By 2014, it was widely agreed upon that television had thoroughly entered its golden age. The era of prestige programming was at its creative peak, with shows like The Sopranos, Mad Men, Breaking Bad, and Deadwood having undeniably taken their place among the medium’s upper echelons of acclaim. It seemed as though a formula for successful and serious television had been formed: stories crafted by a new breed of auteur, all-powerful writer-showrunners who told stories of complicated men whose torment and often destructive problems revealed wider issues of life, death, and existential panic. The formula was so familiar that writer Brett Martin wrote a book examining it titled Difficult Men. TV had remolded itself into the images of these difficult men, from Tony Soprano to Don Draper, Walter White, and Al Swearengen. The great pretenders had come and gone, as had more than a few rip-offs that crashed on arrival. As quickly as it had come to dominate our small screens, the Difficult Man had become a trite cliché. It needed to be taken down a peg or two. Enter BoJack Horseman.

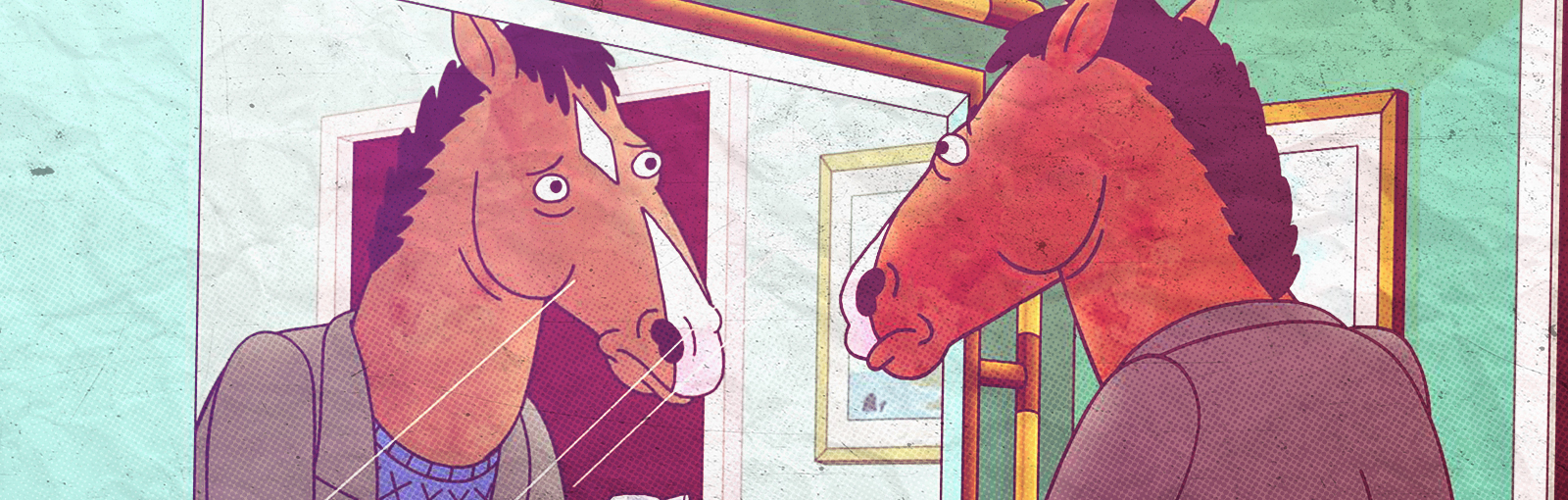

Netflix’s first original animated comedy series arrived on the platform without much fanfare. This story of a washed-up sitcom star who also happened to be a horse struck some critics as too crude, too invested in in-jokes about Hollywood, and too on-the-nose in its parodying of modern TV anti-heroes. BoJack, voiced by Will Arnett, was the former leading man of a terrible but wildly popular family-friendly TV series called Horsin’ Around (think Full House with way more saccharine lessons to be learned) who spent most of his days drinking and hating. The set-up seemed obvious: a dramedy about the emptiness of celebrity told through the lens of a man tormented by it, an anti-hero whose flaws were obvious, yet the audience felt compelled to stick by. The jokes flowed freely, and the sketched-out animation style, replete with anthropomorphic animals and laden with sight gags in every scene, seemed primed for laughter. In many ways, it felt like the comedic comeuppance to the oversaturation of Difficult Men, with BoJack, a paunchy upright horse in outdated knitwear with a penchant for vodka and profanity, acting as the ultimate takedown to that assembly line of male characters’ self-pity and damage.

And then things suddenly changed.

In the penultimate episode of the first season, BoJack attends an event where his memoir ghostwriter-slash-friend Diane is talking. He approaches the mic to ask a question and pleads with Diane to tell him that he’s a good person.

“I need you to tell me that I’m a good person. I know that I can be selfish and narcissistic and self-destructive, but underneath all that, deep down, I’m a good person, and I need you to tell me that I’m good. Diane? Tell me, please, Diane. Tell me that I’m good.”

There’s a long pause. A silence. Diane doesn’t respond. The episode ends. There’s one more episode left in that season, but this was a tipping point, a strident indication that BoJack Horseman had no intention of being your run-of-the-mill dramedy.

As the seasons progressed, so did BoJack’s arc and the show’s complexly layered intentions. Much of what their eponymous horseman went through wouldn’t have looked out of place alongside the likes of Draper, White, and company. BoJack tried a career comeback by playing his childhood hero, Secretariat. He tried to make amends to those he’d hurt over the decades. He met a young woman who he thought was his daughter but turned out to be his half-sister. He visited an old friend and grew close to her family, finding a sliver of peace in the process. Later, he even became the star of a Difficult Man prestige drama that delightfully tore to shreds the conventions of the genre even more so than BoJack Horseman had done for the prior four seasons. Yet something terrible always happened, and it was almost always BoJack’s fault. His addictions become increasingly crushing and his irresponsibility hurt practically everyone around him.

Moreover, the ripple effect of his devastation spread far beyond his own awareness. In one episode in the show’s final season, we see the ways in which BoJack’s behavior intertwines and leads to long-term consequences for his victims. A woman he attacked while blacked out on drugs struggles to navigate her trauma and ends up with a reputation for being a “difficult” actress. A female director whose career he essentially sabotaged struggles to find work (the series was always savvy in examining how the difficult label deifies men and punishes women.) BoJack’s sister Hollyhock finds out about a horrifying incident involving BoJack and some underage students. Long before this episode, it often became tough to even think of BoJack Horseman as a dramedy. The jokes were still there, but the intent had become far bleaker. Here, it became crystal clear. This wasn’t a show where things would end with a laugh.

There’s an implicit promise that comes with the dramedy concept. Audiences expect some kind of closure, a final chapter that offers a kind of catharsis for the viewer and peace of mind for the protagonist. It doesn’t have to be the happy-ever-after of a network sitcom, but we still crave the laughter, that releasing of tension that lets us know it’s all going to be OK. Even the Difficult Men dramas tended to lean towards this creative direction (with the obvious exception being The Sopranos and look at the outraged response that elicited from plenty of fans.) Couple that with the genre’s tendency to overtly sympathize with its anti-heroes and it seemed all too reasonable to expect the same for BoJack. After all, the show gave him plenty of opportunities to change, to improve, to learn his lessons and put himself on the route towards redemption. Despite it all, as a viewer, you find yourself desperate for BoJack to change and be happy.

But it doesn’t come, and slowly, you realize that he never deserved it. Diane was right not to answer BoJack: He’s not a good person, and that’s not something to admire or replicate or even mock. There was no redemption for him, and that reality felt like a betrayal of the dramedy in some strange way. By the end of the show, it was debatable whether or not you were even supposed to like BoJack.

What worked most about this long and agonizing protagonist arc was how it exposed television’s fetish for men like him. Even as prestige TV damned difficult men, it held them up as creative paragons for a new age of small-screen storytelling. They were grimy yet glamorous, bad yet cool, complex, and given layers of empathy often denied to characters who aren’t cishet white men. By the finale of Mad Men, for example, it’s pretty clear that you’re still supposed to see Don Draper, after everything he’s done, as some sort of hero. Walter White goes out in a blaze of glory. The only reason Frank Underwood from House of Cards’s narrative ended as it did was because of Kevin Spacey’s firing. It wouldn’t have been out of the ordinary for BoJack to giddy off into the sunset as a new man with a bright future ahead of him. Yet to do so would have overlooked that one man’s difficulties seldom happen in a vacuum, and they certainly don’t for BoJack. How do you prioritize a Difficult Man’s redemption when the devastation he’s left in his path includes dozens, potentially hundreds, of casualties? People died because of BoJack. How do you keep laughing?

In the series finale, BoJack hits rock bottom for the lord knows how many times in his life. Serving jail time for breaking and entering and with his reputation potentially beyond repair, he leaves prison for one day to attend a wedding. He sees the people who were closest to him during his best and worst times, and it’s clear that, while there’s a bittersweet piece to these interactions, these former friends have no reason to ever continue staying in contact with BoJack. There are hints of his life after prison. He could stay on the straight and narrow, but he very easily could fall back into old habits once more. The opportunities are certainly there for him to do so, but we’ll never see them. Still, the mere possibility of them hangs over the viewer as the show slows to its open conclusion. There’s no final punchline. The music doesn’t swell triumphantly. The cartoon cast doesn’t step forward for a bow or standing ovation. All that is left is the certainty of uncertainty, and in a medium built on the promise of closure, that’s a tough but necessary pill to swallow. It’s pretty difficult, isn’t it?