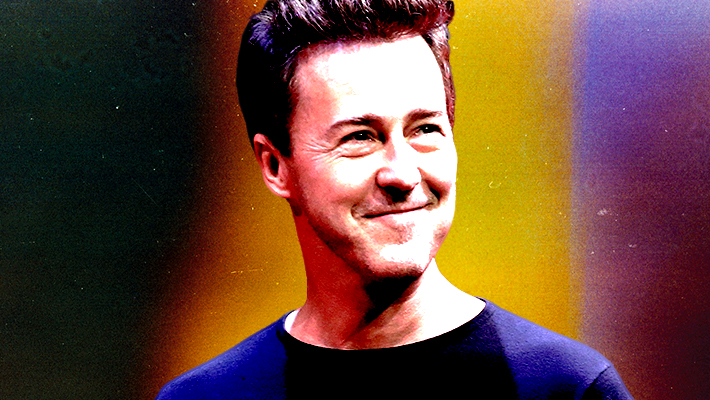

Edward Norton is just one of those actors who can connect with people. When people talk about their favorite actors of the last 20 years, he’s a name that comes up extremely often. Yeah, I’ve heard the stories about in-fighting and rogue edits, but let’s be honest here: most of the time one of those stories pops up it’s about a movie that’s good. So as a consumer of movies, why on Earth should I care about creative differences as long as the product I paid for delivers? And, way more often than not, Edward Norton delivers.

Though what is odd is just how long it’s been since Norton has directed, the last being Keeping the Faith way back in 2000. When you talk to Norton, he’s so meticulous about what he wants out of a film (which, frankly, comes as no surprise) it’s shocking that it’s been 19 years since his last and only other directing gig. Though, Norton has been trying, on and off, to get Motherless Brooklyn (based on the book by Jonathan Lethem, with the setting shifted from the 1990s to the 1950s) made for over 20 years. Yes, by definition it’s his passion project and, yes, Norton is an extremely passionate guy. When I met Norton at a hotel in Midtown Manhattan, he was brimming with excitement. This thing, this project, he’s been working on for 20 years, is finally a reality.

When I met Norton, he was quite friendly, but had a look of slight skepticism on his face. Basically a, “What’s your deal?” look. And, frankly, I found myself appreciating that because, if I were in his position, I’m fairly sure I’d be the same way. But the interesting thing about Norton is as he talks, he riffs on his past filmograpgy and any topic he might be thinking about that day, so one second we were talking about Fight Club, then The Incredible Hulk, then commenting on Martin Scorsese’s opinion of Marvel movies.

Edward Norton: What’s going on?

I don’t know why I still have this almost empty cup of iced coffee…

Because on your own recording, you want the sound of of you drinking it.

Yes, I do.

It’s all such a blur. Tell me a little bit about yourself.

Like what?

Who you write for…

Uproxx.

Yeah, I don’t know much about it.

Last time I interviewed Christian Bale he asked if it was a drug site.

“Yeah, we’re Silk Road.”

I know how much you’ve struggled to make this movie.

Yeah, there’s a coexisting sensation of satisfaction and just the settling contentment of a thing that had been rattling in your head a long time. Like having been not just resolved, but I watch it, and it’s as close to the movie as I had in my head as I could hope. And in some ways, I’m pretty delighted by the ways it transcended what I ever had. Like the music, which always comes in very late phase, you know?

How so?

I had some weird ideas about a mashup of things I love, between Radiohead and jazz. If the film is working, it really works when the music comes in. And then suddenly, you’re like, “Oh, my God. Oh, my God.”

The book is set in the ’90s, but you set the film in the ’50s. Is that the one detriment to not having it in the ’90s? That you couldn’t use actual Radiohead songs?

No. I mean, number one, they wouldn’t let us. Number two…

Well, number one seems like a good enough reason not to.

Yeah, there was talk at the time, because there was mutual admiration. There was also talk of using OK Computer almost as the soundtrack of Fight Club.

So we’d be watching Fight Club listening to “Karma Police”?

Yeah, well, we were always obsessing on the synergies. Like, remember the line, “Pour me out of the aircraft”? And there’s that scene where he imagines the plane evaporating around him and falling out?

Yes, that scene is horrifying by the way.

Yeah, it is.

As someone who doesn’t fly very well to begin with…

Yeah, that’s not a scene I particularly like looking at either.

I almost watched Fight Club on a flight once, then remembered that scene being in there so I didn’t.

Really?

I’m sure that scene is not in the airline version.

It can’t be.

I don’t even want to risk it.

[Laughs] Not even in Jet Blue Mint! The hippest first-class unedited films in the world. I doubt they show that. But the short answer is, no. I love jazz, and my reach out to Thom Yorke was, Thom loves jazz. Loves Mingus, in particular. The dissonance, as you might imagine, the more experimental stuff. But I said to him, “Look, I know this sounds weird, but I almost want you to be the Billie Holiday of Lionel’s mind.”

Here’s what I don’t get, because even listening to you talk about this, you’re so meticulous about film and what you want — why has it been 19 years since you directed a movie?

I didn’t intend it that way. It’s really funny, because I met Warren Beatty before I did my first movie. I think he knew that I’d worked a lot with my friend, David McKenna, on the script of American History X and he really liked that. We got talking, and he said, “My advice, don’t do what I did.“ He goes, “I started too late, and I took too long between them.”

Then you took longer than he did between Bullworth and Rules Don’t Apply.

I know, I know. I mean, I got the book. I didn’t even start trying for four or five years because I made Fight Club. Then I directed a movie.

Keeping the Faith.

I went on into another thing. And so, I didn’t even start to touch it. So, to say I’ve been working on it that long is not even true.

Right, I didn’t think you’ve been alone in a cabin for 20 years.

And then there was a period where I was ready to make it… If you want to call it the hard period, there was a frustrating period. It took me a good five years from when I finished writing it, to, by hook and by crook, assemble what I needed to do. I don’t want to say I didn’t have enough? I think I could have walked over to Netflix and gotten double the budget and gotten everybody paid.

Well, why didn’t you? Scorsese did it.

Well…

You seem to really like what Netflix is doing.

Very much. I think sometimes people make too much out of people’s comments. I heard, I didn’t read, that Scorsese said something about the Marvel movies? Or something? And then people are doing all this stuff?

Yeah, he said he doesn’t consider them cinema, or something to that effect.

Right.

But he can say what he wants, whatever.

Yeah, and also, the man is in his late-70s. He has his relationship.

Yeah, I don’t think he’s seeing Ant-Man.

No, but also, people have to grow up. People’s reactions are reflections of their insecurities, not what he’s saying. It’s like, hey, the man’s whole life is in films, and he has a certain view of it. It’s like, that’s okay, you can live with that.

I agree.

You can live with that.

It’s not going to affect the superhero industrial-complex.

No. And it’s also, by the way – though someone could defensively take it at that – you have to listen to what he’s saying. He’s saying that in the context of his life and in his experience, the things he relates to are that, you know? And it’s like by the same token, Steven Spielberg said things about Netflix. I couldn’t respect him more, and yet, I don’t totally agree. I think, for instance, there’s not a movie studio in America that would’ve made, or invested, in the theatrical release of Roma at the level that they did. Forget that it ever went on the streaming service. There’s not one boutique art-house label from a studio that would’ve either made the movie.

Cuaron has said that. It does not exist without Netflix.

Nobody ever gets it better than The Onion. Read The Onion piece about the Spielberg/Netflix thing, because it’s just really funny. But the notion that we’re in an era of unprecedented opportunity for creators of every stripe, from every nation, every language, every race, every background – the opportunity for diverse points of view and storytellers to tell their stories has never had its equal to what we’re experiencing right now ever.

Well, with you in particular… Most of a movie’s life is spent watching it at home. The theatrical window for any movie is a very small fraction of any movie’s lifespan. And you know that more than anyone because you had an interesting run in the ’90s of movies that didn’t find an audience right away, but then became beloved later, like Fight Club and Rounders. You were in a bunch of movies where people just love them today, but not everyone saw them in theaters.

American History X was like that. Although, it’s always funny, there’s always the narrative around a thing. It’s like Box Office Mojo has the budget of American History X wrong. It cost $8 million, and they’ll write that it cost $30, or something like that, right?

It’s always confusing because I never know if these numbers include marketing.

No, no, no, the budget of American History X was about $8 million bucks, and we made it for that. And then it didn’t do super-well in the United States, but it did really well in Europe. And then it also did really well over time. And it was one of the things, where, hey, if you make a movie for the right number, then you can make a challenging film. Because in those days, with the DVDs and stuff like that, it had a chance to find its way to a happy place, and they were completely thrilled about it, right? Irrespective Oscar nomination, or anything like that, it actually did fine for a hard-edged, cutting film. You know? It did fine. And they asked me what I wanted to do, and I got the book of Motherless Brooklyn. And that’s how I felt about this. In some ways, I was very affected by Reds. I was very affected by Do the Right Thing. I was very affected by films that a writer, director, actor made and that talked about America. Forget Citizen Kane, I think Unforgiven is a great American film.

That’s a great example.

You could call Unforgiven Western-noir, because it really basically says, “Hey, all the heroic narrative of the cowboy and the West, it’s really there’s a lot of dark and seedy shit.”

My other favorite thing about that movie is at the time people were treating it like Clint Eastwood’s swan song. “He’s going out with a great one.”

Right, I know!

And it’s like here we are 27 years later…

40 films later.

And another movie coming out this year.

It’s amazing, it’s amazing. Do you know that Clint Eastwood never directed a movie till he was 41 years old?

Yeah, it was…

Play Misty for Me. But he was 41 when he started, and he’s made like 50. But I think the point is, I’m not trying to get extra credit, but if I’m Quentin and I can get $95 million to make my movie, maybe I probably would, too. But I knew that with Warner Bros., Warner Bros made Unforgiven. They made L.A. Confidential. They did Argo. They have a tradition, and my biggest champion was Toby Emmerich at Warner Brothers, and he literally said to me, “Look, we can do this. If you can do what we don’t know how to do, which is make this movie for $26 million net.”

I showed it to Warren Beatty, because Reds really meant a lot to me. That was a formative movie. At a certain age, you go this is a three-hour movie about American Socialists, with documentary footage in it, and it’s like I think it’s one of the really great films. And he told me everybody told him, “You’re going to flush your whole career on this film.” And they were like, “Nobody wants to see this movie.” And he was like, “Well, I want to see this movie.” You know what I mean? When I showed this to Warren, he goes, “Shit, what did this take shooting? 75, 80 days?” And I said, “No, no, I did it in 47, 48.” And he goes, “You’re a lying sack of shit.” He goes, “Thinking about it, I can’t really wrap my head around that, and I really admire that.” That made me feel good.

High praise.

All right. We’ll do some rapid-fire questions.

Okay, let’s do a rapid fire.

I’ll be short in my answers.

I have one The Incredible Hulk question.

If I’ll remember, but try.

The original opening had Bruce Banner in the arctic, he shoots himself in the mouth and then Hulk spits out the bullet. Whose idea was it to take that out? It’s grim, but that’s a great scene.

Yeah. Sometime I’ll flip you the script. Louis Leterrier and I were working from what I wrote. Sampson was in the movie. Ty Burrell played Sampson. But that opening, yeah, and a roar in the dark, in the glacier.

So you wanted that in there, right?

Yeah. But look, this is another one of those things, people should not foment negativity. People sometimes have different views of a thing, And you can respectfully disagree. It’s fine. It’s fine. I get tired of the click-bait conversations around it, because Mark Ruffalo is one of my great friends. I love him.

I don’t feel like that was a click-bait question.

No, no, no, not that…

Okay.

I’m just saying I think that people, they tend to take a reductive log-line out of any comment that you make. And when you look at the path they’ve taken and what they’ve achieved with this synthesis, it’s a completely valid point of view. That, let’s call it a darker thing, may not fit within that. You know what I mean?

It’s the second movie in. You had no idea what it was going to be.

And that could be as much me and Louis not having insight into what the larger thing is, you know what I mean?

So The Italian Job is still on cable nonstop. I know the circumstances around you being in it, you kind of had to do it to fulfill a contract, but do you look back at that and think, you know, under the circumstances, I’m pretty fucking good in that movie.

[Laughs] I’ve never, I can’t say I’ve ever seen that movie all the way through. But I’ll say this, same thing, in no way do I focus on the negativity. I was in the middle of a play. It wasn’t like, “This is a piece of crap.” It wasn’t that. I was doing a play that was very meaningful to me. It was an award-winning play and it was my theater company, and I just didn’t want to be yanked out of it.

That makes sense.

So it had to do with those kinds of things. Sherry Lansing, the head of Paramount, literally gave me my start in the business. So even though it was an argument with her, I love her to this day. You know what I mean? And more importantly, I went into it feeling grumpy because I’d been pulled out of a play to do it, but I loved Mark and hadn’t really gotten to know Mark before that. I became very good friends with Jason Statham. I’m still friends with him to this day. You know, great things came out of it.

My last rapid-fire.

Last, okay.

You’re one of the few contemporary actors who worked with Brando. On The Score, did you get to hang out with Brando socially?

Well, I knew him before.

Oh, you did? I knew you did the documentary later.

I knew him before, yeah. He was… I loved him very much. He was thoughtful, and poetic, and wounded. Knowing him in the later part of his life was very poignant. But I liked him very much.

You can contact Mike Ryan directly on Twitter.