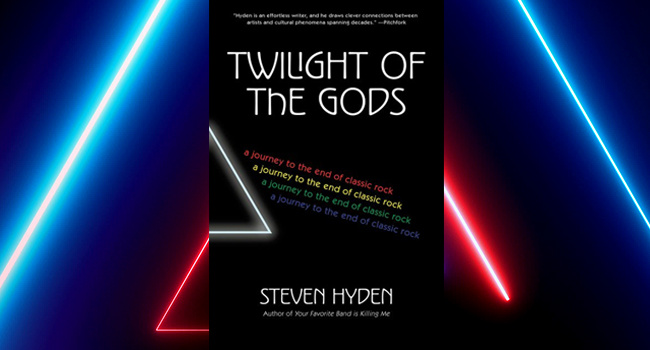

As someone who has the privilege of reading pretty much everything Steven Hyden has written about music over the past year and a half — and for many years before that — I was excited to finally get the chance to read his new book, Twilight Of The Gods>. The follow up to his first book, Your Favorite Band Is Killing Me, a treatise on the diehard face-offs between bands across the decades, this time around Hyden is more concerned specifically with rock legends, and the slow closing of an era where their defined pop culture.

Released a week ago today, in Twighlight Of The Gods Hyden traces the inception of the classic rock era, which in his estimation begins with the Beatles and Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in 1967, and ends with Nine Inch Nails’ The Fragile In 1999. Adopting a framework inspired by Joseph Campbell’s The Power Of The Myth, Hyden takes the reader on a hero’s journey through the many highs and lows of these mythic figures, from Led Zeppelin to Bruce Springsteen to Bob Dylan — and plenty of other minor characters in between.

As music criticism, and indeed, the music industry as a whole, seeks to grapple with the overwhelming dominance of white male figureheads in the 20th century, Hyden offers a clear-eyed perspective on an already-dated era that is quite obviously winding down. By explicitly interacting with the way these old preconceived notions dictated power and glam in rock and roll culture, Hyden offers a very modern take on some age-old figures, while also remaining self-aware of his own place in the system. Even as the book reveres a bygone period, it also looks to the future with sharp analysis, funny insight, and a sense of wonder that is rare to find in any kind of writing, let alone music criticism. (Read his excerpted chapter on dad rock for a taste of it yourself.)

Last week I talked with Hyden about a couple key elements of the book that stuck out to me, like mourning our rockstars, what a rock band even is anymore, and if some figures loom larger in culture than the era itself. Read our conversation below.

The book is about the end of classic rock, something that I think we’ve seen culture grapple with over the last couple years as icons like David Bowie, Prince, Chris Cornell, and Tom Petty have died. Did writing this book help give you some personal closure? Do you feel like just grappling with it over the text helped you accept the end of this era?

I don’t have closure in the sense of being done with the music. I’m still really interested in this era, and I feel like I’m gonna basically go down with the ship. One of the points of the book is that people use classic rock, and probably pop culture in general, to help understand their own lives. With classic rock, specifically, it’s become is a way for people to process their own mortality. When David Bowie or Prince passed away, I think the reason why that impacts people is that they feel like a part of their own lives has disappeared, and it’s not coming back.

It becomes a way to think about these pretty heavy topics that we spend most of the day trying to avoid. This book, especially towards the end, becomes about processing mortality, and the idea of impermanence. There’s a great work of art that you think will stand the test of time. There’s going to come a time for everything where it finally disappears. There’s a sadness to that, but there’s also something beautiful about creating and living in the face of that.

As someone who doesn’t necessarily have deep knowledge of this era, I liked that you gave it a beginning with the Beatles and an end with Nine Inch Nails. How and when did you set up those goalposts while writing the book?

With talking about Sgt. Pepper as the beginning of [this era], I relied on a lot of books that I’ve read from people talking about the changes in rock and roll from the ‘50s up to the late ’60s. In the ’50s, rock and roll was basically pop music; it was the music that teenagers listened to, and the songs were about teenage topics: School, first love, going on dates, stuff like that. If you listen to Chuck Berry and Buddy Holly and all those people that’s what their songs are about. Then you get to the late ‘60s, and bands start thinking more in terms of Serious Art, with a capital A, and making music for the older people, and maybe more self-conscious people, people that think about music in terms of literature almost. It seems like Sgt. Pepper is an obvious beginning point to that because you have the Beatles, who start out as a traditional rock band making songs like “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” and “She Loves You,” very much in the style of early rock and roll, talking about teenage love.

The early Beatles aren’t all that different from One Direction now, even in terms of how they sound. One Direction is basically a pop-rock band. But then when you get to the later Beatles it’s more elaborate production, it’s more philosophical. You can call it pretentious I guess, it definitely has that element. A lot of the music at that time, a lot of the rock music, starts to split itself off from pop, in a very deliberate way. So, that was kind of an obvious beginning point. Then to talk about Nine Inch Nails, I really think about the classic rock era as being a 20th-century phenomenon. Not so much the music, necessarily, it’s not like I think the music got worse, it’s more to do with the industry. Basically, by the end of the ’90s you have Napster really become a huge thing in 1999, and that is the beginning of where we’re at now, where the internet is the hub of how we get most music for most people.

One of the things that comes up early on in the book is how different radio stations helped shape the definition of “classic rock.” What force do see functioning in the same way as the tastemaker for rock as we move forward? I don’t think it’s necessarily terrestrial radio as much. Do do you think there’s any sort of tastemaker that’s combing through new rock in the same way that existed throughout the era that you’re writing about?

One of the issues rock music has had in this century is that it doesn’t have an identity. People don’t really know what it is. I find myself having conversations with people all the time about ‘is this band a rock band or not?’ It seems like everyone has an idea of what a rock band isn’t, but defining what it actually is really tricky. There’s people who say Radiohead isn’t a rock band. There are people who say the National isn’t a rock band or LCD Soundsystem isn’t a rock band.

People have this very sort of narrow idea that a rock band looks like a cross between the Strokes and Guns N’ Roses, that they have sort of a punky, hard rock sound, and that they smoke cigarettes, and have tattoos. I go the opposite way, I tend to be really broad with how I define rock artists. But, most country music right now is basically southern rock; like Chris Stapleton, to me, is way more in line with a ‘70s southern rock sound than a classic country sound. I think Taylor Swift is a rock artist. I think Adele has elements of rock in her music. It’s everywhere, which makes it invisible. It’s so hard to spot, even though there’s elements in almost every kind of music.

I think a great example of this in your book is Phish. When I got to that I realized I don’t think of Phish as a rock band. The I had to pause and wonder why not, when, arguably they’re one of the biggest ones!

The term rock is so generic in a way that people feel like it’s not specific enough to call anyone rock. It becomes like a death by a thousand cuts. There’s so many different sub-genres and so many different adjectives to describe band with this term that is 60 years old now. It just falls out of favor, even if the music itself has elements of what we would have formally associated with that term. It’s kind of the opposite of what happened maybe 30 years ago where everything was called rock and roll or it was put under that umbrella.

There are a couple figures that pop up again and again in the book. Springsteen is one of them. Led Zeppelin are another, obviously, and then there’s Bob Dylan. With Dylan coming up so many times throughout the book I’m wondering, are there some figures that just loom larger than classic rock at all, and is Dylan maybe one of them? Springsteen may be one of them. Is it possible that some of these icons are bigger than that era?

Yeah, absolutely. I think Dylan, to me, is the one person who will be remembered the most. I was talking about this to someone the other day about, we were talking about Bob Dylan in concert these days, and how it’s very hit or miss to see him live. My attitude now, at this point, is any time he’s within driving distance, I’m going to go see him — because it’d be like if William Shakespeare was putting on a play in your town. One of the great artists of all time.

I really do think that Dylan is like the Shakespeare of now, he’s like Abraham Lincoln, or Mark Twain. These eternal, iconic figures of history, and certainly of American history. Honestly, he’s the person I can’t imagine the world without the most. You could take anyone in the book — what would it be like if there no Rolling Stones? Or no Bruce Springsteen? And that’s really weird to me, but a world without Bob Dylan to me, is the most inconceivable. He has touched every corner of music.

Toward the end of the book when you’re discussing this often invoked and the sometimes maligned phrase, “rock is dead.” Do you think that phrase itself is gonna die out as a new generation of rock lovers and new bands come into the picture? Or is that something that’s gonna always hang over rock, the death of classic rock or this era that’s passed? Do you think that’s always going to be looming there?

A lot of the time when people talk about how “rock is dead,” it comes from people that are getting older, and they feel like the music they loved when they were younger is no longer interesting to them, so then they’re projecting their personal feelings onto the genre itself. There’s also an idea too, that’s more of a tribalism idea, that rock and roll should die, and it should be replaced by something else. Whether it’s hip-hop, whether it’s electronic music — those are the two big genres that are often posited as rivals to rock. If rock is second to one of those, does that means it’s done? In reality, there’s no reason why these things have to be in polar opposition to each other. People say country music is dead all the time. That stuff’s ancient. I think those tensions exist everywhere. There are certain specific things about rock that make it more susceptible to that. There’s almost like an ideological drive to bury it among some people, but it’s never gonna die, man.

Twilight Of The Gods is out now via Dey Street Books. Get it here.