In the mid-2000s, my dad started going to Chicago every October for a conference. Each year, he wrote emails to my mother, sisters, and me detailing his love for the city. These letters — short, choppy snippets — told of late nights spent alone in smoky clubs listening to Chicago blues.

The surprise here is that my dad was never much for late nights. Or live music. Or smoky nightclubs. In fact, before he found Chicago, he wasn’t even a big fan of the blues. But for a week every fall, all that changed. In one email, he writes, “Didn’t get back to the hotel until 1 a.m., had to get up for the airport at 5.” This from the guy who would routinely fall asleep during the opening credits on family movie night.

Even though these emails told a story that differed greatly from the man I knew, for years they didn’t make much of an impression on me. I mean, I was glad to have pops happy, but he and I had so many things we connected over — fly fishing, basketball, food — that I didn’t really feel the need to dig below the surface about his time in Chicago. I responded to the emails and was excited for his excitement, but I didn’t ask too many questions.

Then, in 2014, my father died, with my sisters, mother, and I crowded around his bedside. After a season of intense grieving, the pain of his death shifted into more of a dull ache. Having lived apart from my parents since I was 18, it wasn’t the day-to-day missing that I struggled with, it was the permanence of it — the idea that I had years of missing him ahead of me.

It was around this time that I started digging through my dad’s effects. He had done a good job of leaving behind source material, and my mom had done an even better job of saving it. There were birthday cards and book inscriptions and old emails to reread. There were notebooks from his travels to decipher. Eventually, as I worked through his writing, I started to wonder about Chicago. I grew curious about those late nights — some of the only chunks of time in the last 40 years of his life when my dad wasn’t with me, one of my sisters, or my mom.

I decided to go on a blues discovery trip of my own. I would fly to Chicago and track down the clubs my dad went to. I would listen to the music and try to figure out what it was about the scene that captivated him so much.

Buddy Guy

It’s worth mentioning that I didn’t know much about “Chicago blues” when I arrived in Chicago. Because I’d heard the phrase “electric blues” and “Chicago blues” interchanged a few times, I could savvy out that these blues were played on electric guitars, versus the acoustic guitars favored by the old Delta bluesmen. But I didn’t know the history and couldn’t name any of the legends of the Chicago scene besides Buddy Guy and Muddy Waters (and both of those came from my dad’s emails). On the other hand, I didn’t really feel like I needed to do any research. My dad hadn’t come home from Chicago as a blues scholar, he’d simply found himself entranced by the music.

That would be my litmus test: Did I like the sound?

My first night in town, after dinner with a friend at Lou Malnati’s Pizzeria, I headed to Chicago B.L.U.E.S. Bar. It was a neighborhood spot. A little hole-in-the-wall that smelled vaguely mildew-y. This only added to the charm, as did the kind service, the cheap drinks, and $5 cover.

On stage, was Vance “Guitar” Kelly and The Backstreet Blues Band. It was a six-person group, and those six made up at least a fifth of the total crowd. Still, Kelly performed like he was playing Soldier Field. He and his bandmates surged with energy — playing a combination of classic covers and originals, carving out solos for every person on the tiered stage, improvising with the audience in one moment and seeming completely lost in the music the next.

After chatting with a few of the band members at intermission, I got the idea that The Backstreet Blues Band had never broken big outside of Chicago. I imagined that they all had day jobs, and that some of their co-workers might not even know that they played in a band… but on stage, they ran the joint. They were wild and explosive and brimming with life. It was easy to see what had appealed to my dad so much.

There was an energy to the music that resonated.

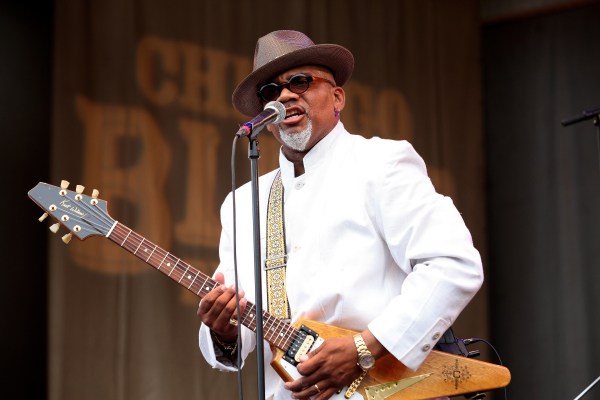

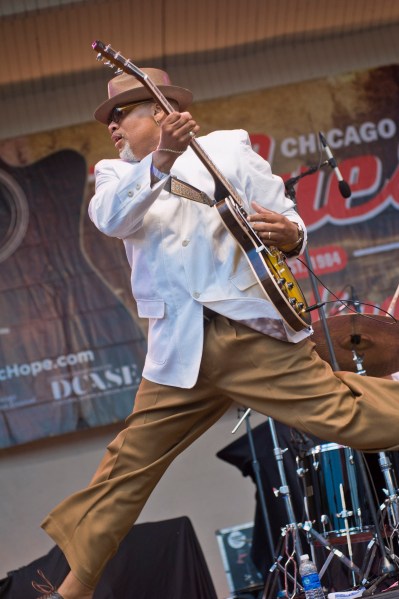

Toronzo Cannon

An interesting note about my dad’s emails from his nights spent exploring the Chicago blues scene: He went alone. He was always adored by his co-workers, so it’s pretty easy to assume that this was an active choice. He wanted to be alone. I see that appeal. There is something about a night out, alone, in a strange city that holds endless potential. There is something inherently exciting about being completely in charge of your own evening. I can’t explain it in precise words, but I think this is what made my dad — a man who liked to get his sleep — stay out until 1 a.m. By not being pressured to stay awake, he felt free to stay awake.

So it was, that I decided to be by myself the next night when I went to Buddy Guy’s Legends — my dad’s favorite club. I wanted to experience the famous spot the way my dad did, without the comfort of a friend to chat with, completely in the moment. When my dad went to Buddy Guy’s for the first time, he saw the man himself take the stage. He wrote of the bluesman’s iconic white flat-cap, his striking stage presence, and his rapport with the crowd. Though the hat was different, I found those same qualities in Toronzo Cannon.

In the world of Chicago blues, Cannon is well known (although he, too, mentioned having to keep a day job). His songs tell stories of unfaithful spouses (lots of them), ugly divorces (from the lack of fidelity), and hard times. And yet the musician has this playful way about him, and tongue and cheek style that makes you feel like you’re being willingly played with by a master storyteller. After a song about dating younger women, Cannon shouted out his wife. This kind of musician-as-character is common across genres, of course, and always has been, but Cannon’s stories are so rich with details that it would be easy to believe him if he didn’t occasionally remind you that it was all part of the act.

Cannon’s music is a master class in what “Chicago blues” actually is. Many of his songs start out with a cappella singing or delta-sounding riffs, then soar headlong into long, reverb-filled solos. By listening to it, you can sense the northward migration of musicians, headed to a big industrialized city, reflecting their new, scruffy, jagged-edged environment in a grainier, electrified blues.

Listening to Cannon and his band never got old for me. It was so easy to get lost in the frenetic solos and the richly detailed storytelling. Between songs, I thought of my dad. I felt like him — exploring a genre of music that has played a big part in defining Chicago, owning my own destiny for the night, never in a rush to go anywhere, tapping my feet with excitement as the next song began to play.

In the brief moments between songs, I felt more connected to my dad than I have since his death. It was late, I had an early flight to catch, there was packing to be done and work the next day. But just a few feet away, on stage, stood a musical virtuoso, ready to play his heart out. As long as I kept watching him perform, the night still held endless potential, anything could happen…

I decided to stick around for one more song. Then another. I am, if nothing else, my father’s son.

— by Steve Bramucci

Brought to you by Jim Beam