In May, The 1975 released “Give Yourself A Try,” the first single from the band’s forthcoming third album, A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships, which finally comes out Friday. Within the space of 197 seconds, the sometimes cocky, sometimes earnest Manchester quartet manages to show off everything it does well. “Give Yourself A Try” is extremely polished and unrepentantly trashy, a firecracker spitting buzzsaw guitars and jittery 808s, all in service of a point of view that’s specific and yet also scans as a generational statement. Like all great 1975 songs, it’s a big tune that feels intimate, a fun trifle that’s somehow freighted with meaning.

A few months later, the 1975 doubled down on all of those very 1975 signifiers for the album’s next single, “Love It If We Made It,” a rambling electro-pop confection that references Donald Trump, police shootings, Lil Peep, rampant consumerism, lead singer Matty Healy’s heroin addiction, Jesus Christ, Kanye West, and several other memes, like a nervous breakdown unfolding on Instagram. It’s probably the band’s best track to date, and arguably the song of 2018.

From the beginning of the 1975’s career — which launched in 2012 with the early British chart success of grabby hits like “The City,” “Sex” and “Chocolate,” that set the stage for the band’s self-titled full-length debut the following year — they have been a wonderful singles act. They’ve also been a somewhat less wonderful albums band. A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships surrounds those indelible early teasers — which also include “TooTimeTooTimeTooTime,” “Sincerity Is Scary,” and “It’s Not Living (If It’s Not With You)” — with scores of stylistic diversions that, for better or worse, point to where the band’s true soul resides.

At their most palatable, The 1975 specialize in the sort of ’80s revival anthems that will be remembered as the default sound of hip 2010s indie pop music. (The 1975 is part of the 1989 generation.) But on their albums, they deliberately reach beyond their grasp — A Brief Inquiry includes homages to Soundcloud rap, lounge-y jazz, wispy singer-songwriter confessionals, UK garage, Eno-esque ambient soundscapes, and (most thrillingly) Oasis’ “Champagne Supernova.” Like 2016’s similarly diverse I like when you sleep, for you are so beautiful yet so unaware of it, A Brief Inquiry is easy to admire as a gesture of bold artistic grandiosity and sometimes difficult to slog through as an album. The peaks are high and the valleys are lumpy and willfully trying. (The jazzy cut, “Mine,” sounds like bad Norah Jones.) But through it all, A Brief Inquiry confirmed for me a simple truth.

This is a rock band.

“Is The 1975 a rock band?” has been a recurring narrative in the conversation about this band from practically the beginning, and it remains very much a Rorschach test for how different constituencies view them. A 2016 Rolling Stone profile referred to them as “one of rock’s biggest new bands,” while a recent episode of the New York Times‘ music podcast Popcast suggested that The 1975 is too musically diverse to be credibly classified as rock.

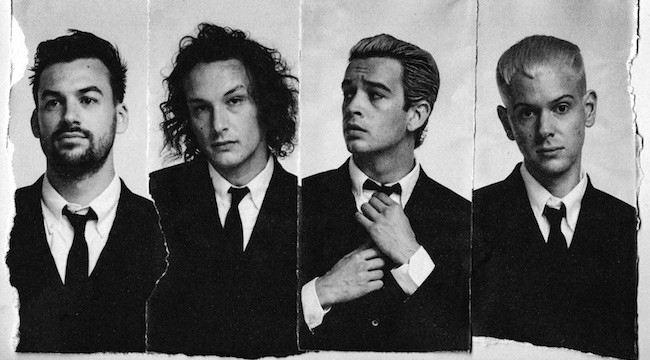

As for the band members themselves, they’ve sent mixed messages on this issue. They certainly look like a rock band. If Jim Morrison crawled out of his grave tomorrow and immediately sought out new music, he would be heartened to see Healy, the rare modern frontman who feels secure enough to wear leather pants while also going shirtless. A 2016 Spin profile played up the 1975’s roots as an erstwhile emo band that ultimately won over fans by touring rigorously.

“Do people want to come see you? I think if you want to see how big your band is, book a show,” Healy said, echoing a bedrock tenet of rock ideology. In that Rolling Stone article from the same period, Healy blasts pop stars generally as shallow and uninspired, and appears to subtweet pre-fab groups like One Direction, an early champion of The 1975. “We resent a lot of people because we f*cking care about what we do. And people don’t care about what they do. If they did, they wouldn’t be in a sh*tty band that’s put together by somebody. They wouldn’t be molded. I worry people don’t like my band. But at least I stand for something.”

As The 1975 caught on in England — and, more slowly, here in the US — back in the early ’10s, they were often classified as a boy band, a distinction that rankled Healy enough to point to the ambitious I like when you sleep as proof that “we can’t be regarded as a boy band anymore,” as he told Spin. But more recently, The 1975 have seemed quite comfortable wearing their affinity for pop on their sleeves, covering Ariana Grande’s “Thank U, Next” and publicly canoodling with Grande on Twitter. This is not something that, say, Greta Van Fleet would ever do.

All artists resist being put in a box, and The 1975 have ultimately made genre-defying restlessness their brand. “The critics were very confused about us around the first record,” drummer George Daniel explained in that Spin interview. “And they accused us of being confused sometimes… like, ‘This band doesn’t know what they want to be.’ We do, we just want to be different things, because that’s a generational way of creating music… that’s the way that we consume it, so that’s also the way that we like to create it.”

Again, The 1975 have found a way to make being themselves appear to be an era-defining act. Though this is less about one band supposedly representing the omnivorous tastes of an online generation than how rock music itself has come to be defined so narrowly that it means practically nothing. For all of the factual issues plaguing the recent Queen biopic Bohemian Rhapsody, one thing it conveys accurately is that at least one rock band more than 40 years ago was experimenting with pop, dance, R&B, country, and classical music within the framework of rock. Albums like A Night At The Opera or Jazz are at least as radical as anything by The 1975, and yet nobody questions Queen’s rock cred.

Especially in the history of British music, examples abound of bands that are broadly considered rock who routinely ventured far outside of rock: The Clash dabbled in hip-hop and reggae, the Jam fell hard for ’60s soul, New Order evolved from post-punk to full-on dance pop, Depeche Mode started as a straight-ahead synth outfit and became an arena rock band, The Stone Roses and Primal Scream melded trad-rock with ’80s rave culture, and Pulp and Blur were similarly malleable with rock, pop, and electronic music in the ’90s.

If The 1975 wouldn’t have been unusual then, why do they seem unusual now? What’s changed in the past decade isn’t the adventurousness of musicians or the open-mindedness of music fans. It’s the agendas and preferences of gatekeepers. “Rock” once was a catch-all term for all forms of popular music; the whole point was to be diverse, at least musically if not always culturally. But now — with the exception of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, which was established in the mid-’80s, back in rock’s ecumenical prime — “rock” is widely presumed to be the opposite of inclusive, and is defined in such a way to ensure that it is so. On rock radio and streaming services, “rock” tends to be restricted to aging legacy acts like Muse and the Foo Fighters, or the dregs of mainstream metal, such as Five Finger Death Punch and Disturbed. Meanwhile, indie music — which used to be called indie rock — has been shunted over to a separate category.

In a way, The 1975 played a pivotal role in the break between rock and indie music. In the fall of 2013, the 1975’s self-titled debut was part of a bumper crop of landmark albums — which also included debuts by Lorde, Haim, and Chvrches — that decisively re-centered so-called underground music away from distorted guitars and aggressive rhythm sections, and toward music that embraced the glossy pop that indie music had rebelled against in previous generations.

Ideally, rock music might once again be defined a little more broadly, to account for the many different kinds of music and people that have influenced the genre. Though, ultimately, when it comes to a band like The 1975, perhaps genre distinctions don’t really matter all that much anyway. The 1975 is a rock band if you need them to be. And they’re also not, if you rather they weren’t. But as long as “rock” still exists as a semi-useful genre tag, it should be applied — along with many other genre tags — to The 1975.

A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships is out 11/30 via Dirty Hit/Polydor/Interscope. Get it here.