Luke Bonner felt restless upon moving back to his hometown of Concord, N.H. eight years ago. From 2009-12, Bonner played overseas for clubs in Hungary and Lithuania and had a cup of coffee with the Austin Toros, the Spurs’ G League team. He was a self-proclaimed nomad every summer, splitting his time between Austin, Boston, and Concord. Bonner grew up the youngest of three siblings in a basketball-inclined family — his brother, Matt, is a two-time NBA champion; his sister, Becky, played overseas before becoming the Director of Player Development for the Magic — and had an intuitive understanding of the disruptive beat careers in the sport can have on the rhythm of a regular life.

Concord, settled in what once was the watershed of the Merrimack River that winds through the city, is hugged by gently climbing hills that roll into woods daisy-chained with lakes, downtown still a snapshot of the Neoclassical and Federal-style architecture of the 1800s with its grecian columned and gold-domed State House and downtown stretches of tall, shoulder-to-shoulder snug redbrick buildings. One time, Bonner recalls, Kwame Brown and Brian Scalabrine came to visit when Summer League was held in Boston and only had one person politely approach them with the advice that they might want to try basketball some day. It’s the sort of place, Bonner says, “where if you were super famous, everyone would just be like, ‘Hey, that guy looks like Brad Pitt.’ You would never be like, ‘Oh, that’s Brad Pitt.’” The sort of place where Bonner could let the rhythm of his life settle, at least a little.

Two summers ago, when Matt was back in Concord to run the annual Bonner Basketball Camp, he and Luke struck up a conversation with a local developer who was fixing up some of the older buildings around town. The developer, Mark Ciborowski, owned one particular historic building that piqued the Bonners’ interest.

“I have these vague memories of when I was little, really little, of there being a random gym, meathead fitness club thing, right downtown,” Bonner recalls of the space where his dad once taught aerobics and his mom would sign people up for classes. The brothers’ minds instinctively went to one thing.

“We asked him, ‘Hey, is there a court in that building?’” Bonner says. Ciborowski confirmed and took them into the building’s abandoned upper, open floors to see. Bonner’s voice still lifts in quiet awe when he remembers what they saw, a court tinged with a fair amount of dust and debris, light spilling onto it from floor to ceiling windows, “We were just like, ‘Are you kidding me?’”

The space would sit vacant for a little longer. Bonner occasionally used it to host one-off events for the work he did with his ad agency, like welcoming candidates during the last presidential election to come shoot hoops when they were in town. But it stirred up something in him. It seemed like the place where the fervent, occasionally restless passions that had driven him since he stepped off the court could come together.

—

Long before individuals who participate in college sports became able to profit off of their name, image, and likeness earlier this year, Bonner championed the rights of college athletes.

“I grew up in very unique circumstances. I’m five years younger than Matt and four years younger than Becky. They were both All-American players,” Bonner says. “But [I] also saw what the experience was like for my parents and how stressful it was. Even though my brother and sister were both full scholarship, top-tier college basketball players, there’s a lot of things that stood out to me even when [I was] in middle school thinking, ‘Oh, wow, this is really cool, there’s 20,000 people chanting my brother’s name on this game on CBS on a Saturday afternoon.’”

Bonner pauses a beat, “And then you think about it and you’re like, ‘Wait, there’s 20,000 people at this game chanting my brother’s name on CBS in the afternoon [and] my parents can’t even afford to go see him play.’”

In 2014, Bonner co-founded the College Athletes Players Association (CAPA) alongside a pair of college football players, Ramogi Huma and Kain Colter, with the intention to unionize the Northwestern football team. They had the additional support of United Steelworkers and were initially successful, but the ruling was overturned by the National Labor Relations Board in 2015. While various reforms to college athletics have since been brought forward, including the College Athlete Right to Organize Act tabled by U.S. Senators Bernie Sanders and Chris Murphy, there are many former athletes, like Bonner, who consider the more public-facing amendments like the NIL rule “easy and obvious.”

“Every incremental positive for players at the collegiate level of the United States has been the result of, basically, a lawsuit,” Bonner says. “A lot of the rhetoric from the NCAA side, or the administrative side, is that it’s only going to help the top one percent of college athletes. And I find that really offensive and it almost fires me up a little bit.

“By saying that it’s only gonna help the top one, you’re basically saying the other 99 percent of your athletes in college sports have zero value as human beings, ‘cause NIL isn’t just influencer posts and paid posts and stuff like that. It’s everything you do,” Bonner gives the example of his brother’s basketball camp, or an athlete appearing on a podcast. “The default stance from NCAA is always, there’s only interest because you’re an NCAA athlete, which is bullshit.”

The legal system moves slow. Against behemoths like post-secondary institutions and the college athletics system the schools are entrenched in, that pace can be glacial. Bonner knew there was more he wanted to be doing, but the vehicle in which to do it didn’t pull up on him until he began fiddling with its eventual engine.

Bonner had been working with an athlete on a personal project and started to look at the search analytics their name returned on a monthly basis, finding the numbers to be “really high.” At the same time, Bonner had been watching the endorsement space and, when he realized the athlete was delivering high search returns despite no personal website or e-commerce in place, he went to his friend and former coworker in the agency space, Allen Finn.

“And I just kind of said something like, ‘Somebody should build a thing where it’s really easy to stand up the shop, sell stuff that’s meaningful, and that can be an easy digital hub for an athlete,’” Bonner recalls, noting that it didn’t need to be a “full on personal site” but a one-stop spot outside of a team contract. “Basically like Etsy for athletes.”

As is often the case when an idea stubbornly settles, Bonner and Finn realized that they should be those somebodies. Bonner was already fired up with how far he felt changes like the NIL rule fell short, and Finn, who is in Bonner’s words, “one of those people where they’ll figure anything out,” pushed his friend past talking around the idea of something that could quickly be a difference-maker in the lives of athletes at the college and professional level.

Bonner began to share the idea for the new project, called PWRFWD, with agents he knew through the wide-ranging network of the Bonner siblings both as a way to put the feelers out and to “make sure I wasn’t crazy.” The response was overwhelmingly positive, something Bonner attributes to being honest and transparent with what he and Finn wanted to build, which helped them establish a sense of trust early on for the four people who would join them from the beginning as founding athletes: Sue Bird, Mo Bamba, Breanna Stewart, and Tacko Fall.

“What appealed to me most about PWRFWD, and working with Luke, was just the fact that the players, the athletes, were put first,” Stewart says over the phone. “I feel a lot of times for athletes to have logos on a shirt, or names on a shirt, it seems always really, really difficult. And Luke was just like, this is what we’re going to do. And whatever design we want, we’ll come up with the concept, and we’ll get your gear out there so people can represent you.”

“PWRFWD allows me to build out my brand in a way that I can retain ownership and control over the messaging, creative, and product types. I think there’s a substantial opportunity for us to provide value to athletes and fans that are too often underserved or overlooked,” Bamba echoes.

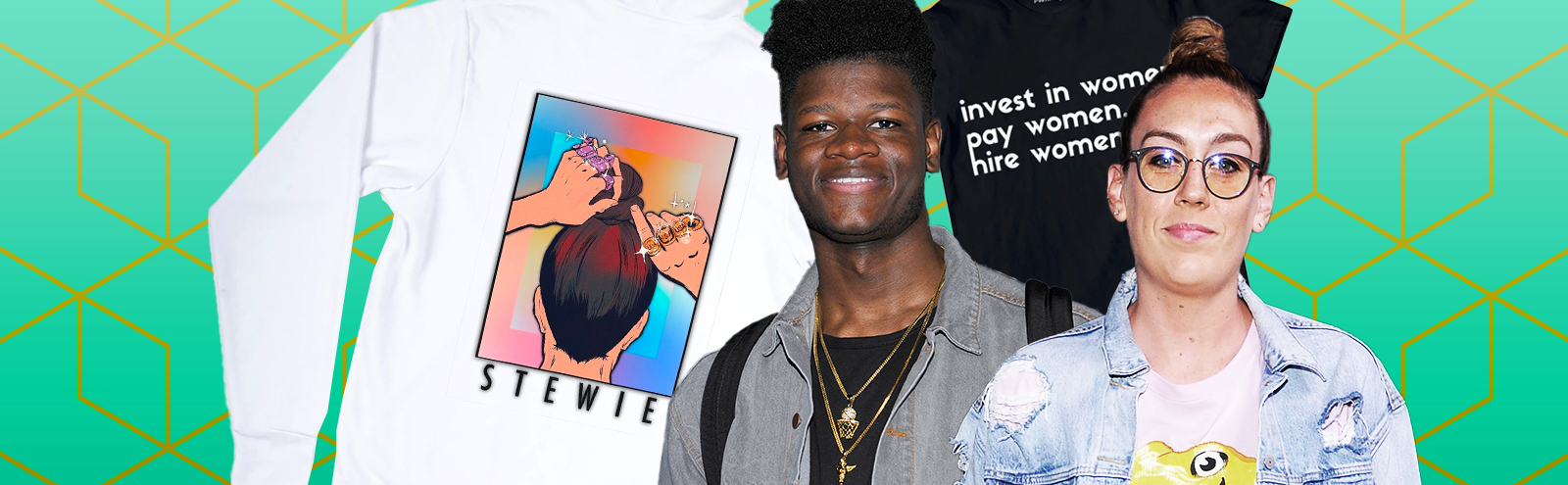

Though Bonner originally envisioned focusing on basketball for the first year, PWRFWD now hosts 68 athletes across basketball, football, baseball, soccer, tennis, MMA, swimming, as well as media. Kelsey Trainor, for instance, has a popular ‘Invest in women. Pay women. Hire women.’ shirt and hoodie.

With so many different athletes signing up for the kind of commercial and creative space Bonner was offering, he and the PWRFWD team, now made up of 10 full-time employees scattered from Concord to San Francisco and interns at various colleges throughout the year, realized quickly that the creative process had to be hands-on for everyone to reflect the myriad backgrounds, sports, and interests each person brought to the table. And that process extends to the physical items each athlete wants to offer, the design process, and the quality of the final product which utilizes only on-demand production practices to decrease overall waste.

“One of our responsibilities is ensuring that we’re creating something with the athlete that is true to what they want, whatever that is,” Bonner says. “Athletes will do this for different reasons. It might be to make a statement. It might be to support a cause that’s near and dear to them. It might be for fun and for vanity. So understanding that is kind of key.”

That creative process starts as soon as an athlete decides they want to join PWRFWD in a kickoff call with Bonner and the design team. It’s an intriguing spectrum where some people come with a full aesthetic in mind or designs in hand, while others may only allude to glimmers of personal interest that Bonner and his team have become experts at panning for creative gold.

“It almost always emerges organically, somehow,” Bonner says, mentioning the initial call his team had with WNBA player, Sylvia Fowles, whose lockdown obsession with houseplants gave way to her Plant Parenthood line of merch, with hoodies and t-shirts showing tropical houseplants nestled in basketball planters.

Bonner says that those conversations have been some of the most fascinating, and while he almost wishes he could put them into the world, he also acknowledges that when anyone is getting involved on the creative side, “you are vulnerable at the same time. And being able to make people feel comfortable, and to be honest about what they’re trying to accomplish. It’s a really cool experience, personally, for me to have.”

One of the first faces on the PWRFWD team that new athletes get to know is Hannah Nelson, the company’s first Athlete Success Coordinator. Nelson, who grew up outside of Concord, played basketball throughout college and knew Luke and Matt through the Bonner Basketball Camp. She had been a supporter of PWRFWD since it started, oftentimes directing people on social where to buy merchandise or talking up the company in her networks.

“And I guess they noticed that,” Nelson laughs.

Bonner contacted her and asked if she’d be interested in joining the new team as an intern, but Nelson quickly found herself doing “a little bit of everything,” from administrative organization, to number crunching, to the hands-on creative process with athletes. It was that process that appealed to her most because it was apparent each piece of merchandise had come from the mind of the athlete, there was no sign of the too often ubiquitous last name and number. Now, in her full-time role, Nelson values helping athletes “figure out who they are, what kind of merchandise they would like, that’s personal to them” all with the end goal of letting people know they’re more than just an athlete.

“We definitely collaborate as a team,” Stewart says, giving a soft chuckle, “Funny, I just got off a Zoom meeting with the team, and just talked about what we liked from the last line.”

For Stewart, her first release was a series based on a photo she’d taken on her phone of all her rings lined up, that the PWRFWD designers turned into a punchy, effervescent graphic of Stewart from behind, tying up her hair for a game with a ring on each finger. These shirts, along with shirts for Storm teammate Jewell Loyd have popped up around Seattle, which Stewart calls “awesome.”

That sense of ownership is crucial to the company’s, as much as Bonner’s, business model, in that every item listed on the site as a finished product belongs to the athlete, not to PWRFWD.

“I don’t know if consumers or fans necessarily understand that when I buy this Charli Collier t-shirt from PWRFWD, I’m literally buying it from Charli Collier,” Bonner stresses. “And it’s either going to the cause that she wants to give it to, or it’s going to support her to do her thing.”

Athletes who have existing partnerships are encouraged to highlight them and build fulfillment, like the partnership Bamba has with Detroit-based jewelry designer, Rebel Nell.

“We can sell that product on our shop homepage,” Bamba says, “and PWRFWD handles all the backend stuff to get the product in the customer’s hands and get Rebel Nell the cash from the sale.”

It also allows athletes like Bamba to think beyond the traditional avenues of athlete merch, as he already has ideas percolating for future additions to his shop. “Candles! I love a good candle,” Bamba says. “Soon you might even be able to buy one where the wax has my signature haircut that sorta melts over time.”

In this way the PWRFWD model is unique. Athletes aren’t plugged into existing campaigns led by a parent brand, whatever they want to sell is being created by and with them or, if it exists already in a previously established partnership, isn’t restricted but helped to grow. It’s an almost aggressive approach of reclamation when considering that many are, for the first time, exercising that kind of absolute control, especially for athletes who came up through the same exploitive system Bonner did.

“I think that as athletes, we see there’s a lot going on and I would say what we do on the court is important, but not the only thing we do,” Stewart says. “So to be able to have control, to be in those meetings for off the court things, for continuing to help build our brand, is something that’s really exciting just because we’re able to lead the charge and not just be the ones following a big company or something.”

“You see it with the NCAA now, and when I was in college,” Stewart adds. “We didn’t have control over our own likeness and image. And now working with Luke, he makes sure that we do.”

Bamba finds it empowering, being in control over each step, noting how straightforward the actual business transaction part of the process is. “Everything is simple and transparent. I get a report each quarter showing exactly how much I sold and what the margin was on it.”

Bonner acknowledges that creating a business “where the athletes win before the company does, might be stupid short-term,” but thinks it can set them apart long-term as they build that trust with athletes. The importance of a company with an ethos like PWRFWD’s is simple, maybe, in the way that most life-altering inventions often are, but not, stupid. In an era of athlete autonomy and empowerment that has been too often put in air quotes by leagues and organizations like the NCAA virtue signaling with optics and lip-service rather than listening to insight from the athletes driving these businesses, Bonner and PWRFWD have come in like a quiet corps of utilitarian engineers, building a direct bridge from athletes to the people who happen to be their biggest and loyal consumers — their fans.

At a recent practice on the road, Stewart saw a young player wearing her Rings hoodie. “That’s cool because she went out of her way to get that. To see these fans finding ways to represent us, and now Luke has created that with PWRFWD. He has given them a place to get easy access to connect with the athletes, to represent us and to help build women’s basketball up.”

Bonner’s vision for the company’s future is likewise simple and straightforward, to continue doing what they have been with a focus on transparency and trust that’s geared toward growth for an athlete’s brand, platform, and entire person.

“Catering specifically to what is the life of an athlete outside of a team contract and how can we help facilitate income and more engagement, and allow them to own all of that themselves. What I have been drawn to is areas where there’s an underserved fan base and overlooked athletes, is where I think that there’s a lot of power to what we’re doing,” Bonner says, his usual affable tone shifting serious. “I’d love to see, if you go to an athlete’s shop, that doesn’t just mean t-shirt and hoodie anymore. It’s, sign up for camp registration, an experience, so on and so forth.”

PWRFWD’s founding athletes share those same hopes. Stewart says she hopes the company will “continue to be an outlet for people to express themselves as an athlete, as an activist, as an ally, and just in as many ways as possible.” Bamba believes it will become a go-to for athletes at all levels who want to build something with their personal brand that will be unique to them — “Pro athletes. College athletes. Anyone with any following, really.”

Building on the cause has remained keen and close for Bonner. It’s what propelled the idea for PWRFWD in the first place, and there’s the full-circle hope that the company can be a place for college level athletes to reclaim themselves, eventually reflecting the self-actualization players in the next generation will have known all along.

“Part of my theory is that you don’t necessarily know who’s going to be very good at the internet. You don’t necessarily have to be an All-Star to be that. Especially when you think of college sports, there’s a lot of people,” Bonner says. ”And there’s a lot of really interesting, inspirational personalities in that realm who may get overlooked for certain types of deals, but may actually be able to drive a lot of that on their own. College is definitely an area that we’re looking at as that world opens up.”

It took Bonner returning to where he came from, both physically in the world as much as what’s been most important to him, to start PWRFWD, and that those roots weave through everything is clear.

There’s a vision that Bonner has for Concord and the PWRFWD HQ, a place he can invite athletes to come hang and shoot hoops, and it parallels the vision he and his team have for how they can accelerate total autonomy for those same people to exist past the margins of their sports and athletic skills.

“That’s part of the driving force in what we’re doing,” Bonner says. “there’s a lot of athletes that, I think, hold value. And I think we have a tool that we’re building that’s really helpful for everyone, and simultaneously, I think it’s going to have an impact on the landscape, big picture, eventually.”