SHOWS

Covers Books

EVENTS

FEATURED

BRANDS

TRAVEL,

DRINKS & EATS

DRINKS & EATS

Latest

A Pivotal Taco Bell Moment In Myke Towers’ Past Is At The Heart Of His New Partnership With The Restaurant

Myke Towers has become one of Latin music's biggest voices in recent years, and now he's extending his empire to restaurants. It was announced last month that he had entered into a partnership with Taco Bell. The latest product of the team-up is a new ad for the Chicken Bacon Ranch Street Chalupas, which features Towers' song "Sunblock." The collaboration actually has some personal meaning for Myke. As a press release explains, there was a day in 2015 when he was recording in Miami. All he had was $10 and no ride, so he and two friends walked to a…

Don Toliver Contributes The Spooky New Song ‘Creepin’ To The ‘Scream 7’ Soundtrack

The Scream franchise is as strong as ever: It's been three decades, and this month's Scream 7 will be the third new Scream movie in the past four years. They're getting some cool music people involved, too, as today (February 20), Don Toliver shares "Creepin'," a new song for the film. "Creepin'" is the latest of a batch of five new songs from the film debuting this month. It follows Sueco's "Rearranging Scars" and Ice Nine Kills' "Twisting The Knife" (featuring Scream 7 star Mckenna Grace), and will be followed by Jessie Murph's "Criminal" and Stella Lefty's "The Kill," both…

Summerfest’s Huge 2026 Lineup Is Led By Ed Sheeran, Post Malone, Alex Warren, And More

Milwaukee's Summerfest routinely has one of the biggest and most varied lineups in the music festival space. Organizers announced the roster for the 2026 edition today (February 19) and that remains true. The festival is set for three weekends: June 18 to 20, June 25 to 27, and July 2 to 4. Headlining are Garth Brooks; Megan Moroney; Don Toliver with SahBabii, Che, SoFayGo, sosocamo, Chase B, and Lelo; Carín León; Ed Sheeran with Myles Smith and Arron Rowe; Cody Johnson with Jessie Murph; Post Malone with Carter Faith; Muse; Alex Warren; and Jelly Roll with Tyler Hubbard. There's a…

Twenty One Pilots, Blink-182, Myles Smith, And More Lead This Weekend’s Innings Festival Lineup

Tempe, Arizona's Innings Festival occupies a unique space in the festival world thanks to its combination of music and appearances from baseball legends. The 2026 edition goes down this weekend from February 20 to 22 at Tempe Beach Park & Arts Park, and the lineup is a winner. On the music side, headlining on Friday are Mumford & Sons, and also on the lineup are Goo Goo Dolls, Myles Smith, Grouplove, Peach Pit, OK Go, Marcy Playground, Congress The Band, and Tyler Ballgame (a perfect booking, by the way). Saturday is led by Twenty One Pilots, along with Cage The…

Ed Sheeran Hops On U2’s ‘Days Of Ash,’ A Surprise EP Set To Be Followed By A New Album This Year

These days, U2 tend to take a long time between new releases, and when they do drop something, they give it a proper promotional lead-up. Not this time: Today (February 18), the legendary Irish rockers shared Days Of Ash, a six-track EP released to coincide with the Christian observance of Ash Wednesday. One of the few guests appearing on the project is Ed Sheeran, who, along with Ukrainian singer Taras Topolia, features on "Yours Eternally." Per a press release, Sheeran introduced U2 to Topolia, who wound up being the inspiration for the song, which was "written in the form of…

Taylor Swift, Morgan Wallen, And Ed Sheeran Lead The New Yearly Top Global Artists Chart

Every year, the IFPI (International Federation of the Phonographic Industry) shares its Global Artist Chart, which ranks the biggest-selling artists of the previous year. In 2024, it was Taylor Swift who topped the ranks. The latest chart is out now (as Billboard notes) and for 2025, it was once again Swift. This is Swift's sixth time topping the ranks, now having done so in 2014, 2019, 2022, 2023, 2024, and 2025. (It was BTS who interrupted her streak in both 2020 and 2021.) Rounding out the top five are Stray Kids, Drake, The Weeknd, and Bad Bunny. Other notable entries…

Mac Miller Makes A Posthumous Return On Thundercat’s Endlessly Groovy ‘She Knows Too Much’

Before Mac Miller's tragic passing in 2018, Thundercat was one of his closest collaborators. Now, Thundercat has a new album, Distracted, on the way, and it includes a new song with Mac, "She Knows Too Much." Thundercat sought and received permission from Miller's estate to complete the song and feature it on the album. In a statement, Thundercat says, "I'm grateful to have spent my time on this planet with Mac. What an artist, what a spirit, what a joy to have experienced.” Léa Esmaili, the animated video's director, also said: "First of all, making this music video is a…

The Kid Laroi Will Spend This Summer Touring North America Alongside Tommy Richman

At the top of January, The Kid Laroi helped kick off a new year of music with the release of his latest album, Before I Forget. Since then, fans have been wondering if he might tour in support of the project and now we know for sure, as today (February 17), Laroi announced the A Perfect World Tour. The shows stretch from April to November. First, there's a North American run that goes until mid-June. After some time off, that's followed by UK and European shows in October and November. The artist pre-sale begins February 18 at 10 a.m. local…

This Week’s Five Best Sneakers Drops, Featuring The Jordan 6 Infrared Salesman & More

Welcome to SNX, your weekly roundup of the best sneakers to hit the internet. It’s February 13th, and we’re barely dropping the first SNX of the year, so… what gives? Well, considering January is traditionally a quiet time for new sneaker releases — and this year was no different — we decided to sit it out and wait until the true 2026 sneaker year started, which just so happens to be this week in mid-February. As a new year in sneakers begins, we’ve decided to restructure SNX a bit — gone are the days when we highlight every single notable…

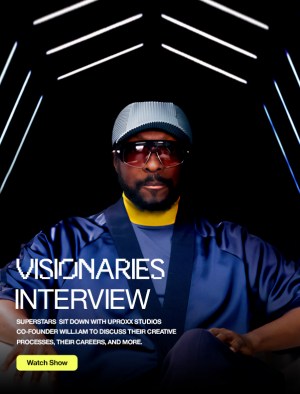

UPROXX Kicked Off NBA All-Star Weekend Right With A Celebration Of Music, Ball, And LA

The 2026 NBA All-Star Game festivities culminate on Sunday, but All-Star Weekend is about so much more than the game. Officially, the action actually kicks off tonight (February 13), most notably with the All-Star Celebrity Game and the Rising Stars games. Tomorrow, there's also the iconic 3-Point Contest, Kia Shooting Stars, and Slam Dunk Contest. There are also plenty of key events during and surrounding the big weekend. Case in point: Last night, UPROXX, Dime, and Shoe Palace teamed up for the We LA All-Star Tip-Off Party. The at-capacity event, led by UPROXX Chief Visionary Officer will.i.am., was a big…

Weezer Compiled Their Classic Color-Themed Albums Into ‘Coloring Book,’ A Clever Vinyl Box Set

If you look at Weezer's discography, there's something about it that stands out from most other bands: They have six self-titled albums. Officially, they all have the same name, Weezer, but they're also known as the Blue Album, Green Album, Red Album, White Album, Black Album, and Teal Album, based on the primary color of the art's background. Now, Weezer have spun this into a fun idea for a vinyl box set: The group just announced Coloring Book, which features the aforementioned albums pressed on appropriately colored vinyl. The set itself is also a "comprehensive book experience" with 72 illustrations…

Charli XCX And Superfan Djo Collaborate On Charli’s New ‘Wuthering Heights’ Album That’s Out Now

Djo (aka Joe Keery) is a huge Charli XCX fan. In an interview from 2022, well before the launch of the now-iconic Brat era, he said Charli was one of his idols. He told Pitchfork around the same time, "Charli's just sick. She's a great pop star." In 2024, he also said, "I just think she's really cool and doing her own thing and not afraid to be yourself, which is kind of the... that's the whole point." It was surely a thrill for him, then, when he got to present alongside her at the Golden Globes back in January.…

Johnny Blue Skies Enters His Dance Era On A Newly Announced Album, ‘Mutiny After Midnight’

2024 saw the release of Passage du Desir, the debut album attributed to Johnny Blue Skies, an alter-ego of Sturgill Simpson. Now, he's going all in on the moniker: A new press release doesn't even mention Simpson's real name. As for the purpose of that release, today (February 13), the band Johnny Blue Skies & The Dark Clouds has announced Mutiny After Midnight, a new album. The project sees Simpson/Johnny Blue Skies return to Atlantic for his first time since 2016's A Sailor's Guide To Earth. In a statement, Johnny Blue Skies says of the label relationship and of the…

Dua Lipa Lends Her Vocals To Danny L Harle’s Thumping ‘Two Hearts’

Danny L Harle has mostly been in producer mode in recent years, but today (February 13), he has a new album of his own, Cereulean, out now. He called upon some of his big-shot friends to make it happen, including Dua Lipa, who sings on "Two Hearts." The track isn't too far out of Lipa's dance wheelhouse, but it's more clubby and electronic than she tends to lean in her own work. In a 2024 interview, Harle spoke about working with Dua on her album Radical Optimism, saying: "It’s indescribable to hear her sing in the room. I had the…

Cardi B Gave A Bunch Of Songs Their Live Debut To Launch The ‘Little Miss Drama Tour’

For as big as Cardi B is, she actually hasn't done a ton of touring. There was a run of arena shows in 2019 but that's it. That changed last night (February 11), though, when she kicked off the Little Miss Drama Tour in Thousand Palms, California. The setlist (via setlist.fm) overwhelmingly pulled from Cardi's new album Am I The Drama?, with 21 of the 37 songs performed coming from the project. A bunch of the album tracks, naturally, were performed live for the first time here. Other big hits from throughout her career, both her own songs like "WAP"…

Tame Impala Is Going On Tour And Taking Djo And Dominic Fike With Him

Back in September, Joe Keery, known musically as Djo, starred in Tame Impala's video for "Loser." Keery and Kevin Parker seem to have hit it off, as today (February 12), Tame Impala announced a run of North American tour dates, some of which will feature Djo as the opener. For the other ones, Dominic Fike is opening. The shows run from July to September. There will be various pre-sales starting February 18 at noon local time, while the public on-sale starts February 20 at noon local time. More information can be found on the Tame Impala website. Check out the…

‘Erupcja’: Everything To Know About Yet Another New Movie Starring Charli XCX

As Charli XCX was in the midst of her culture-defining Brat summer in 2024, she was also working on a secret movie. It didn't really stay secret for long, though, as word about Erupcja (the title being the Polish word for "eruption") quickly got out during filming. Erupcja is just the latest entry in Charli's quickly expanding filmography. In just 2025 and 2026, she appears in 100 Nights Of Hero, I Want Your Sex, The Gallerist, Faces Of Death, and of course, The Moment. Ahead of the movie's debut, keep reading for everything you need to know. Plot An official…

SA-RA Creative Partners Continue A Packed 2026 With The Throwback Soul Of ‘It’s Better With You (Forever With You)’

You've heard Sa-Ra Creative Partners -- the trio of Taz Arnold, Shafiq Husayn and Om'Mas Keith -- before. They and/or the group's members individually have collaborated with everybody from Jurassic 5 to Dr. Dre to Jay-Z. Keith also has a Grammy win in the Best Urban Contemporary Album category, for his work on Frank Ocean's iconic Channel Orange. That said, in terms of their own albums, it's been a while since that's been a focus. So far, they have two LPs to their name: 2007's The Hollywood Recordings and 2009's Nuclear Evolution: The Age Of Love. That's about to change,…

Jack Harlow Is Launching A New Era Soon As He Announces ‘Monica,’ An Album

The latest album news from Jack Harlow wasn't even his own: Back in June, Lorde said that Harlow had heard her album Virgin and told her of her lyrics, "These are bars!" She did note, though, that they met at New York's iconic Electric Lady Studios, where Harlow was working on new music. Soon, we'll get to hear it, as today (February 10), Harlow announced that a new album called Monica is coming on March 13. A press release notes the project was written over the past year at Electric Lady, and that the project was created followed Harlow's move…

Muna Finally Announce A New Album And Share ‘Possibly Our Favorite Song We’ve Made’

We're coming up on four years since Muna released their latest project, the self-titled album from the summer of 2022. At long last, though, they're coming back, as today (February 10), they announced Dancing On The Wall, a new album. They've also shared the title track, alongside a video. The song is extremely punchy and catchy synth-pop. In a statement, Muna says of the single: "Dancing On The Wall is possibly our favorite song we’ve made as a band. We think it’s all the best parts of MUNA -- it’s coming from a really emotional and lonely place, but the…

Stop At The Red Light For LA’s Best New Japanese Culinary Experience.

Hollywood has always been a culinary hotbed, but some of the best bites in town are tucked away and seldom spoken of. It's truly an IYKYK scene. Thankfully, we've found another of the city's best and brightest gems hiding in plain sight. Nestled directly next to Sunset Sound, where legends have etched their energies into Los Angeles' musical history for more than half a century, another kind of artistry is unfolding in the form of two restaurants housed in one building, each devoted to a different expression of craft. This is Udatsu and Rokusho, a dual establishment that shares an…

King Of Kentucky Debuts Three New Bourbons — Here’s Our Review

The King (of Kentucky) is back! Hot on the heels of landing at the number two spot on the UPROXX "Best Bourbons of 2025" list, King of Kentucky is maintaining the momentum by debuting a brand-new small-batch version of its critically acclaimed single-barrel bourbon. New for 2026, King of Kentucky Small-Batch Bourbon is a single blend of Brown-Forman bourbon, bottled at three different proof points to deliver notably different results. Batch 1 is bottled at 105 proof, Batch 2 at 107.5 proof, and Batch 3 at 110 proof. Each batch features a blend of barrels aged 12-18 years, delivering a…

Geese Continue Their Superlative Run With A Fantastic NPR Tiny Desk Concert

Back in December 2025, Geese stopped by the NPR offices to film an installment of the beloved Tiny Desk Concert series. Now, today (February 10), the performance has finally been shared. As they tend to do, Geese messed with the arrangements a little is they played their three-song set of "Husbands," "Cobra," and "Half Real." Cameron Winter also had some fun with the gathered audience between songs, joking, "Is this a ticketed thing or is this...? How do you guys get into this? I thought it was just NPR staffers here, I don't know... and friends. NPR staffers don't have…

‘The Rise Of The Red Hot Chili Peppers’: Everything To Know About Netflix’s New RHCP Documentary

The current Red Hot Chili Peppers lineup of Anthony Kiedis, Flea, Chad Smith, and John Frusciante is the longest-running iteration and the one fans know best. Over the years, though, the group has had a ton of personnel changes. One of the most notable members from the group's early era is Hillel Slovak, who joined the band shortly after it was founded. Save for a brief hiatus, Slovak was with the band from 1982 to 1988. In '88, he tragically died of a heroin overdose. Now, Slovak's story and impact is being honored in a new Netflix documentary, The Rise…