When I called legendary broadcaster, Doc Emrick to talk about Topps giving him a baseball card, I thought I had the wrong number. The first voice I heard was distant, and seemed to be a woman asking questions. An afternoon Detroit Tigers game is on the radio, not the announcer I was expecting to hear from. And then Doc finally reassures me that I have called the right phone.

“Just a second, sorry,” Emrick says, and I politely and patiently wait for a transaction to finish before we get started.

“I apologize,” he said, laughing. “I got caught in the drive-thru line trying to get a Diet Coke.”

Even if I were upset about the delay, Emrick is as nice as ever about it all. He appreciates me calling, he said, and started asking questions about my area code (716, Buffalo and much of Western New York) and where I’m from. We talk about where I live now, Boston, and how he had a conversation about real estate there once with Bruins defenseman Zdeno Chara. Soon we were talking about apartment prices, and his three favorite cities to visit (Boston, Chicago, Pittsburgh) while working. We also mourned the loss of a beloved Boston sports bar, which closed this month due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“What an awful thing,” he said. “The Bruins get knocked out on the very day they close The Fours. What a curse.”

The half hour that follows is as much an interview as it is a warm conversation between two strangers, one asking questions and the other eager to tell stories and entertain. We were both trying to do our jobs, of course, but its as refreshing a conversation as I’ve had in 2020.

Emrick is as nice as one would imagine, excited about his job, and thankful to NBC for letting him do it from home. He’s also thrilled Topps put him in their Allen and Ginter set, and later he texted me photos of some cards from his collection and another that was made of him. It’s been a rough year for everyone, including NBC Sports’ lead hockey broadcaster. But a conversation with him, I found, will do its best to help make it better.

Uproxx: What has this process been like for you? Remote broadcast has certainly happened before for the Olympics or things like that, but this is the postseason and now you have to do it. What’s it been like for you?

Doc Emrick: It was actually a challenge at first and now it’s gotten to be fun because you realize that the adjustment that you and your partners had to make… there’s one game that Eddie (Olczyk) and I did, the first game, he was in Stamford, I was here and Pierre was in Edmonton. And later on he was back in Chicago because he had to go back there for a few days to repack to go inside the bubble in Edmonton. So I was here, he was in Chicago, and Brian Boucher was in Toronto. So it’s a little bit helter skelter, but remarkably, through technology I don’t understand, it works. And we get on our headsets and practice counting back and forth to determine what the lag is and it’s remarkable how small it is. It’s well under half a second and it’s only a handful of frames. I think it’s 24 frames a second. And it’s well below, a fraction of as second, in terms of the distance we have to cover.

It’s really a wonderful thing that’s enabled us to do play-by-play of sporting events with virtually no delay.

And it sounds and looks and feels the way people are used to with a hockey broadcast. I was wondering if after the first few games you went back and maybe watched the broadcasts you did to see how they compared to what you’re used to producing to see the result?

No, I let them appraise it at the head end and tell me, because it seemed like a normal broadcast. The start of the game as I was seeing it on my monitor and describing it seemed like a normal game that I was seeing it with the naked eye.

The same limitations that I was having in the arena were the same ones I would be having on the screen: which is that the far winger oftentimes is not turned where you can read his sleeve number. If you imagine a right hand shot will be turned and facing you, but if he’s a left hand shot his sleeve will be turned away and his back will, too. So now you have no identification unless he skates a certain way, which you can pick up. Or unless he’s a (David) Pastrnak who has hair coming out from underneath his helmet. Bad example, because Pastrnak is a right-hand shot, but you see the point is that sometimes you do have to wait a little bit longer to identify a player on the far wing.

That is exactly the same problem that you would have in the arena in that even with the naked eye we are usually so far back inside these press boxes that you’d have to wait a split-second longer to pick up a winger. Because you don’t see his back number, which is very large, and his sleeve number is four inches. And so to make the proper identification you don’t want to guess because your educated guess is probably not right. Your best bet is to wait a split second longer. And you don’t like to do that, but it’s the nature of the business.

As Patrick Roy once said when he gave up seven goals, ‘I’m paid to get those.’ And that’s what our job is.

But it’s fun, and I’m honored that NBC has gone to this extreme measure to allow me to do the Conference Final and the Stanley Cup Playoffs. Because it’s the most fun to get to be there when they present the Stanley Cup. And to chronicle the sacrifice that these guys go through to get there and how much punishment these guys go through to get their name on it.

How long have you been around Boston?

I’ve been here about two years now.

OK, there was a player for the Bruins when they won in 2011 named Dennis Seidenberg, who actually stayed around Boston a bit then played for the Islanders. I remember asking him a few year after they won the championship ‘How many times have you worn your ring?’ And he held up one finger. They are so gaudy that they don’t wear them very often. And they get their name on the trophy and they get to see it when it’s brought out for the celebration for the banner raising. But they don’t get it for more than one day to have a celebration with family. And their name is not on it at that point, the engraving takes place over the summer. So if they see their name on it, they see it at the banner raising in the fall and then the trophy goes back to the NHL and winds out going on tour 300 days.

So they battle hard to get their name on a trophy they can’t keep and a ring that’s too big to wear, but you never see them battle harder than when they go into this.

There’s a grind in covering the postseason and a routine in being at the arena to experience it. Are you trying to replicate that in some ways to get ready to broadcast from home?

2020 is odd for all of us and not because I’m at home but because the joy of covering a playoff is being close to players and after the pack peels away, going and sitting down next to a player in a dressing stall and asking a question about something you’ve been curious about and all of a sudden you get a story that you wouldn’t have gotten otherwise about a player’s background that you can use in your telecast. And there’s no chance of that this year because we have no access to dressing rooms. Any interviews you get with players are all public, which I get with the rest of the media.

There’s hardly any camaraderie with the rest of the reporters you would be with anyway because very few, there’s only one reporter permitted per media source. And so all of the camaraderie you’d have with the print guys and all the other electronic media guys you would normally see. That’s different. The time you get with coaches is limited compared to what it’s been. And that’s not to say it’s wrong, it’s just necessary. And that’s different too.

So what I’m saying is the difference between home and inside the bubble, that’s different but it would not be as gratifying this year to be inside that as it would have been. And I got a taste of that on March 11 in Chicago when we covered them and San Jose. Because the rules were put in place that morning that we could not go into the dressing room. That Brian Boucher could not do any coaches interviews, that he could not do the Inside The Glass position if he had to access it by going into the bench area. That he could not enter the Inside The Glass position through team dressing rooms, because at some places you have to do that.

So we were getting a taste of what it would be like and were we going to complain? No. And we sure wouldn’t complain now because we realize this is what is absolutely necessary to keep these playoffs going as smoothly and wonderfully as they’ve gone.

In April, NBC made a video of a message you gave staffers during a conference call that was really reflective of the moment with the pandemic. What made you want to put that speech together and what was it like to see it reach viewers later on?

I was invited to do that at a meeting of staff just to close off the meeting and Sam Flood, who was in charge of the meeting, thought that would be a good thing to put to video. So five people worked very hard to put that to video and put it out there on one of our past historic telecasts and it was just how I was feeling at the time.

I think we were all missing the sport and looking forward to that time when we would all get back together again. But that was at a time where we had no idea of whether we would get back together again this summer and also the circumstances that would be prevalent at the time. I guess I was just trusting that I would be a part of that and that there would be some risks involved for somebody that was my age.

There was a gentleman by the name of Lamoriello that you may have heard of (Islanders president Lou) who was general manager of the Devils. He used to say ‘Michael, before you make any decision, look in the mirror and look at your birth certificate.’ And so I’ve remembered that, it was probably 15 years ago that he said that, and of course we’ve had a good laugh about it since then. But it was one of the decisions I had to make later in the summer.

NBC has been wonderful to me to do all of this equipment, and they also said ‘do not do anything that you are not comfortable with.’ And the fact that they’ve chosen to let me do these playoffs right until the end from my home is not a tribute to me, it’s a tribute to them.

I’ve been asked by several people to ask you whether you have a list of words or phrases you keep to keep your vocabulary so varied on a broadcast.

No! (laughs)

That’s one of the great myths of all time. I never have anything written down and I never have written words down to use. It’s just my vocabulary. The dogs don’t understand me sometimes. But, yeah.

I had a fifth grade teacher. It’s kind of an old story, her name was Una McClurg. She said that any word you use five times becomes yours for life. And I was actually told by an announcer, he did a year with the Capitals and just recently passed away. His name was Lyle Stieg. When I was just getting into this line of work he was a fellow broadcaster in the IHL and Dayton and I was in Port Huron and he said if you can come up with different ways to say many of the repetitive things that happen in hockey games it will help you because otherwise if every time the puck’s dumped in you say it’s dumped in, you’ll drive people nuts.

So I didn’t write things down, I didn’t write words down. But it’s just how I talk. I tend to use different ways and try not to repeat different ways of the same thing. So that’s one of those myths. I don’t have anything written down. And once I’ve used a word for the night I try not to do it over again.

I try to use “blockered” more instead of “waffle board” these days because in times past the waffle board was a more popular way to describe a blocker a goaltender uses because at one time it was brown, like a waffle. And it had rivets in it that used to look like the divots in a waffle. But then they started to get colored ones so the bright white ones and red ones, they no longer looked like a waffle. It became an archaic phrase so I don’t use it as much anymore.

As you can probably guess I grew up a Buffalo Sabres fan and really fell in love with hockey listening to Rick Jeanneret and Jim Lorenz.

Yeah, as you should! You had two wonderful ones there to listen to.

I think I learned more from Lorenz about hockey doing color than anyone else in my life.

I guess you would! Especially a steady diet of him every night, doing the games. Jim is a wonderful guy.

I think about that when it comes to broadcasting, especially on a national broadcast. Is there a balance you actively consider between educating people and giving them new things to learn or possibly considering, especially later in the postseason, that people watching might be newer to hockey?

Yeah, you try to balance that. And I’ll tell you what Sam Flood tells us, he’s very conscious of this. And he reminds us on the days of Winter Classics, Olympic Games, Game 7s and Stanley Cup Finals. That the audience is going to broader than it ever is for anything else.

So Winter Classics, which are New Year’s Day. Game 7s, Olympic Games and when you get to the Stanley Cup Finals. You’re always going to have a broader audience and you don’t want to talk a lot of shop. Yo want to make sure that you don’t leave anybody out that might be fascinated by this because we know for a fact that a lot of people jump on to these playoffs because of what battles take place and how it’s every other night and all of that lore I was sharing with you earlier that people just love about the playoffs.

So those are special times where we are more conscious of such things like mentioning where a player is from, because it only takes a half second to do it. Sean Coutourier, born in Arizona. It doesn’t take long. Ah, he’s American? Because some people think all of these guys are from Canada or they’re born in Sweden. But you throw that in because not everybody knows that 44 percent of the players are from Canada, 30 percent are Sweden, the rest are the U.S. and so on et cetera.

This year in particular has been fascinating with a pandemic and a national conversation about race and police relations playing out across sports. Some have been critical of the NHL in particular for lagging behind other leagues in addressing some of these issues. I was wondering if that’s something you noticed as well and if it was maybe the Canadian influence on the game or the bubbles being held outside the US that impacted that, or something else like hockey culture making players less willing to stick up?

No, I think they’ve caught up remarkably. And if you look at some of the quotes over the last four months, this is a culture that — I don’t know what was in the past how it compared to others. And one of the things that was always said is that there aren’t many players of color in hockey and it was something that just wasn’t addressed. Well, they’re addressing it now.

You see what Braden Holtby had to say and the comments Bruce Cassidy had, and many of them came during the quiet time where no games had been played and training hadn’t even begun. We can all address the past and the things that maybe we didn’t see or maybe didn’t do at that time, but the present is what’s most important and the present is becoming more vibrant all the time and more active all the time. And I’m very proud of that and to be associated with a game that is addressing it.

It’s been fascinating to see how different leagues are handling these situations and embracing social justice messaging. As someone with a big hockey background working for a site that focus so much on basketball the differences are notable, but I think you’re right that things have changed considerably in recent months.

I think the thing, too, is that it’s a different sort of animal in that we have 13 foreign countries represented in the last eight teams. That doesn’t excuse them by any means. But it does mean it’s a more diverse culture to begin with, and so sometimes these things don’t get addressed as quickly. And they have been addressed now, and they have been by people such as Zdeno Chara from Slovakia. The birthplace does not matter anymore.

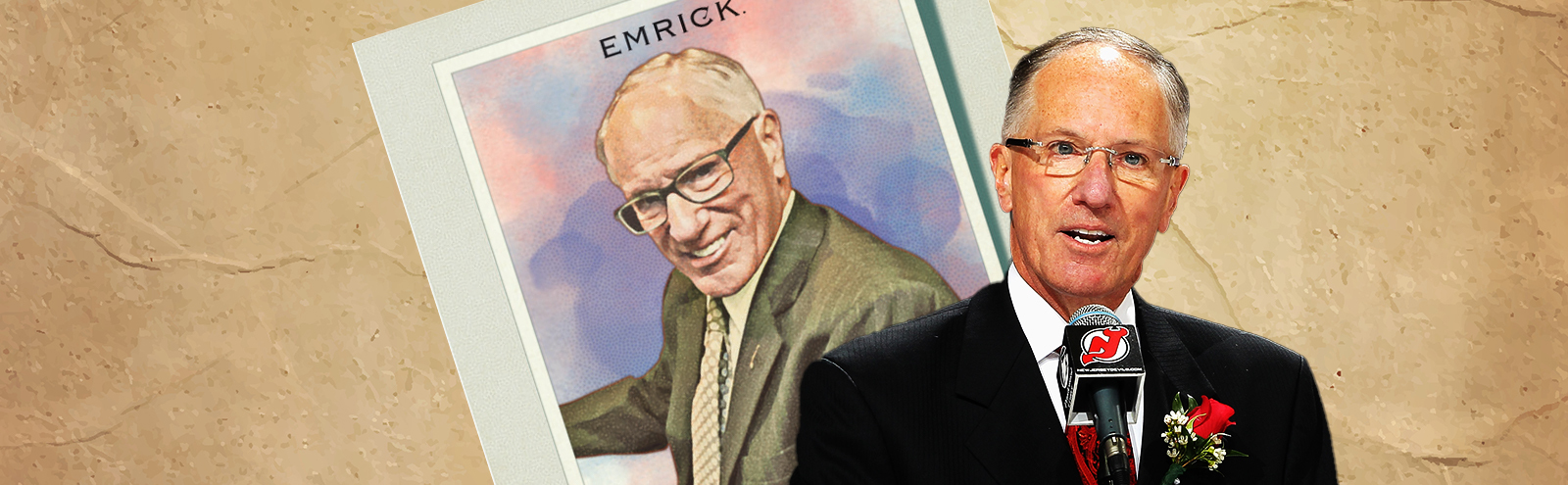

I have to ask you about baseball, and getting a card in the new Allen and Ginter set. You’re a huge baseball guy, what’s this mean to get your own card?

I’m 74, and as a bubble gum-blowing youth in a rural Indiana town of 600, LaFontaine. I grew up in that town of 600, I had a newspaper route and was obligated to save a certain percentage for church, a certain percentage for savings and the rest I could spend on what I wanted to spend it on. And I spent it on Topps baseball cards. From 1953 and 57. Now, sadly, before the craze hit which made the value go up my mom asked when I was in college what I wanted to do with those. They were in a cornet case in the basement.

And I said ‘I don’t care, do what you want.’ So she sold them to an antique dealer, and there were Mayses and Mantles and Aarons, Snyders in that. She sold them for $80 and divided the money and we were happy with that. But the crazy didn’t hit for another two or three years, so they had no value to us. And I had no longer wanted to keep them.

So the reason I’m sending you a picture later of those cards is probably in 1985 I started hoping to try to regain some of my collection. All but the really inexpensive ones. And I’ve been able to get a lot of the common cards from those years of my Topps collection. And they wouldn’t want me to say this, but I did collect one year of Bowmans as well. But those are very important to me because they are part of an idyllic youth that I spent in rural Indiana.

We of course maligned them by putting them in bicycle spokes as part of an archaic culture you may have read about or the people at Topps have told you about, probably a person who was bald and grey and about to retire from the Topps company told you what he used to do with them as a kid: he put them in bicycle spokes and they’d make a real clacking noise. But that’s what we did when we were bubble gum-blowing youth in Indiana.

But I love those cards, and I just went down and pulled them all out. They’re in number order and I took a picture of them this morning and I’ll send it off to you.

What did you say when they came and said they wanted to put you on a card?

I was shocked, I had no idea that there would be any value in anything like that. I signed about 50 of those a day. And I’ll tell you what was in the back of my mind. My brother is a big Dodgers fan going back to Brooklyn days. And he’s a very big Duke Snider fan, and twice I found autographed baseballs with Duke Snider’s autograph on them. And one was a little better autographed than the other. And the man who sold me both of them said that Duke had had a long day of signing and was tired. And now I understand what that meant and I decided I would only sign about 50 cards a day because I wanted the signature to be good. And if I just tried to blow through and do all of them at once that somebody wouldn’t get a very good autograph because I was just trying to gun through it.

So it took me about a week to go through all of the cards that they sent me so the signatures are good. I think that they’re legible, I wanted people to be able to read all the letters. That’s one of the things I admired about Gordie Howe’s autograph: every letter in Gordie Howe’s first and last name was just like he was probably taught in grade school.

Yeah, actually I have a Howe autograph from about 10 years ago somewhere in my parents’ house and you’re absolutely right. It’s remarkable how good the handwriting is. Because mine is not. I’m a journalist so I’m allowed to have bad handwriting.

Just like a doctor, right? [laughs]

I have to ask a Pirates question.

Well, we won last night. We’re at about one win for every three games which, for the amount of money that we’re paying players I guess that’s probably it.

That actually leads me up to the question nicely. Is there any hope in the Pirates and what they’re trying to build in the future?

I think there’s at least an optimistic culture. I loved Clint Hurdle, I thought he was a very positive guy. But in any situation after nine years or 10 years a change is needed and I think they’ve gotten that. I think they probably got new direction in the front office, too. But I’ve been a fan since 1959 and I’ve had a chance to be around three world championships. I’m proud to say I know a lot of the guys that played on hose teams and I’ve gotten the chance to meet them. And that means an awful lot to me. I hope that there are people in Pittsburgh that get a chance to say the same thing when they’re my age. I don’t know if that’s going to happen because as you know you need to spend money in order to have a good team unless you want to take a roll of the dice and hope that you’re Kansas City every once ever 50 years.

So I hope for the sake of the fans of Pittsburgh that they’ll get what I’ve gotten in my lifetime, which is three world championships. And a chance to meet some of the guys that are on it.