It’s really easy to dismiss haute cuisine with an epic eye roll and dismissive wank. It can be finicky, stuffy, pretentious, and egocentric. It’s the supermodel aesthetic writ large in the world of food. We all stare longingly at some gelatinized cube of flavor with that innate sense of inadequacy driving us to either sell our cars to be part of the experience or to dismiss it entirely. Even chefs — so charmed by the form and function of food — have a long history of abandoning the fine dining scene for food trucks, always chasing the ultimate cooking buzzword “accessibility.”

Honestly, I love food. If you’ve read anything I write here on the subject, you’ll know that already. But even I rarely find myself geeking out on haute cuisine. One, I’m a poor writer who can ill-afford a $200 tasting menu with a $95 wine pairing — much less when you multiply that by two if my wife is joining. Moreover, I’m a very, very frugal person. I wear almost identical sets of clothes until they’re threadbare. I recycle everything. The idea of spending close to $800 on a single meal — no matter how transcendent — just feels… well… off.

Don’t get me wrong, I get why fine dining prices are expensive and I respect that. The training and quality of the staff (front and back of the house) at a three Michelin starred restaurant is worth every cent they charge. It’s just not really my jam. I’m more the dude that goes to Paris and hangs out in the Lebanese neighborhoods, eating schwarma, and shootin’ the shit about 80s Schwarzenegger movies.

That’s not to say I’m not open to eating at these places. I’m a food writer, after all, and hauté cuisine is a crucial part of the entire food ecosystem. Besides, even if my philosophy differes, I too fall into the habit of lusting over the great enfant-terrible chefs of our age. I follow Rene Redzepi, Vladimir Mukhin, and Alex Atala (amongst others) semi-obsessively. I respect their artistry immensely.

But I never fully realized what magic ingredient it was that drew me to these chefs. At least not until I sat down with two of them to eat a small, four-course tasting menu in Berlin.

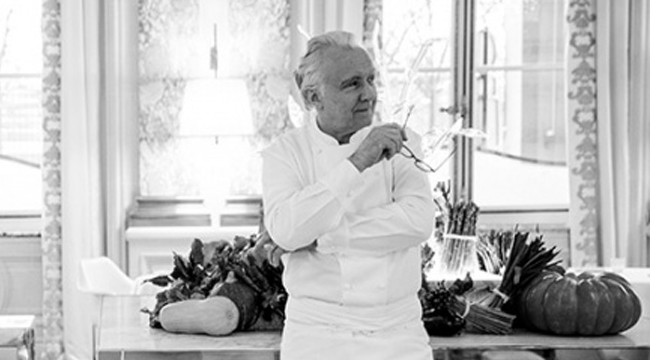

A little background. Alain Ducasse was in town for the Berlinale premiere of his new documentary, La quête d’Alain Ducasse (directed by Gilles de Maistre). The film was being screened for a select few in the belly of the infamous architectural wonder Martin-Gropius-Bau, followed by a dinner with Chef Ducasse by the three-Michelin-star German chef, Thomas Bühner, of La Vie.

It’s okay if the paragraph above makes you roll your eyes. I feel you.

The Culinary Cinema program at the Berlinale has evolved and blossomed over the years. They host about six to eight premieres with dinner pairings and then show all the films one more time on the IMAX screen. If you love food porn, seeing it on an IMAX is surely a climatic experience.

Anyway, I scored a ticket to the Alain Ducasse dinner and rearranged my entire Monday night to assure I could attend. After all, the chef might be the most important person alive when it comes to French cuisine. His restaurant empire is legion. He’s collected 18 Michelin stars over the years (only Joël Robuchon has more at 31 stars).

de Maistre’s film is a frenetic account of a year in the life of Chef Ducasse as he crisscrosses the globe attending to his restaurants, meeting heads of state, and planning and opening his crowning achievement at Palace Versailles. It’s a whirlwind documentary about a man who seems to only sleep in first-class cabins on planes. But, at the end of the day, it’s nothing too different from every other food documentary out there about a star chef.

The only identifiable x-factor is that Chef Ducasse loves food in a way that few of us could ever fathom. Imagine the seriousness Steve Martin has for comedy, magic, and banjo and apply that verve to food, restauranteurs, and fine dining and you have Alain Ducasse. He’s a great artist. He’ll blow you away on stage (or in the kitchen in this case). But, behind that curtain is the most serious person you’ll ever encounter: A perfectionist of the highest order who understands his craft on a zillion different levels.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BfF-ls5BA_N/

Since I was at the Berlinale with a press pass, I was greeted first by the Culinary Cinema’s press rep with plenty of wine to keep me busy while everyone was seated. It was tactic to make sure I was as happy as I could be. It worked. Chef Bühner made a brief appearance to welcome everyone and raise a glass of white (a fantastically subtle saffron-tinged Grauburgunder {German Pinot Gris} from Baden) and start the festivities.

The courses came at a pretty solid pace. First, there was a potato foam with the denseness of a semi-set pudding, paired with a dollop of curried pumpkin ice cream. It was a fascinating dish. I’ve been obsessed with potato foam since a trip to Madrid back in the day when an old chef friend of mine from elBulli taught me to make it. This foam was objectively better and far more exciting. The juxtaposition of the ice cream in the warm foam didn’t make sense on paper but made total sense on my palate. I would never have thought that hot potato foam and ice cold ice cream would work. But here we are. That is the ultimate trick of hauté cuisine. It’s an exploration.

Next came a small tin with Imperial Caviar resting on a bed of smoked salmon mousse, covered in a thin layer of beet gelée. This was, by far, one of the best dishes I’ve ever eaten. Top ten. The salmon mousse was a great throwback to the 70s and 80s when emulsions like that were all the rage. The beet jelly was bright and earthy. There was an eel tartlet on the side — part creamy cheesecake, part delicate, smoky eel. And the caviar was like a drug. The purest dope imaginable. Each egg popped with delight. The cleanness of the roe was highlighted with a hint of brine which was, as Niles Crane once articulated, “like being kissed by a lusty mermaid.”

I’m honestly having a hard time remembering what came next. I’m still caught up — dreaming of those lusty mermaid kisses calling me like a siren, off to Iran where I can spend the rest of my life eating caviar and watching Caspian sunsets.

Okay, okay, sorry. Next, we were served a saffron-forward bouillabaisse consommé with marinated cod, Chūtoro (fatty back belly of the bluefin tuna), and aromatic greens and flowers. It was a crisp and unctuous delight. This is where a realization came over me. I asked myself why I’d never made a consommé before. I’ve made a million broths and stocks and soups. But the crystal clear waters of the consommé never came up. I knew I needed to correct that as soon as I got home.

Then — as I ate celery milk ice cream with Ivory Coast chocolate and dill oil — the heavy realizations all kind of came crashing down. This food is less about the experience of the moment and more about “what happens next?” It’s not a monolith. It’s a foundation awaiting all of us to build upon it. Haute cuisine is a glimpse into endless possibilities. It’s an exploration of human creativity. It’s a once in a blue moon moment. A glimmer of what food can offer, far beyond sustenance.

I’d spent my life looking at haute cuisine as something that was the end of the road … a destination for any chef. It’s not. It’s a beginning that asks you whether you’re ready. It piques your mind. It sparks curiosity. It was inspiration as nourishment. It was watching Steve Martin change the game for stand up in a packed, sweaty arena and then going home and starting to write your own tight five that very night.

I felt the same watching Chef Ducasse and Chef Bühner eating, talking, and experiencing food. It was more than just a dinner or meal. It was the beginning of a journey. Every meal is; even if you’re just microwaving a frozen burrito.

I went home that night, dizzy with ideas (and wine). I was ready to start working on my tight five. So, I put a smoky sweet and sour pork shank in my sous vide bath and waited for 24 hours. The next day, I removed the shanks and wrapped them up to settle. Then I gently whipped some egg whites until they were just starting to froth and whisked them into the all the marrowy, smokey, sweet and sour jus from the sous vide bag.

I brought that to the lowest of simmers until an egg white raft formed and drew all the impurities from the jus, leaving behind a clear consommé that was packed with glorious hints of smokey brown sugar, apple cider vinegar, winter spices, and deeply lush bone marrow.

That was it: I had finally made a consommé. A good one, too.

The Ducasse dinner had pushed me to challenge myself and my craft. In the process, a whole new world opened up. Not a destination, just a whole bunch of new (fun) roads to travel. I realized eating with Chef Ducasse that this is what haute cuisine is: a call to culinary adventure. And I’m glad that I finally heard it.