Earlier this summer, Mythbusters kicked off the second half of its 14th season on Discovery. And what a season it’s been! We’ve seen Adam and Jamie recreate the trunk-mounted machine gun from Breaking Bad, re-visit the ending of Jaws, and examine whether hands-free cell phone usage while driving is really the safer option. And what’s this we hear about another Star Wars-themed episode launching Sept. 5?

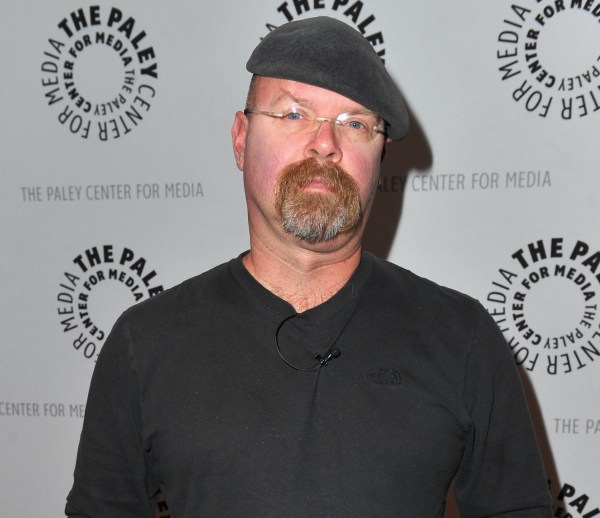

We caught up with Jamie Hyneman (the one with the mustaches and hats) and he gave us the dish on the evolution of the show, where the ideas come from, and the one myth that the producers of the show just won’t let him bust.

The coolest thing about the show has always been the insatiable curiosity that you two have — that kind of giddy ‘I wonder what’s possible’ energy. Did that become your brand at some point or is that just the way you two are?

That’s pretty much just the way we are. Whatever you see us do actually takes about five to ten times as long if we were just doing it without filming it. There is a little bit of premeditation involved about what we are doing and how we come across, but the fact is that it’s genuine at its core. It’s pretty much just us. We have to manipulate things a little bit to make sure that it is a coherent story, but fortunately storytelling has a beginning, middle and end and so does the scientific method.

Where do these ideas generate out of? Do you guys have a writer’s room? Do people email you ideas? Is it just random stuff?

It comes from all over the place. We have a team of producers/researchers that are always coming up with new material. Sometimes we take on things just because we find they’re interesting. There’s a lot of stuff that we’ve done over the years that has not really belonged within the realm of an urban legend or event per se, even though that’s the initial concept of the show. We take license in it now. Ultimately it’s just about us exploring the world at large… we look for things in particular that might have a counter-intuitive result, things that are funny or interesting and exciting in some way or another. But ultimately it’s just about us having an adventure exploring things.

With so much of content these days being about ‘how much can I get in three minutes?’ you guys continue to do very deep dives. People have really responded to that. Do you have any thoughts on why people have connected to the depth to which you take things?

It’s hard to say, really. I know we go against the standard approach to media and reality television in particular, but for me it’s like, why wouldn’t you want to watch thought-provoking material? We try not to present things that are long and drawn out and boring, but if you are watching something on television and you can be entertained, as well as get your juices flowing as far as understanding how the world works and so on, why wouldn’t you want to do that? You want to turn on the television and be bored?

You guys do such a good job of hitting those issues where someone says, “I didn’t really know I wanted to learn about this, but now that I see it I want to learn about this.”

There is a certain playful approach in what we do, and people like that. You think of play as something that children do, but adults do it too. They respond to playful exploration because that’s how we learn things when we’re children. It doesn’t mean that because we’re adults we’re really any different. There’s more to it than, well, we’re just not careful about we are doing and that’s why we are screwing around. We’re screwing around because it’s a very helpful way to get material.

What’s your origin story with being on television? Was that an end game for you at any point, or did it come about through a different series of events?

I was just trying to make a buck. When this came along I was like, “Well, I’ll give it a shot because you never know,” but it was the last thing that I thought would ever stick. I still have no desire to be in front of the camera. It’s the only part of the job that I like the least, and yet it seems to have worked. I am actually interested in what we’re doing. What’s important for me is the amount of stuff that I’ve worked on, in spite of the fact that the camera greatly slows down that process. We’ve seen things and we have an understanding of how the world works that is really pretty unique because of this continual trial by fire of understanding reality and materials and processes.

As you go through a show, are you constantly pivoting? Is the writing process constantly changing? Or is some of that what you’re are having to project into it?

Absolutely. It happens all the time. By definition we’re doing experimentation — we are not doing demonstrations. A lot of the things that we do we have a pretty good idea of how something is going to turn out before we actually test it, but we have learned not to be too sure of ourselves in that sense. A lot of times, especially with urban legends or something where there was a question involved that’s counter-intuitive, there is a reason for where it started. Sometimes those reasons will surprise you and we have to adapt the story to reflect on what actually happens. A surprisingly large amount of time, we go in and we have to do an about-face or take a totally new approach on because we don’t know what just happened, or what happened just doesn’t work for us in terms of our methodology — it doesn’t deal with what we just saw. It’s a very fluid process. Typically, at any given time we’ve got maybe three or four stories that are in the hopper that we’re working on, so if we run into a speed bump on one, we just shift to another and let the problem area percolate.

Do you have any pet episodes?

Yeah, actually. It’s like asking a parent which of his children is his favorite, but oddly enough, as different as Adam and I are it’s the same, and that’s the lead balloon. The reason for that is that it represents what, to us, is the most important thing. In an older episode we built a balloon out of lead foil that was .007th of an inch in thickness. It was 14 feet across and weighed 28 pounds. We filled it with helium and it flew. This is a material that is effectively like working with wet toilet paper. It’s really weak and heavy, especially when you get it in that thinness. What it takes to do that is what it takes to really understand any kind of a problem or do any kind of problem solving. You have to be able to internalize what you are dealing with. For us in that case, internalizing it was walking through in our heads what was going to happen when we tried to build this thing before we actually got there. Since it’s just a simple bag that’s shaped, it was simple enough for us to do that in its entirety. We had to visualize what was going to happen every second as we walked through that day. We identified something like close to 30 things that we never thought about having to deal with before we went through that process. The bottom line is that once we actually did the experiment it was kind of freaky, because we had already been there every second of that day and we saw everything that we anticipated. That, for us, is thrilling in spite of all the other stuff that we come across on the show—the thrill and the adrenaline rush of doing things and seeing them actually work for us.

Anything that has had to stay on the cutting room floor, or ideas that you wish that you could do but have been limited by budget or the idea not being viable in some way? Is there a white whale hanging out there for you guys?

We usually figure out a way of doing things if we are all aligned with it. I would say more likely there are things that individuals of us want to do that the rest of the team doesn’t agree with. For me, there’s one story that we did before that kind of touched on. It involved a baseball player hanging his arm out a train that was going in one direction throwing a baseball in the opposite direction at exactly the same speed to somebody on the side of the track. It ends up just dropping straight out of the air because the velocity has been cancelled. We tested that and it worked and all, but what I actually wanted to do was be the baseball. I have this concept of building this reverse-facing slingshot outside of a bus. You would just press the trigger and it would go off, so you would end up—bang—on the side of the road, dead still. For some reason they won’t let me do it.

The insurance company must have just loved that when that came across their desk.

I think we could get it past the insurance people. For some reason, Adam or the executive producer of the show doesn’t seem to be interested in it. What we do with a lot of those kinds of situations, if there’s an implied risk, is to work our way incrementally into it. You could run off the back of a trailer if it’s moving at five or ten miles an hour to see what happens. If you do that safely, what about twenty, or thirty, or fifty? And you can do things like test it with sensors and a crash test dummy. The problem is not the drop, because you can put this on the side of something very low as you’re going down the road. The problem is what happens when you interact with the ground if there is a speed differential. You remove friction, which is what motorcyclists do by wearing leather. If they hit the ground they slide. There are a number of things that you could do to minimize or potentially eliminate any possibility of injury. For me it’s a great story because on the face of it, it’s ridiculous or funny and potentially dangerous, but then when you start to break it down it’s actually not.