the next 30-some years.

For most artists of his generation, that’s typically where the story ends. But Crosby has had a shockingly productive third act this decade. Starting with 2014’s Croz, his first solo album in 21 years, Crosby has put out a new record almost every year, alternating between his electric Sky Trails band (named after his jazzy 2017 album) and acoustic Lighthouse band (named after his stripped-down 2016 release). During this period, Crosby has made his best music since 1977’s CSN, essentially picking up where that album’s wised-up, jazz-leaning soft-rock sound left off. Offstage, however, Crosby’s life has hardly been mellow — his disparaging 2014 comments about Young’s new girlfriend (and current wife) Daryl Hannah created a rupture in CSNY that caused Nash to declare the band finished two years later.

Crosby doesn’t seem to mind, though; he claims that he quit CSNY anyway. For the new Here If You Listen, due out on Friday, Crosby insisted on billing the album as a collaborative effort with the Lighthouse band, which includes bassist/guitarist Michael League and singers Michelle Willis and Becca Stevens. (The Sky Trails band is anchored by Crosby’s son, James Raymond, a fine songwriter in his own right who contributed a stunning Steely Dan-circa-Ajasoundalike to the 2017 album.) The result is a spare, mystical, and frequently beautiful record that dwells on mortality (the contemplative “Your Own Ride”), politics (“Other Half Rule,” which calls for women to topple the patriarchy), and the past (a new arrangement of Joni Mitchell’s “Woodstock”).

While Crosby is the midst of a creative renaissance, he’s arguably been more celebrated lately for his daily missives on Twitter, an ideal outlet for his candid, funny, and charmingly cantankerous nature. This also makes him an excellent interview — Crosby remains sharp, engaged, and unafraid of revealing too much of himself. During our wide-ranging chat, Crosby was refreshingly frank about his life, his creative process, #MeToo, and why Neil Young is the only person who can revive CSNY.

Why do you think so many of your peers are retiring? And why have you chosen to do the opposite of retire?

Well, they must feel that they’ve done what they want to do, and they need to take a rest. Way I look at it is this, man: I have a limited amount of time. I’m not complaining, everybody has a limited amount of time, but I have a really limited amount of time. And what I ask myself is, what am I going to do with that time? Am I going to sit on my butt and watch TV, or am I going to do the only thing I can do that really makes any contribution? The only way I can help, the only way I can live, the only thing I can do that makes it better, is sing. That’s all I got. So, I’m gonna do it. I’m gonna make music as best as I possibly can, as fast as I possibly can, until the winds come up. Because I think it’s what I’m supposed to do.

You’re obviously very energized at the moment. But has there ever been a time in your life when you contemplated walking away from music?

Yeah, when I was a junkie, before I went to prison. I didn’t think I was gonna live to do any more music. I thought I was gonna die, and die soon. And I would have, if I hadn’t gone to prison. That cleaned me up, and forced me to take another look at my life, and here we are 40 years later.

How hard is it to tour at 77?

I don’t know if hard really describes it. It’s been brutal. Here’s the deal: I was in a big group, and when I quit that group, that cut my income in half. Maybe a little more than in half. And then streaming has taken away another half of my income. So I’m making about a quarter as much as I used to, so I need to tour to live.

The three hours that I’m onstage is heaven. I love being in a band, I love singing. It’s ecstasy to me. The other 21 hours are kind of a bitch. Because we never get more than three hours sleep in a row, and we eat bad food at bad places constantly. I can’t really sleep on the bus anymore — used to when I was a kid, but it’s harder now. And I don’t have the kind of stamina I used to have. So, yeah, it kind of beats you up. But all the same, when you’re doing the three hours that are good, they’re so good that you’re willing to put up with the rest of it.

I read an interview that you did recently, and there’s a quote that I wanted you to elaborate on: “We were wrong — having women in bands is a great idea.”

It absolutely is.

You have women in both of your bands now. Do you feel that there would have been a negative stigma had you done that in the ’60s and ’70s?

Yeah, there used to be a joke about it: You don’t have a girl in the band, because the bass player falls in love with her. You know, that kind of thing.

Right.

It’s nonsense. Girls are just the same as guys, and some of them are drastically freaking talented.

What caused you to have a change of heart?

Oh, little things like Joni Mitchell and Bonnie Raitt.

Just seeing how great they were?

Yeah, if you see a girl that good, then you realize how good girls are, and it changes you.

On the new record, there’s a song called “Other Half Rule,” in which you wish that women would take over the world. Was that inspired by #MeToo?

It is. That’s what it’s about. It’s about saying, please step forward and take a leading role in running this country, because we think you should. We believe in you, we want you to do it. That simple.

How did you feel while watching the Kavanaugh hearings?

Disgusted. Angry. The dirtiest kind of politics being played out right in front of you.

Are you generally optimistic or pessimistic right now about just the state of the world?

It’s very tough right now, man. You gotta remember I’m a guy who went through the civil rights marches, and all the anti-war stuff. I’ve been doing this a long time and been up against some really awful sh*t. I was there when they killed both Kennedys and Martin Luther King, and I felt pretty f*cking discouraged then, I can tell you. But this… our democracy’s in danger, don’t kid yourself. We got a guy who doesn’t believe in democracy, who’s the president. He has the power to wreck a lot of stuff. He’s wrecking it as fast as he can. But to me, he’s kind of an inept f*ck, because he’s not very smart, but he’s doing a huge amount of damage.

You’ve always sought out group collaborations in your career. Even your first solo album If I Could Only Remember My Name, has a lengthy supporting cast.

That’s how it goes with me, yes.

Why have you always sought that out?

Well, it’s like this: There’s two kinds of effort. There’s collaborative effort, and competitive effort. And competitive effort, if you follow it out, all the permutations, out into the future, competitive effort winds up at war. Contributive effort winds up at a symphony orchestra. So there’s just really no question at all, to me. Most of the really good stuff the human race has done, has been done by people doing contributive effort with each other. And so that’s definitely where I lie.

But the bands you’ve been in were also competitive, right? It seems like CSNY was competitive, and maybe even The Byrds?

Oh, within the band, immensely competitive. CSN was, and CSNY was even more a fully competitive deal. Not a collaborative effort at all. But the ones that I’m in right now are cooperative. Very cooperative.

How do you keep a cooperative band from becoming a competitive band?

There’s a lot of forces at work there. First of all, there are the egos of the players. We all have egos [in CSNY], that’s one of the reasons we went onstage in the first place. So that causes friction between us, because we’re all egotistical guys, and we want to be important, and we want to be loved, and we want to be seen, and we want to be the center of attention. That’s just how it is. That’s the kind of people we are. What happens is, you start out really liking each other, and really loving each other’s music. And we did good work out of that. But 40 years later, when it devolves to just turn on the smoke machine and play your hits? Uh-uh, no. That would’ve killed music for me, if I kept doing it.

This has to be the most prolific time of your life. You’ve put out more solo records in the past four years then you had in the previous 43 years.

Yeah, no question. Four albums in four years? It’s not only the best I’ve ever done, I haven’t seen anybody else do it, either.

You’re working on another record right now, right?

Yes, I am.

Can you talk about that at all?

The next one will be a Sky Trails record, and I’m already writing it with James. I have a song that I wrote with Mai Leisz and Greg Leisz. I have a song that I’m working on by myself. I have another song that I’m working on with Becca. I have another song that I’m working on with Bill Lawrence, who’s an incredible musician. And I’m thinking about recording one of Jason Isbell’s songs, because that guy’s a good writer.

Which song?

“Vampires.”

How did you and Jason meet?

Pretty simple thing. I heard that he was doing “Ohio.” Somebody played me a Youtube thing, and it was just very sincere and very straightforward, and I liked it. He’s on Twitter, so I messaged him. I said, ‘Hey, good on you for doing “Ohio,” it’s the song we should be singing right now, unless we can write a better one.’ And he said, ‘Hey, I’d love you to sing it with me.’ And I said, ‘I’d love to, what time’s the bus leave?’ And he said, ‘No, I’m serious. I’m gonna do Newport Folk Festival, would you come sing with me? I’ll buy your ticket.’ And I said, ‘Sure.’ I liked the guy. He said, ‘Let’s do “Wooden Ships” and “Ohio,”‘ and I said, ‘Joy. Absolutely fine.’ So we went there, and he’s a great guy, with a great band, and a great wife, and he’s writing really good music. So, we hit it off. Frankly, he’s one of the people that may drag country music kicking and screaming into this century. He’s terrific. Read “Elephant, read “Vampires,” he’s got a bunch of songs that are good.

I heard you might write a song together?

I’ve got a set of words for him, yeah. That’d be for this next record, too.

Getting back to your recent prolificacy — do you work on music every day?

Yes, I work on it every day.

What’s your process? Do you get out of bed and grab a guitar?

No, I get up in the morning and help cook breakfast, and feed the dogs, and do all the ordinary stuff. Anytime during the day, if I think of three words in a row that I like, I write them down. That comes from Joni Mitchell. One day when she was my old lady, she said, ‘Write that down.’ I said, ‘What?’ She said, ‘What you just said.’ I said, ‘What’d I say?’ She said, ‘What you said was good, David, and you don’t remember it, ’cause it’s already gone, and you do that a lot. You think of stuff that I really like, and then you don’t remember it, because you didn’t write it down. If you don’t write it down, it didn’t happen!’ So I went, ‘Holy sh*t. Okay.’ Because it’s absolutely true, and it was a great gift she gave me, by teaching me that.

So that’s how the words thing goes. The music, every night, man, the routine here at the farm is, we have dinner together, and then I go and build a fire, and then I vaporize a couple of flowers, and get high as a kite. Then I sit down with about five different guitars in the bedroom, in different tunings. I pick out one of them, and start fooling around and see what I find. And I do that every night of my life. Every night.

Have you always done that?

Yeah, I have always done it. I’ve done it since 1961.

I’m just curious about what’s changed for you recently. Because you weren’t a prolific songwriter for many years.

Well, that has to do with two things. One, I had a bit of a head of steam built up from, you know, Crosby, Stills, and Nash not being a successful place for me to take music to. It had gotten to the point where I didn’t feel welcome there, to take a song to. The other thing, and the much more important factor, is the people that I have been lucky enough to write with. My son James is a great writer. If anything, he might be better than me. And Mike League is a great writer. We wrote three of the best songs on that Lighthouse record in the first three days we sat down together. It’s as if you were a painter, and the other person was a painter, and you had different colors on your palettes. Instead of seven colors, you got 14 colors. It’s a better painting.

Apologies if you’re sick of hearing this question, but have you had any recent contact with the other CSNY guys?

No.

Do you expect to ever to play with them again?

You know, it’s been so virulent and unpleasant, with Nash in particular. I would do it if Neil called and said he wanted to do it. I wouldn’t do Crosby, Stills, and Nash, but I would do Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young, if he wanted to. But I don’t think he does, man. Why would he? He doesn’t need to. He’s doing just fine. And I’m doing just fine. I’m not making any money, but I’m doing what I think I should be doing, which is making the best music I can make as fast as I can do it.

I want to circle back to something you said earlier: You said making music is the only way you can help. How does making music help?

I look at this way, man: Music is a lifting force. The same way that war is a downward force, that drags us downward, brings out the worst in the human race. Music is a lifting force. It makes things better. And it’s what I do. And right now, we need that. We need that really badly. Truthfully, we need a marching song, too. We need an “Ohio,” or a “We Shall Overcome.” We don’t have that. We’ll have to use “Ohio” for the time being. But we need the lift that music can give us.

Do you think you’ll ever try to write a new marching song?

I’ve been trying. I am trying right now.

Here If You Listen is out on October 26 on BMG. Get it here.