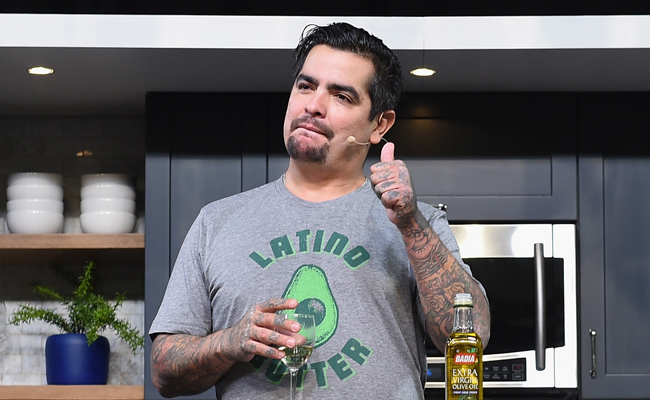

If you’ve watched any Food Network in the last five years, chances are you’ve seen Aarón Sánchez, the El Paso-born Mexican food chef with the calming voice and penchant for over-pronouncing Spanish words. Sánchez is a regular Chopped judge, battled Morimoto to a draw on Iron Chef: America, and co-hosts Masterchef on Fox, among other TV gigs. If you’re particularly sharp-eyed, you may have even noticed the tattoos that cover his hands.

In fact, though he’s less well-known for his tats than, say, the frequently short-sleeved Michael Voltaggio, Sánchez, normally shot with long sleeves sitting behind a table, is almost totally covered, inked continuously, basically from the neck down. The artwork was easy to spot this past week at the Fire It Up! event at the Grand Wailea in Maui, which brought together a number of famous chefs for a big barbecue (which I also got to cover, not a bad life).

After the demonstration, I sidled up to ask him some questions and he was happy to talk. Which is another thing you notice pretty quickly about Aarón Sánchez: he’s happy to talk.

“I actually co-own a tattoo shop in New York called Daredevil,” Sánchez told me. “They had just re-legalized tattooing in New York. It was banned from 1961 to 1997, I believe. A lot of that had to do with, obviously, the AIDS epidemic, and drugs, and they wanted the tattoo artists to be certified on how to handle needles, which is good. Anyway, I opened my first restaurant in ’98, ’99, and they had a tattoo shop across the street. I befriended these tattooers, became dear friends with them, and we would barter food for tattoos. So, I was ahead of the curve. Now it’s cliché for a chef to be plastered with tattoos.”

I asked if he has any carrots or radishes on his forearms (no offense, Brooke, it was just the first thing I thought of). His arms are so ink-covered it would’ve taken me a few minutes to find a root vegetable, even if he had one.

“No, I don’t fall for that,” Sánchez said. “I’ve gone on record as saying ‘if I see an asparagus stalk I’m going to puke in my mouth.’ I try and tell cooks that it doesn’t make you cook better. I’m just throwing that out there.”

I pointed out that if nothing else, it shows you’re committed.

“Yeah. The only cliché thing I’ve done, I guess, is I have a knife here,” he said, pointing to a spot near his elbow. “But, that was way long ago, before everyone started getting a knife.”

Afer a pause Sánchez elaborated (yes, he’s the type to elaborate without you having to ask — either very personable or very media savvy). “It’s been part of the renegade attitude, the whole Anthony Bourdain rebel, pirate, kind of kitchens. I came up in that. I spent time in New York before the celebrity chef train started to move.”

“It was like a punk rock thing to work in a kitchen back then, right?” I prodded. Like all good food writers, I’ve read Bourdain’s books.

“Oh yeah. Especially when I started,” Sánchez said. “You have to understand that my dream was not to be on television, my dream was to be a restaurant owner. That’s what I wanted. The television came about from that, and that became this auxiliary piece that was going to help promote my restaurants.

“That message has changed, because now it’s a cultural tool. Now, I’m teaching someone in Sioux Falls, Iowa, that doesn’t have a Latin neighborhood, necessarily, or doesn’t have access to those ingredients, but now knows how to work with a chipotle, or an ancho chile, or tomatillos. Television allows me to transmit those messages instantaneously. That’s when you use it for good, not for self-promotion and fame. You know what I mean?”

I include the italics because Aarón Sánchez always pronounces Spanish words in italics. I asked if the Bourdain thing (by which I meant, but apparently couldn’t quite bring myself to mention by name, Bourdain’s suicide) has made him more reflective, or introspective about that chef-as-pirate lifestyle they both came up in. I fumbled around the question a bit, as I do when I’m asking an unplanned question and trying not to offend my subject. Sánchez jumped in before I could stammer too much. Like I said, the guy likes to make the food writer’s job easier. Probably not a fluke that he’s on TV all the time.

“Absolutely,” he confirms. “I’ve known Tony, I knew Tony for… he wrote the book in 2000. We were hanging out three years before that. I think this was a big wake up call to all of us to have balance in our lives. I think most chefs nowadays that are starting out want to fast track it and that’s the biggest part of it.

“So, we’re trying, as chefs, to have better family connections. My hope is that this situation with Anthony does not push some chefs that are having a bad year — business is down, whatever — to go that route. I hope not. They’re thinking ‘Oh, shit. Anthony Bourdain had it all. Hot actress girlfriend, tons of money, travels the world, and he’s still depressed.’

“I really want to do what I can to address the mental health issue of chefs. I think it’s a big problem that they need to be more conscious of.”

The chef lifestyle that Bourdain wrote about seemed so sexy, because they had a code of their own, and they lived outside of the “normal,” 9-5 rat race. And maybe economic aspects of it, like having to work until 2 am and show up the next day even if you’re sick because chefs don’t get sick days, seemed, if not exotic, then certainly extreme. But nowadays, while the chef lifestyle has gotten romanticized, more and more of us have been pushed into professions that similarly require longer hours, with more tenuous job security, lower incomes, and the same “hit it big or wash out” mentality as chefs.

We compensated chefs like Aarón Sánchez with the promise of possible fame, but the underlying problems remain. Maybe Bourdain isn’t just a wake-up call for people to take care of their mental health. Maybe he’s a wake-up call for us to take better care of all our overworked, underpaid working adults.

Vince Mancini is on Twitter. More reviews here. Our statement on press trips is here.